Pristine Moon Crater Could Help Unlock Impacts' Secrets

Scientists trying to understand the evolution of impact craters on Earth and other rocky bodies have found a good case study on the moon.

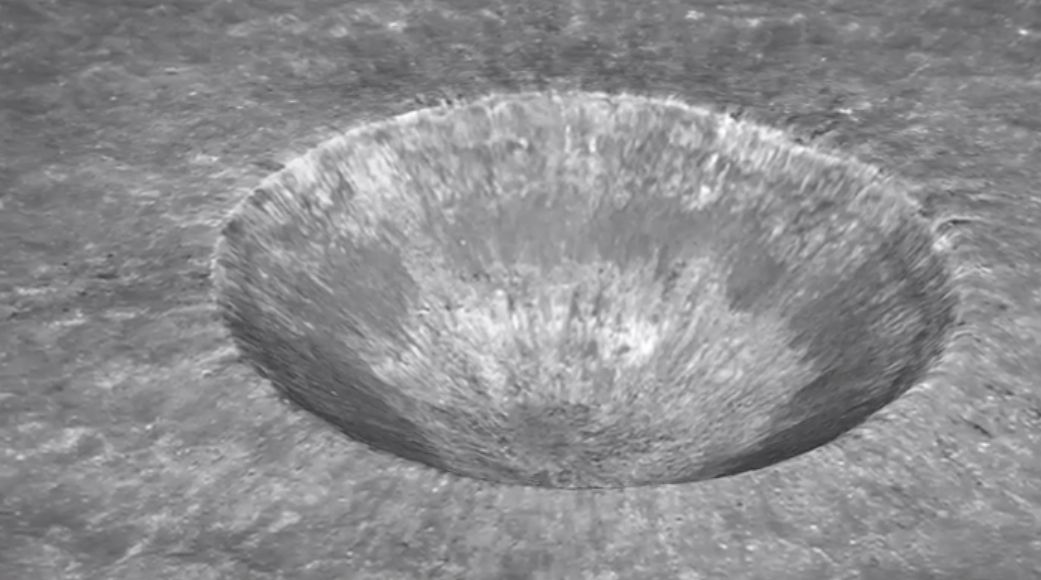

Researchers are focusing on Linne Crater, which lies in the moon's Mare Serenitatis region. Linne is just 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometers) wide, but it's extremely young — having formed just 10 million years or so ago — and beautifully preserved.

Craters don't erode nearly as quickly on the moon as they do on Earth, where wind and water reshape and fill in craters at a rapid clip. But Linne is pristine even for a lunar crater, researchers said; it shows no signs of any subsequent major impacts, retaining its original shape more or less intact.

And that shape is a bit of surprise. Scientists had thought simple lunar craters such as Linne should be bowl-shaped. But observations by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft (LRO) show that Linne is actually an inverted cone.

Linne's shape and the way rocks are scattered around its rim could help shed light on how craters start out on Earth and Mars, and how weathering wears them down, a new NASA video explains.

"Without craters like Linne on the moon, we wouldn't know how landforms evolve over time in the presence of weather, climate change and other factors," the video's narrator says.

NASA launched the $504 million Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in June 2009 to map the moon in unprecedented detail with seven different instruments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The spacecraft, which is about the size of a small car, is studying the lunar surface for scientific and exploration purposes. Its maps will help researchers identify safe landing sites for future human missions, assess lunar resources such as water ice and better understand how the moon's radiation environment may affect humans, NASA officials say.

LRO has already gathered as much data as all other planetary missions combined, officials say.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.