Alien Life May Require Rare 'Just-Right' Asteroid Belts

Asteroid belts similar to the one between Mars and Jupiter appear to be rare beyond our solar system, implying that complex alien life may be rare as well, a new study reports.

Fewer than 4 percent of known alien solar systems are likely to have an asteroid belt like the one in our own neck of the woods, researchers found. Belts that look like ours may help spur the evolution of life, seeding rocky planets with water and complex chemicals but not pummeling the worlds with a constant barrage of violent impacts.

"Our study shows that only a tiny fraction of planetary systems observed to date seem to have giant planets in the right location to produce an asteroid belt of the appropriate size, offering the potential for life on a nearby rocky planet," study lead author Rebecca Martin, of the University of Colorado in Boulder, said in a statement. "Our study suggests that our solar system may be rather special."

Asteroids: friends and foes

Most people regard asteroids as a threat to life. After all, a 6-mile-wide (10 kilometers) space rock is thought to have wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago here on Earth. [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

But asteroid impacts may have helped life get a foothold on our planet as well, scientists say.

For example, space rocks and comets likely delivered huge loads of water and organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — to the early Earth. And the theory of punctuated equilibrium suggests that occasional impacts could have helped accelerate the rate of biological evolution by disrupting the status quo and opening up new niches.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A just-right asteroid belt may thus be key to the evolution of complex lifeforms on rocky worlds, researchers said. And that may bad news for those of us who hope to make contact with intelligent aliens someday.

A giant planet in the right place

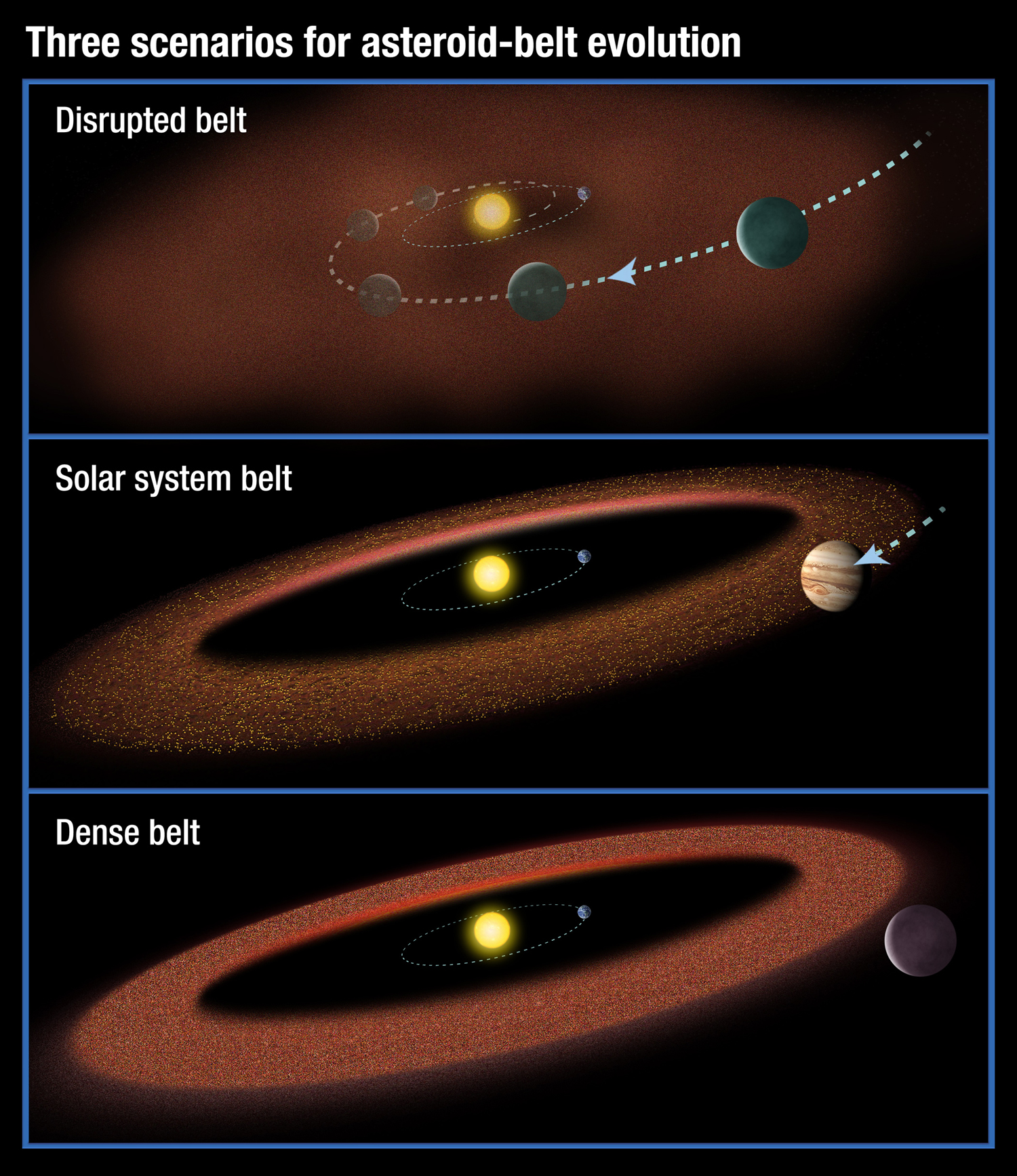

Our solar system's asteroid belt formed where it did because Jupiter's powerful gravitational pull prevented the material in the region from glomming together to create a planet. And the belt looks as it does today because Jupiter moved just the right amount long ago, researchers said.

"To have such ideal conditions you need a giant planet like Jupiter that is just outside the asteroid belt [and] that migrated a little bit, but not through the belt," said study co-author Mario Livio of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

"If a large planet like Jupiter migrates through the belt, it would scatter the material," Livio added. "If, on the other hand, a large planet did not migrate at all, that, too, is not good because the asteroid belt would be too massive. There would be so much bombardment from asteroids that life may never evolve."

Our own asteroid belt is found near the solar system's "snow line," the point beyond which it's cold enough for volatile substances such as water ice to stay intact. So Martin and Livio reasoned that alien belts are likely to be found near their systems' snow lines as well.

Using computer models, the duo calculated where the snow line should be in planet-forming disks around young stars. They confirmed their calculations using observations from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, which showed the presence of warm dust — a possible asteroid belt indicator — in about the right place around 90 such stars.

"The warm dust falls right onto our calculated snow lines, so the observations are consistent with our predictions," Martin said.

Moving inside the snow line

The researchers then studied observations of the 520 giant planets that have been found beyond our solar system to date. They determined that just 19 of them — or about 4 percent — reside outside the snow line.

The find suggests that the vast majority of Jupiter-like planets have migrated inward too much to support the existence of an asteroid belt like the one we're used to, reseachers said.. Such big moves would likely have disrupted any nascent belts, sending space rocks scattering this way and that. "Based on our scenario, we should concentrate our efforts to look for complex life in systems that have a giant planet outside of the snow line," Livio said.

The study was published Thursday (Nov. 1) in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.