How Eminem Invents Freestyle Rhymes on the Spot

Freestyle rappers such as Eminem and Philadelphia's Cassidy make up and bust out rhymes on the spot — a hugely challenging art form. Now, however, researchers have learned how the brain does it.

A new study finds that when rappers improvise, parts of their brains linked to motivation, organization and integration get active, while portions responsible for self-monitoring and control get quiet. The findings suggest freestyle rappers essentially shut down the parts of their brains that might disrupt their creative flow.

"If an athlete starts paying attention to what they're doing, how they're going to move their body to catch a ball, they'll clutch and they won't do it," said study researcher Allen Braun, the chief of the language section of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), a part of the National Institutes of Health. Freestyle rappers may face a similar challenge when making up rhymes, Braun told LiveScience.

"You have to suspend that kind of attention," he said.

The improvising brain

Braun and his colleagues are interested in how the brain thinks creatively. To find out, they've previously researched the improvisation of music; now, they've turned their focus to the intersection of music and language in the brain. They teamed up with two freestyle artists, Michael Eagle and Daniel Rizik-Baer, to investigate. [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

Eagle and Rizik-Baer helped the researchers publicize their study in the Washington, D.C., and Baltimore freestyle communities, eventually recruiting 12 male freestyle rappers to come drop rhymes while in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine. The machine measures oxygen levels in the brain, providing a map of blood flow that indicates which areas of the brain are active and which are at rest at any given time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The rappers were all given an eight-measure (or –bar) backing track and a set of lyrics to memorize. After they rapped those lyrics in the fMRI scanner, they were given the same eight bars of music and told to freestyle about whatever they liked.

"They talked a lot about their environment, about how they are in the scanner," said study researcher Siyuan Liu, a scientist at the NIDCD. "Or sometimes they talked about their careers, like how many albums they'd published."

Freestyle flow

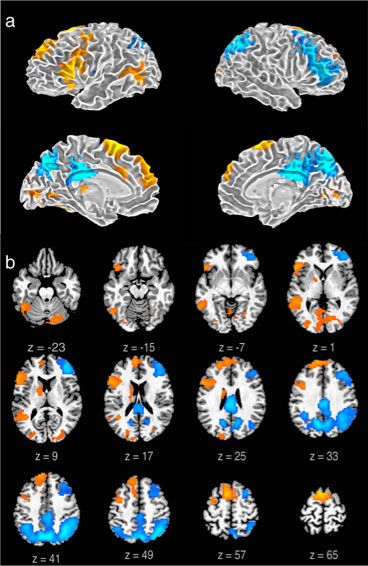

Whatever the subject, the rappers' brains activated differently during the improvised flow versus the memorized lyrics. The medial prefrontal cortex became more active during the freestyle rap, while the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex became less active. Both of these regions are in the front of the brain, behind the forehead, with the medial prefrontal cortex sitting more toward the center of the brain than the dorsolateral portions. The medial prefrontal cortex is responsible for organizing and integrating information, while the dorsolateral regions are in charge of self-control, self-monitoring and self-censoring.

The researchers also found that the medial prefrontal cortex lit up at the same time as language and motor areas of the brain — no surprise given that rappers had to think of words and produce them with the muscles of the mouth and jaw. This network of brain areas also communicated heavily with the amygdala during freestyle rapping, likely indicating emotional activity, a function of this deep-brain almond-shaped structure.

Toward the end of the 8-bar track, attentional areas in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex started to wake up, the researchers found, suggesting that wrapping up a rap requires a bit more control and attention.

Eagle and Rizik-Baer rated the rappers' freestyle tracks for creative use of language. The researchers found that the highest-rated rappers had more activity in the upper part of the medial prefrontal cortex. They also showed lots of activity in the posterior lateral temporal region of the brain, the back section of the brain lobe that sits behind the ear. This section is traditionally linked to mental lexicon, or vocabulary.

The researchers aren't yet sure if this improvising brain network can be trained for quicker thinking, but the study does suggest there's nothing magic about creativity, Allen said.

"These are just simple rearrangements of brain activity and cognitive processes that are a normal part of everyday experiences," he said.

The researchers report their findings today (Nov. 15) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.