Image Gallery: Fossils Reveal Rhino's Grisly Death

Rhino Fossils

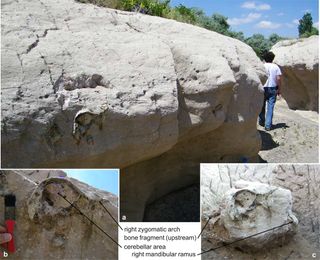

Researchers discovered the cranium and mandible of an ancient rhino species, called Ceratotherium neumayri in Cappadocia in Central Turkey. Though the researchers have discovered fossils of soft-bodied organisms preserved in volcanic ash, the high temperatures near eruptions generally destroy organic matter, making this fossil extremely rare.

Just a Teenager

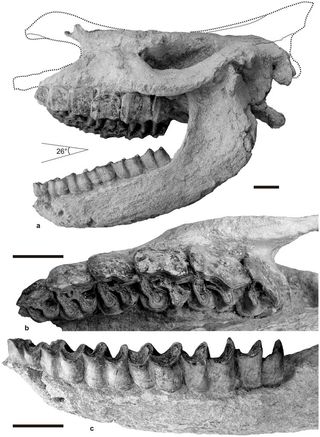

When alive, the rhino (Ceratotherium neumayri) would have weighed between 3,300 and 4,400 pounds (1,500 and 2,000 kilograms), about the size of a young white rhino, though sporting a shorter head, Antoine said. The animal was 10 to 15 years old, a young adult, when it died in a Pompeii-style eruption.

That's Hot

Here, the cranium and mandible of the rhino are shown as they may have appeared when the animal was alive some 9.2 million years ago. The corrugated features on the bony surfaces likely indicate they were exposed for a good length of time to warm volcanic material. In addition to the cranium and mandible, a broken rib (b) was found trapped upstream, though the researchers can't say if it belonged to the same individual rhino.

Tooth Tales

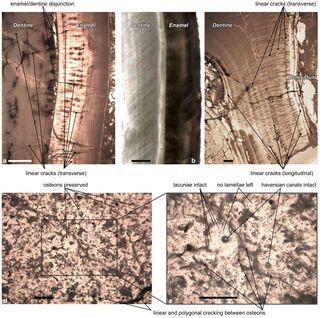

Using light microphotographs of the hard tissues of the fossils, researchers found evidence of intense heating, like that from a Mt. Vesuvius-like eruption. For instance, they saw separation of the enamel and dentine and a network of cracks. They compared the results with an unheated rhino tooth rhino tooth (b) showing no structural changes. The roots of one of the molars (c) also showed signs of heating, as did the right nasal bone (d).

Cooked to Death

The researchers think the rhino's body was baked and dismembered by the sizzling-hot volcanic flow. The flow of volcanic ash carried the detached skull about 19 miles (30 kilometers) north of the eruption site and to the site where it was discovered in Cappadocia in Central Turkey.

Volcanic Landscape

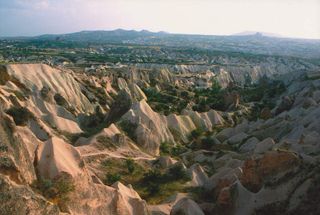

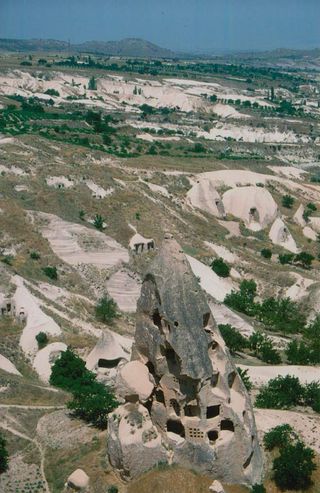

The so-called Çardak caldera, which spread huge amounts of ash over Cappacocia, is inactive today. Even so, thick layers of volcanic ash have accumulated over millions of years. "Then, erosion generated there among the most magnificent landscapes I've ever seen," said study researcher Pierre-Olivier Antoine of the University of Montpellier in France.

Neverending Beauty

Here, the very area in Cappadocia where the rhino fossil was found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.