Sandy's Storm Surge Mapped - Before It Hit

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — In June, William Fritz and his colleagues developed a model showing how New York's geography would amplify a storm surge in the event of a large storm, spelling trouble for low-lying urban areas.

Then came Hurricane Sandy.

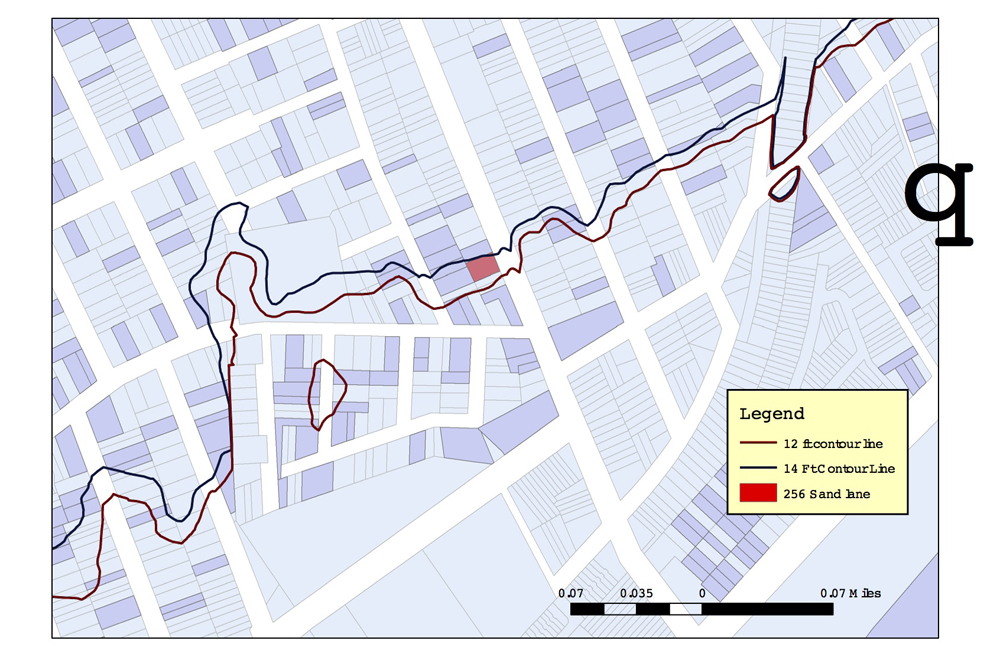

"The storm surge happened almost exactly as we modeled it," said Fritz, a geologist at the College of Staten Island, where he's also the interim president. The only difference: Sandy's surge was slightly larger than the model predicted, topping out at 14 feet (4.3 meters) instead of the 12 feet (3.7 m) the model showed.

But that's a small difference in terms of the damage wrought. Fritz's colleague Alan Benimoff mapped the storm surge on Staten Island by looking at the extent of washed-up debris. The point where Benimoff reported storm-tossed flotsam was only slightly farther than the model predicted — the width of one house, he said. [History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

The authors presented their model here yesterday (Nov. 6) at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America.

Lessons learned

There are several lessons to be learned from their model, and the experience of Sandy, Fritz told OurAmazingPlanet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, "we need to protect the dunes and marshes that we still have," he said. The hardest hit area of the island used to be a marsh, he added.

Second, it may make sense to rebuild and re-establish these natural "sponges." And finally, it simply doesn't make sense to build apartments and houses in low-lying areas, because they will flood, Fritz said.

"We need to look at rezoning these areas, and using them for parks and day-use areas," he said.

If dunes and marshes that used to line Staten Island and elsewhere still existed, they could have slowed encroaching waters and allowed people more time to get out of their homes, Fritz said. Instead, flooding occurred in a matter of minutes or even seconds, surprising some people sheltering in their basements, he said.

"What was once a dune has long since been paved over, and water flooded down into the old marsh," he said.

Staten Island hit hard

Hurricane Sandy hit Staten Island hard, with about half of the deaths that occurred in New York City happening there. The storm claimed the lives of one student at the College of Staten Island and a faculty member's wife, Fritz said.

The geography of the New York City area makes it very vulnerable to storm surges. The coasts of Long Island and New Jersey meet at a 120-degree angle, perfect for concentrating the surge and sending it directly toward Staten Island, Fritz said. From here, the water flows into New York Harbor, but it has nowhere to go except inland, thanks to water moving south from the Long Island Sound through the East River. The Sound, angled to the northeast, accentuates the storm surge as winds from the northeast (typical of hurricane and extra-tropical cyclones) pile up water and send it toward New York City, Fritz said.

"Most people don't think, or didn't think, of New York City as being in the hurricane belt," he said. Hopefully that will change, he said: "My message is that we need urban planning to account for flooding. People should make no mistakes that hurricanes will come again."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.