Fossil Fly's Camouflage Tricks Scientists

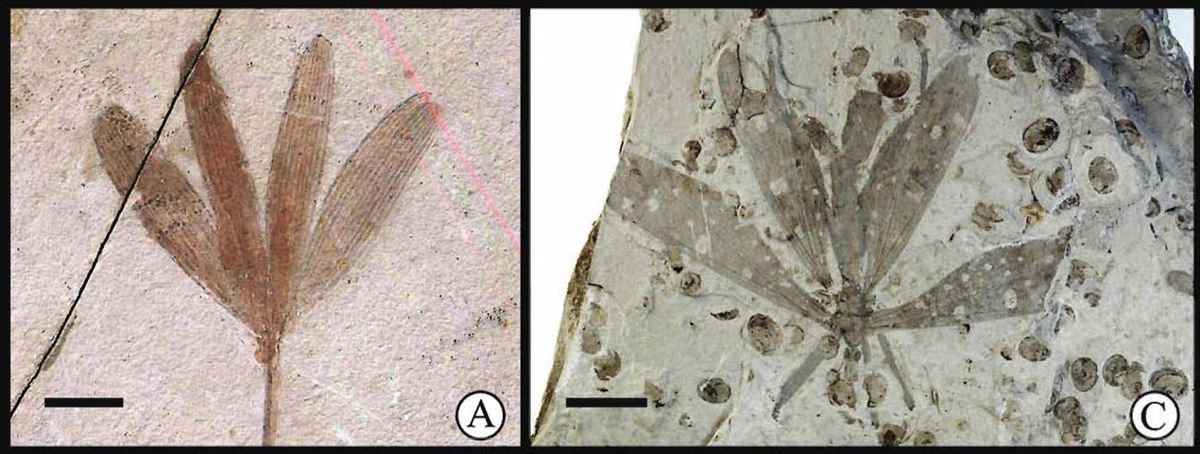

A fossilized scorpionfly that apparently mimicked the leaves of an ancient ginkgo-like tree has just been unearthed, researchers say.

The finding adds to evidence that this form of camouflage is very ancient, the scientists added.

More than 100 years ago, scientists began noticing extraordinary resemblances between insects and plants in the fossil record, such as those between certain roaches and the leaflets of particular seed ferns. Such mimicry, also seen in living animals, likely helps protect creatures from predators, or might help them sneak up on prey.

Now paleoentomologist Dong Ren at Capital Normal University in Beijing and his colleagues have discovered another such plant mimic in northeastern China's Inner Mongolia region.

Fossil mimic

The 165-million-year-old insect in question is a species of scorpionfly, a group that gets its name from the insects' enlarged male genitals that resemble scorpion stingers. Specifically, the fossil, which was about 1.5 inches (38.5 millimeters) long, is a type of scorpionfly known as a hangingfly, which often hangs from surfaces waiting to snag prey.

The region back then was a large, relatively shallow lake basin containing both lakeside forest and shrubland, much of which was adapted to a seasonal and somewhat arid climate. The dominant plants were now-extinct relatives of familiar conifers, ginkgos, ferns and horsetails.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the hangingfly (Juracimbrophlebia ginkgofolia) that was fossilized in this find stretched its wings, it would have resembled the five-lobed leaf of an extinct ginkgo-like tree (Yimaia capituliformis) that once dwelled in the region. The scientists accidentally ran across this mimicry about a year and a half ago, after initially mistaking the insect for a leaf in the lab and the field.

The researchers suggest the hangingfly may have evolved this mimicry to hide from predators, since its relatively large body and weak legs and wings would have made it easy prey. The insect also may have used mimicry to help ambush prey. This was a potentially mutually beneficial relationship with its host, with the tree providing shelter, while the insect devoured creatures that might otherwise munch on the plant. [Dazzling Photos of Dew-Covered Insects]

Evolution of a mimic

Nearly all of the insect mimicry documented today and for the past 100 million years involves the flowering plants, known as angiosperms. This newfound mimic, however, involves ginkgo-like lineages, which are not flowering plants, "and presages some types of mimicry that occurred tens of millions of years later with angiosperms and more modern insect lineages," researcher Conrad Labandeira, a paleoecologist and curator of fossil arthropods at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, told LiveScience.

As such, the findings revealed this form of plant mimicry evolved long before the flowering plants arrived.

"The mere occurrence of this type of mimicry approximately 40 million years before the appearance of flowering plants is the most important implication" of our finding, Labandeira said.

This ginkgo-like plant likely went extinct during the heyday of the dinosaurs, and this form of mimicry apparently died along with it.

Ren, Labandeira and their colleague Yongjie Wang detailed their findings online Nov. 26 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.