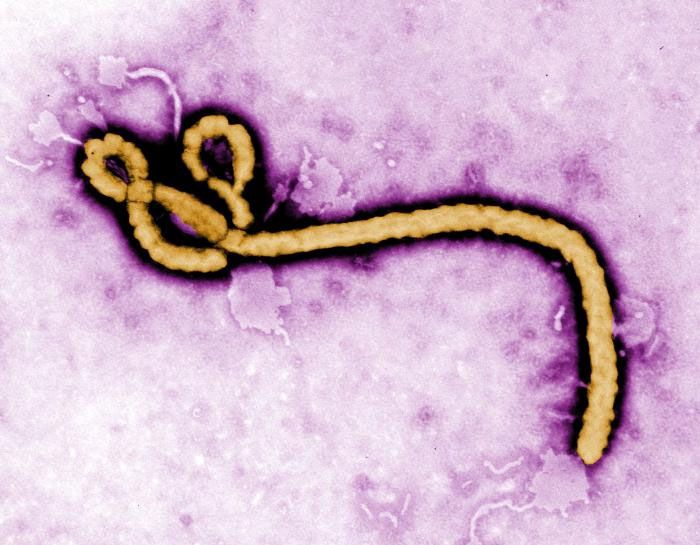

Step Taken Toward Ebola Vaccine

Vaccines tested on monkeys, guinea pigs and mice have revealed a chemical marker that can accurately indicate whether one is protected from the deadly Ebola virus, bringing a human vaccine closer to reality.

Ebola, more formally called Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is actually five viruses, named according to where they were first found. Likely the most well-known of the viruses, Zaire ebolavirus, has reported mortality rates of up to 90 percent, although it has been as low as 25 percent, according to the World Health Organization. There is no cure for Ebola, nor is there a vaccine approved yet for human use.

Currently, an outbreak of the Sudan strain of Ebola has killed three in Uganda, with several others being monitored. And while the disease is quite rare and endemic to remote areas of Africa, it is often touted as a possible biological weapon. Aside from such apocalyptic scenarios, there is the problem of travelers who might become infected and spread it to others. Laboratory and health-care workers are also vulnerable. The virus is spread by close contact and bodily fluids, though there is still some debate as to how it is spread in natural settings.

Animal testing

In the new study, scientists led by Gary Kobinger, chief of special pathogens at the Public Health Agency of Canada, tested two vaccines on monkeys, guinea pigs and mice. When a vaccine is administered, or an infection occurs, the body produces chemicals called immunoglobulins, a type of antibody. These chemicals latch on to the invading bacteria or virus and alert the immune system to attack it. Kobinger found that high levels of so-called immunoglobulin G (IgG) correlated with surviving infection with Ebola. [5 Things You Should Know About Ebola]

"What this tells you is what can you look at with the immune response that can tell us if this person is protected," he said. That is, if one were to use the same test on humans, one could say with 99.97 percent confidence that they are protected.

"This is a critical link needed to advance the vaccine platforms to human clinical trials," said Gene Olinger, supervisory microbiologist at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Md., who was not involved in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of the vaccines tested is scheduled for testing in humans in 2013, Kobinger said. The new study, detailed in the Oct. 31 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine, makes it easier to justify such human clinical trials.

Testing an Ebola vaccine is tricky, because the disease is so deadly and rare. With measles or hepatitis, there is already a widespread population infected, so scientists can test the vaccine in those individuals. But with Ebola, one would have to expose humans to the virus to get a large enough sample, something that could never happen ethically.

Some of the first attempts to make a vaccine used an Ebola virus rendered inactive, said Heinz Feldmann, chief of the Laboratory of Virology at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Mont. The method is a common (and successful) one, having been used for diseases such as polio. But the method didn't work as well as researchers wanted. In some cases, the animals seemed to be protected, while higher doses of the "benign" virus killed them.

Benign delivery system

Now there are a number of methods for delivering the proteins on the virus' surface and stimulating the IgG response without using the actual infectious agents — in this case, the Ebola virus. Kobinger used adenovirus and vesicular stomatitis virus, modified so they don't cause disease. Both methods resulted in similar levels of IgG and protection from Ebola. (It is the adenovirus-based vaccine that will be tested on humans first).

This looks promising, but there are some important caveats. For instance, the study shows something that correlates with protection from Ebola. That doesn't mean IgG is what is protecting the animals from the disease; it is still not clear exactly how the immune system stops the virus from growing and spreading.

Testing for levels of IgG will be a good way to see if someone is protected from the virus, and that's why human trials are possible. But ultimately, the only way to know for certain if a vaccine is effective is to test it against an infection. That's likely to be in an outbreak in a remote area, or by giving it to lab workers. That raises ethical questions of its own, even if — or perhaps especially if — the vaccine works. "If I think we have something for us [in the lab], you can't not give it to people," Feldmann said. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Another issue is whether you would vaccinate lots of people at all. Ebola is so rare that unless there's a major outbreak, it may not be worth giving vaccines to thousands of people in say, New York. It is possible for travelers to bring it back, but given how remote the endemic areas are, that's pretty unlikely. Perhaps the biggest population worth giving it to is health-care workers in endemic areas, though that is still a small group relative to the population.

More immediately, Kobinger said, this kind of correlation could be a way to help people dealing with outbreaks: Doctors could test a patient's levels of IgG specific to Ebola, and if they're high, then it's likely they are protected and therefore won't infect anyone else.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Most Popular