A 300-year-old, leather-bound instruction manual contains some of the earliest examples of attempts to teach the deaf to communicate.

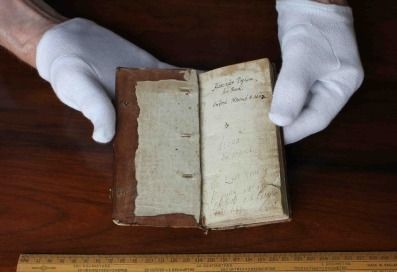

The manual belonged to Alexander Popham, a deaf teenager from a noble English family who was taught to speak in the 1660s. The leather-bound notebook was discovered in 2008 at a stately English manor called Littlecote House.

The finding suggests that one of the boy's tutors, John Wallis, was a few hundred years ahead of his time in understanding that deaf people needed their own language to communicate, said linguist David Cram of the University of Oxford.

Cram is presenting his findings at a Royal Society lecture Nov. 9 in London.

Wallis also likely made use of a rudimentary method of sign language, Cram said.

"Wallis made the point that in order to teach a deaf person our language, the language of the hearing, we had to learn their language," Cram told LiveScience. "He certainly would have made use of sign language and also of a writing system."

At the time, men who were mute were deemed incompetent and not allowed to inherit property or make wills.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The tradition going back to the Middle Ages was that deafness and dumbness went together," Cram said. "If you couldn't teach people to speak, you wouldn't be able to teach them to communicate."

In order to preserve young Popham's social status, his family asked two Renaissance Men of the period, Wallis and William Holder, to teach him to speak.

Amazingly, Popham learned to communicate and speak (although historical records don't reveal how well), became a minor celebrity of the era and was even presented at court, Cram said. He eventually married the daughter of one of the leading intellectual women of the 17th century.

In later years, Wallis and Holder disputed who should get credit for teaching Popham to speak. While Holder was the first to tutor Popham and may have first coaxed the boy to say words, there's no doubt that Wallis was the one who taught Popham to use those words to communicate, Cram said.

"It's not clear that Holder was doing anything more than trying to get someone to produce words parrot-fashion," Cram said.

After Holder left his job as Popham's tutor, Wallis took his place.

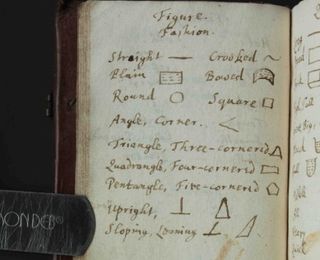

The small, leather-bound manual written by Wallis reveals that he understood that deaf people could communicate and that speaking was separate from communicating — in other words, being able to produce sounds doesn't mean you can make yourself understood. Nor is speech the only way to communicate. The book contains detailed explanations of vocal articulation, but also figures and signs and exercises in phonetics, syntax and sentence construction.

"Wallis made the point that a really profoundly deaf person will need to be taught to communicate before they articulate," he said.

Wallis wasn't the first person to experiment with signs. Hundreds of years earlier, Benedictine monks who took a vow of silence also developed their own primitive sign language, which formed the basis of later attempts in Spain to teach the deaf to sign, Cram said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.