Kilimanjaro Ice Field Shrinks and Splits

Another ominous sign that Mount Kilimanjaro's ice fields may disappear in 50 years has emerged.

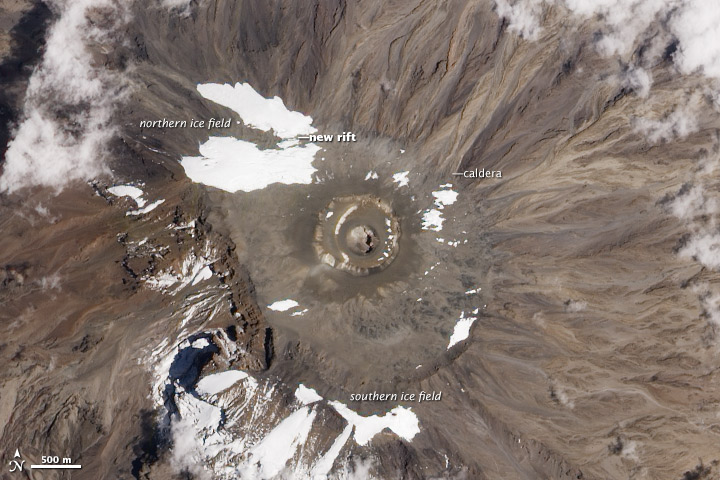

What was once the largest remaining ice field on Kilimanjaro shrank and separated into two pieces, a research expedition discovered in September. The summit's northern ice field now has a rift large enough to ride a bike through, Kimberly Casey, a glaciologist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, told NASA's Earth Observatory.

The gap is visible in an image acquired by the Advanced Land Imager on NASA's Earth Observing-1 satellite on Oct. 26 and in panoramic images Casey captured during the research expedition.

Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania, is Africa's highest peak — 19,341 feet (5,895 meters) — and harbors three distinct ice fields: One on its western slope and two within the summit plateau. The northern ice field first started developing a hole in 1970.

The ice cover on the volcano's western slopes will disappear by 2020, and the ice fields in the plateau will be gone by 2040, predicts a study in the Oct. 1 issue of the journal Cryosphere Discuss. Scientists generally agree the ice fields will disappear completely by 2060 if climatic conditions continue unchanged.

The major cause of the ice loss is a matter of debate. An increasingly dry atmosphere in the region, which leads to less snowfall, plays an important role, studies show. On the other hand, additional research confirms that a warming climate also contributes to the disappearing ice.

Surveys of Kilimanjaro's ice fields a century ago found nearly 8 square miles (about 20 square kilometers) of ice. By 2003, the ice was down to 0.97 square miles (2.51 square km), and on June 17, 2011, the ice covered 0.68 square miles (1.76 square km).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.