Why Hurricane Sandy Hit Staten Island So Hard

Staten Island drew a very bad hand during Hurricane Sandy.

The island, one of the five boroughs of New York City, was the victim not only of geography — it sits at the back of New York Harbor — but of the unfortunate coincidence of Hurricane Sandy's arrival and high tide.

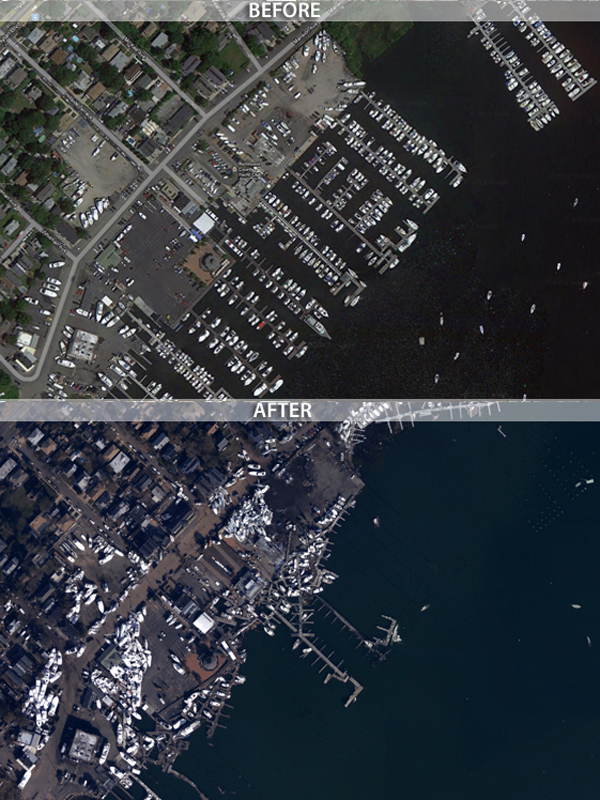

The storm led to massive flooding and extensive damage along Staten Island's coastal areas. Neighborhoods there are still struggling to clean up flood damage and restore power.

Peak storm tides at Staten Island reached 16 feet (5 meters); by the same measure, waters at Manhattan's Battery Park reached only 11.1 feet (3.4 m). [On the Ground: Hurricane Sandy in Images]

Along the northeastern coast of Staten Island, the area of the city with the most casualties, monitors recorded storm tide fluctuations of 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m) every 30 seconds, perhaps indicating that large waves repeatedly slammed into the shoreline as the storm peaked.

"It was geographic circumstance more than anything else," said Andrew Ashton, a coastal geomorphologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. "Staten Island is at the end of, basically, a big funnel between New Jersey and New York."

Funneling the surge

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Staten Island sits right in the crook of the New York Bight, the slight indentation in the Atlantic coastline from the northeastern tip of Long Island to southern New Jersey. The bight forms a sharp angle at Staten Island, which means the island, along with adjacent segments of New Jersey and Long Island, bears the brunt of surging storm waters.

"A storm surge is just a very large wave that moves ahead of a storm," Ashton told OurAmazingPlanet. "As it moves toward the coast, the pieces of land squeeze it from the sides and the wave becomes taller."

Much of Hurricane Sandy's storm surge was funneled through Raritan Bay, between southeastern Staten Island and New Jersey, as the storm made its way toward the Atlantic coast. Combined with the strong winds, the storm surge kept waters from receding during low tide as they normally would.

"Once the surge reaches the New York Bight, there's nowhere else for the water to go, and it piles up," said Jeff Donnelly, a Woods Hole sedimentary geologist.

A changed landscape

Even though storm and hydrologic models forecast massive flooding on Staten Island, there was little that residents could have done ahead of Sandy to avoid the flooding and other damage, experts say.

Part of the problem was that residential areas had expanded into the island's natural wetlands, something that has occurred in other coastal cities as well.

"Naturally there were more coastal wetlands that provided a buffer between the storm waves and the coast. But to get more land, these cities have expanded greatly and filled in a lot of historic wetlands," Donnelly said.

Staten Island weathered some hard hits in the past, Donnelly said, including the 1893 New York hurricane and the 1821 Norfolk and Long Island hurricane, which may have packed a surge even larger than Sandy's.

But changes on Staten Island, combined with a 1.5-foot (0.5 m) rise in sea level since 1821, have made the borough more open to disaster since then, he said.

"In the last 200 years, we've built cities on barrier islands and wetlands, more people are living on the beach, and sea level is rising." Donnelly said. "We're much more vulnerable than we were almost 200 years ago."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook & Google+.