The 6 strangest presidential elections in US history

Political news would have you thinking the 2016 presidential election was the nastiest, most contentious and most important our nation ever faced. However, in the annals of American elections, that one barely registers at least for sheer strangeness.

In fact, electoral politics have always been a down-and-dirty business, starting at least as early as 1800, when our founding fathers proved themselves adept at bitter battles. Other elections have featured nasty accusations, bizarre happenstance and even the death of one of the candidates.

Read on for six of the strangest presidential elections in U.S. history.

An unexpected upset, 2016

The full history of the 2016 presidential election has yet to be written, but it seems pretty certain to be one for the history books.

First, there was the raucous primary season, in which 17 Republican candidates vied on a crowded stage for the nomination, the largest presidential primary field in U.S. history. Former reality-TV star and real estate mogul Donald Trump dominated headlines from the beginning, often with Tweets and statements that seemed outright bizarre. He insinuated that fellow Republican Ted Cruz's father might have had something to do with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and at one point defended the size of his penis in a debate. Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, presumptive nominee Hillary Clinton faced an unexpected challenge from Vermont senator Bernie Sanders.

Things did not get less weird after Trump and Clinton clinched their nominations. Clinton struggled against questions about her use of a private email server during her time as Secretary of State. The issue seemed settled in July when the Federal Bureau of Investigation recommended against criminal charges, but reared its head again less than two weeks before the election when the FBI announced that it was reviewing potentially new evidence found on the computer of Anthony Weiner, the husband of Clinton's close aide Huma Abedin, during an investigation into whether Weiner had been sexting an underage girl. Yes, it almost makes that Andrew Jackson-John Quincy Adams contest look like a walk in the park, huh? Just two days before the election, the FBI cleared Clinton again.

Meanwhile, Trump refused to release his tax returns during the campaign, something that every candidate since Gerald Ford has done as a matter of course. He was widely criticized for racist remarks, such as questioning whether the "Mexican" judge in charge of his fraud case (oh, there's a fraud case — a presidential first) could be impartial. (The judge was an American citizen of Mexican heritage.)

The wildest bombshell of all came in early October, when a tape surfaced of Trump having a vulgar discussion about grabbing women by their private parts and trying to seduce a married woman. Leading up to the election, the polls were variable, but most pundits expected a clean Clinton victory. Instead, as election night ticked on, the electoral votes piled up for Trump. He ended up taking 290 electoral votes to Clinton's 232, winning the presidency. But in a final twist, the popular vote tally went to Clinton, only the fifth time in U.S. history the electoral and popular votes haven't matched.

The very first one, 1788-1789

But let's go back now to the first presidential election in our nation's history, which was one-of-a-kind in that it was literally no contest. Organized political parties had yet to form, and George Washington ran unopposed. His victory is the only one in the nation's history to feature 100 percent of the Electoral College vote. [Quiz: Weirdest Presidential Elections]

The real question in 1788 was who would become vice president. At the time, this office was awarded to the runner-up in the electoral vote (each elector cast two votes to ensure there would be a runner-up.) Eleven candidates made a play for the vice-presidency, but John Adams came out on top.

It's a tie, 1800

Electoral politics got serious in 1800. Forget the hand-holding peace of George Washington's first run — political parties were in full swing by this time, and they battled over high-stakes issues (taxes, states' rights and foreign policy alignments). Thomas Jefferson ran as the Democratic-Republican candidate and John Adams as the Federalist.

At the time, states got to pick their own election days, so voting ran from April to October (and you thought waiting for the West Coast polls to close was frustrating). Because of the complicated "pick two" voting structure in the Electoral College, the election ended up a tie between Jefferson and his vice-presidential pick, Aaron Burr. One South Carolina delegate was supposed to give one of his votes on another candidate, so as to arrange for Jefferson to win and Burr to come in second. The plan somehow went wrong, and both men ended up with 73 electoral votes.

That sent the tie-breaking vote to the House of Representatives, not all of whom were on board with a Jefferson presidency and Burr vice-presidency. Seven tense days of voting followed, but Jefferson finally pulled ahead of Burr. The drama triggered the passage of the 12th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which stipulates that the Electoral College pick the president and vice-president separately, doing away with the runner-up complications.

Things get nasty, 1828

Anything involving dueling war veteran Andrew Jackson was liable to get dirty, but the 1828 electoral battle between Jackson and John Quincy Adams took the cake for mud slinging. Jackson had lost out to Adams in 1824 after Speaker of the House Henry Clay cast a tie-breaking vote. When Adams chose Clay as his Secretary of State, Jackson was furious and accused the two of a "corrupt bargain."

And that was before the 1828 election even got started, when Adams was accused of pimping out an American girl to a Russian Czar. Jackson's wife, Rachel, was called a "convicted adulteress," because she had, years earlier, married Jackson before finalizing her divorce to her previous husband. Rachel died after Jackson won the election, but before his inauguration; at her funeral, Jackson blamed his opponents' bigamy accusations. "May God Almighty forgiver her murderers, as I know she forgave them," Jackson said. "I never can." [6 Most Tragic Love Stories in History]

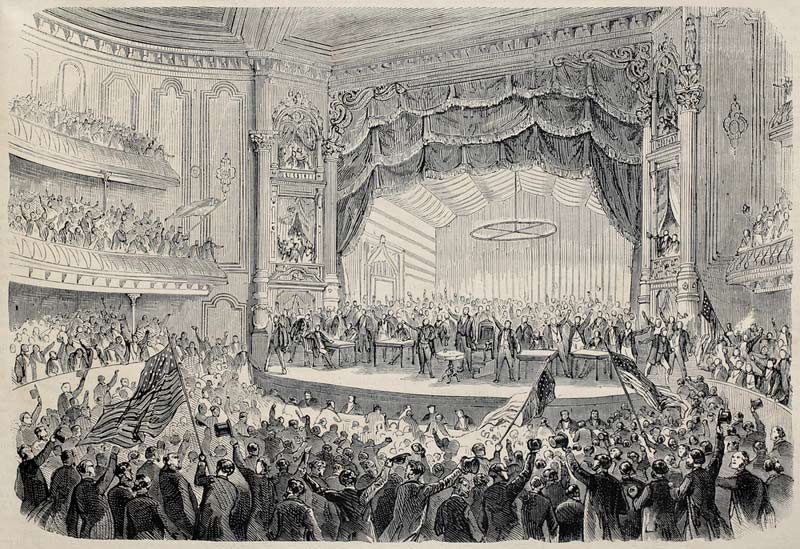

To round out a rough election, Jackson's inauguration party (open to the public) turned into a mob scene, with thousands of well-wishers crowding into the White House.

"Ladies fainted, men were seen with bloody noses, and such a scene of confusion took place as is impossible to describe," wrote Margaret Smith, a Washington socialite who attended the party.

Running against a corpse, 1872

In 1872, incumbent Ulysses S. Grant had an easy run for a second term — because his opponent died before the final votes were cast.

Grant had the election in the bag even before his opponent, Horace Greeley, died, however. The incumbent won 286 electoral votes compared with Greeley's 66 after election day. But on Nov. 29, 1872, before the Electoral College votes were in, Greeley died and his electoral votes were split among other candidates. Greeley remains the only presidential candidate to die before the election was finalized.

The hanging chads, 2000

Democrat Al Gore beat Republican George W. Bush in the popular vote in the 2000 election, but the electoral vote was a close, and controversial, call. As election night drew to a close, New Mexico, Oregon and Florida remained too close to call.

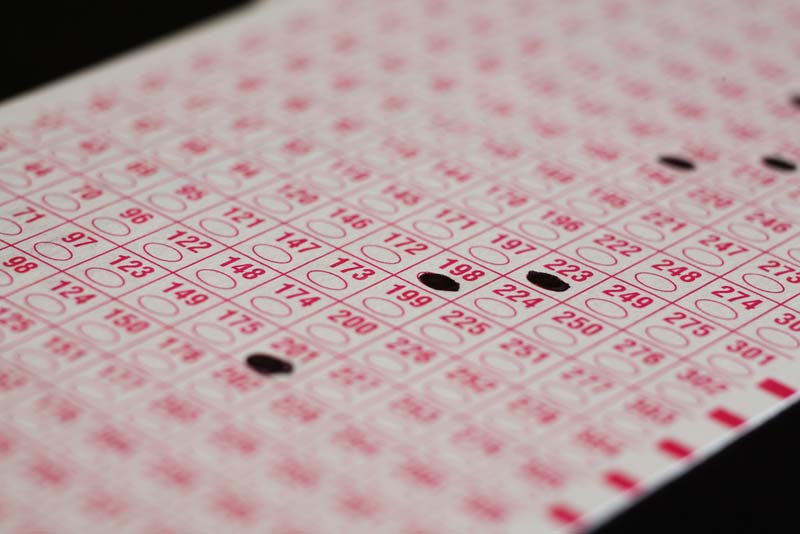

It would be Florida that determined the winner, but not until the Supreme Court weighed in. For a month, the outcome of the election remained in recount limbo, as Gore's campaign contested the vote count in several close counties and the Florida and U.S. Supreme Courts engaged in a tug-of-war over whether to halt the recounts or extend their deadlines. Among the challenges faced by the hand counts: determining whether semi-attached scraps of paper, or "hanging chads," on punch-card ballots should count as votes.

Ultimately, on Dec. 12, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that a statewide recount was unconstitutional, alongside a further decision that the smaller recounts could not go forward. The decision meant the original vote counts stood, giving the election to Bush.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Archaeologists may have discovered the birthplace of Alexander the Great's grandmother

Elusive neutrinos' mass just got halved — and it could mean physicists are close to solving a major cosmic mystery