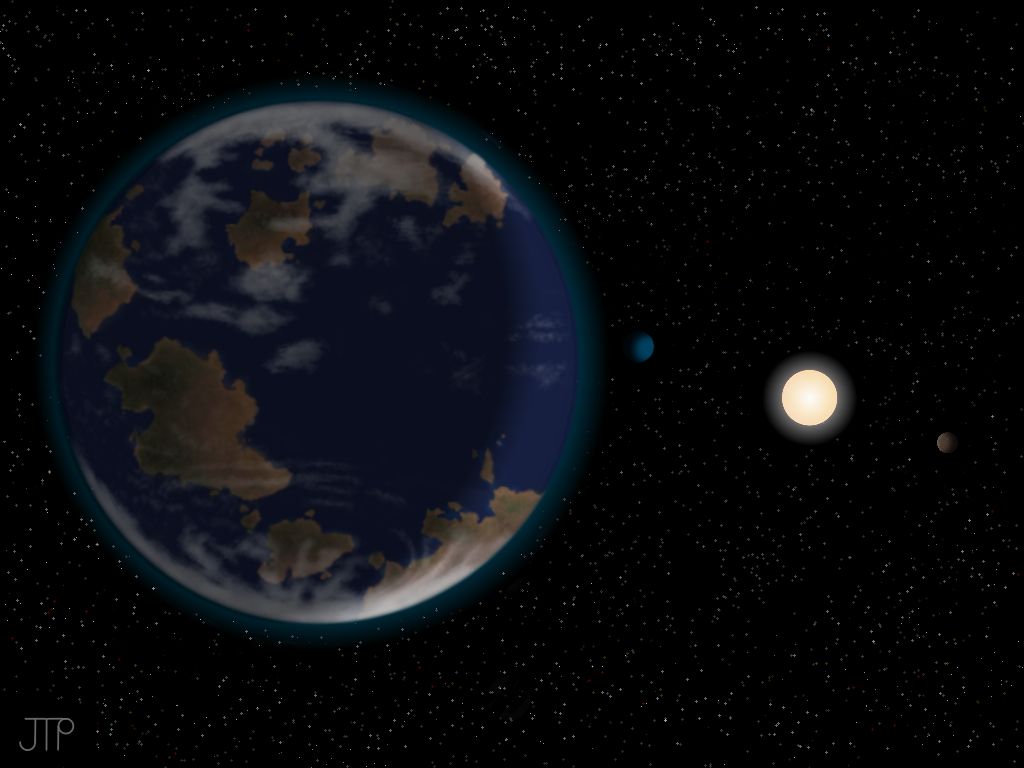

Astronomers have detected an alien planet that may be capable of supporting life as we know it — and it's just a stone's throw from Earth in the cosmic scheme of things.

The newfound exoplanet, a so-called "super-Earth" called HD 40307g, is located inside its host star's habitable zone, a just-right range of distances where liquid water may exist on a world's surface. And the planet lies a mere 42 light-years away from Earth, meaning that future telescopes might be able to image it directly, researchers said.

"The longer orbit of the new planet means that its climate and atmosphere may be just right to support life," study co-author Hugh Jones, of the University of Hertfordshire in England, said in a statement. "Just as Goldilocks liked her porridge to be neither too hot nor too cold but just right, this planet or indeed any moons that it has lie in an orbit comparable to Earth, increasing the probability of it being habitable."

HD 40307g is one of three newly discovered worlds around the parent star, which was already known to host three planets. The finds thus boost the star's total planetary population to six. [Video: Super Earth May Have Liquid Water]

Finding new signals in the data

The star HD 40307 is slightly smaller and less luminous than our own sun. Astronomers had previously detected three super-Earths — planets a bit more massive than our own — around the star, all of them in orbits too close-in to support liquid water.

In the new study, the research team re-analyzed observations of the HD 40307 system made by an instrument called the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher, or HARPS.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

HARPS is part of the European Southern Observatory's 11.8-foot (3.6 meters) telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. The instrument allows astronomers to pick up the tiny gravitational wobbles an orbiting planet induces in its parent star.

The researchers' new analysis techniques enabled them to spot three more super-Earths around the star, including HD 40307g, which is thought to be at least seven times as massive as our home planet.

HD 40307g may or may not be a rocky planet like Earth, said study lead author Mikko Tuomi, also of the University of Hertfordshire.

"If I had to guess, I would say 50-50," Tuomi told SPACE.com via email. "But the truth at the moment is that we simply do not know whether the planet is a large Earth or a small, warm Neptune without a solid surface."

A jam-packed extrasolar system

HD 40307g is the outermost of the system's six planets, orbiting at an average distance of 56 million miles (90 million kilometers) from the star. (For comparison, Earth zips around the sun from about 93 million miles, or 150 million km, away.)

The other two newfound exoplanets are probably too hot to support life as we know it, researchers said. But HD 40307g — which officially remains a "planet candidate" pending confirmation by follow-up studies — sits comfortably in the middle of the star's habitable zone.

Further, HD 40307g's orbit is distant enough that the planet likely isn't tidally locked to the star like the moon is to Earth, researchers said. Rather, HD 40307g probably rotates freely just like our planet does, showing each side of itself to the star in due course.

The lack of tidal locking "increases its chances of actually having Earth-like conditions," Tuomi said.

The new study has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

A candidate for direct observation

Super-Earths have been spotted in other stars' habitable zones before. For example, a team using NASA's prolific Kepler Space Telescope announced the discovery of the potentially habitable world Kepler-22b in December 2011.

Kepler-22b lies 600 light-years away, which is not terribly far considering that our Milky Way galaxy is about 100,000 light-years wide. But HD 40307g is just 42 light-years from us — close enough that future instruments may be able to image it directly, scientists say.

"Discoveries like this are really exciting, and such systems will be natural targets for the next generation of large telescopes, both on the ground and in space," David Pinfield of the University of Hertfordshire, who was not involved in the new study, said in a statement.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.