Destroying a dangerous asteroid with a nuclear bomb is a well-worn trope of science fiction, but it could become reality soon enough.

Scientists are developing a mission concept that would blow apart an Earth-threatening asteroid with a nuclear explosion, just like Bruce Willis and his oilmen-turned-astronaut crew did in the 1998 film "Armageddon."

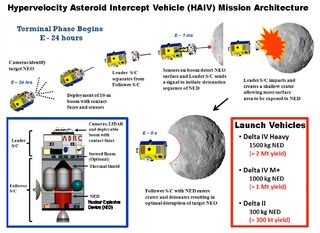

But unlike in the movie, the spacecraft under development — known as the Hypervelocity Asteroid Intercept Vehicle, or HAIV — would be unmanned. It would hit the space rock twice in quick succession, with the non-nuclear first blow blasting out a crater for the nuclear bomb to explode inside, thus magnifying its asteroid-shattering power.

"Using our proposed concept, we do have a practically viable solution — a cost-effective, economically viable, technically feasible solution," study leader Bong Wie, of Iowa State University, said Wednesday (Nov. 14) at the 2012 NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) meeting in Virginia. [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

When, not if

Earth has been pummeled by asteroids throughout its 4.5-billion-year history, and some of the strikes have been catastrophic. For example, a 6-mile-wide (10 kilometers) space rock slammed into the planet 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs.

Earth is bound to be hit again, and relatively soon. Asteroids big enough to cause serious damage today — not necessarily the extinction of humans, but major disruptions to the global economy — have hit the planet on average every 200 to 300 years, researchers say.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So humanity needs to have a plan in hand to deal with the next threatening asteroid, many scientists stress.

That plan should include deflection strategies, they say. Given a few decades of lead time, a threatening space rock could be nudged off course — perhaps by employing a tag-along "gravity tractor" probe, or even by painting the asteroid white and letting sunlight give it a push.

But humanity also needs to be prepared for an asteroid that pops up on scientists' radar just weeks before a potential impact. That scenario might demand the nuclear option that Wie and his colleagues are working to develop.

A one-two punch

NASA engineers identified 168 technical flaws in "Armageddon," Wie said. But one thing the movie got right is the notion that a nuke will be far more effective if it explodes inside an asteroid rather than at its surface. (At a depth of 10 feet, or 3 meters, the bomb's destructive power would be about 20 times greater, Wie said.)

So Wie and his team came up with a way to get the bomb down into a hole, without relying on a crew of spacewalking roughnecks to bore into the space rock.

The HAIV spacecraft incorporates two separate impactors, a "leader" and a "follower." As HAIV nears the asteroid, the leader separates and slams into the space rock, blasting out a crater about 330 feet (100 m) wide.

The nuke-bearing follower hits the hole a split-second later, blowing the asteroid to smithereens. Simulations suggest the explosion would fling bits of space rock far and wide, leaving only a tiny percentage of the asteroid's mass to hit Earth, Wie said.

This is no pie-in-the sky dream: The researchers have received two rounds of funding from the NIAC program, and they say their plan is eminently achievable.

"Basically, our proposed concept is an extension of the flight-proven $300 million Deep Impact mission," Wie said, referring to the NASA effort that slammed an impactor into Comet Tempel 1 in 2005.

Demonstration mission coming?

The HAIV project is still in its early stages, and much more modeling and developmental work is needed. But Wie and his colleagues are ambitious, with plans for a bomb-free flight test in the next decade or so.

"Our ultimate goal is to be able to develop about a $500 million flight demo mission within a 10-year timeframe," Wie said.

The team's current work involves analyzing the feasibility of nuking a small but still dangerous asteroid — one about 330 feet (100 m) wide — with little warning time. However, it wouldn't be too difficult to scale up, Wie said.

"Once we develop technology to be used in this situation, we are ready to avoid any collision — with much larger size, with much longer warning time," Wie said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.