Nasty Wound Leads to Bacteria Discovery

An Indiana man's nasty injury led scientists to discover a new type of bacteria that sheds light on symbiotic microbes in insects.

Two years ago, Thomas Fritz cut down a dead crab apple tree in his yard. He fell while hauling away the woody debris and a branch from the tree impaled his right hand between the thumb and index finger.

Fritz, a 71-year-old retired inventor, engineer and volunteer firefighter, bandaged the gash himself. He waited a few days to see a doctor and by the time of his appointment, the puncture wound became infected. The doctor took a sample of the cyst that formed at the site of the cut and sent it to a lab.

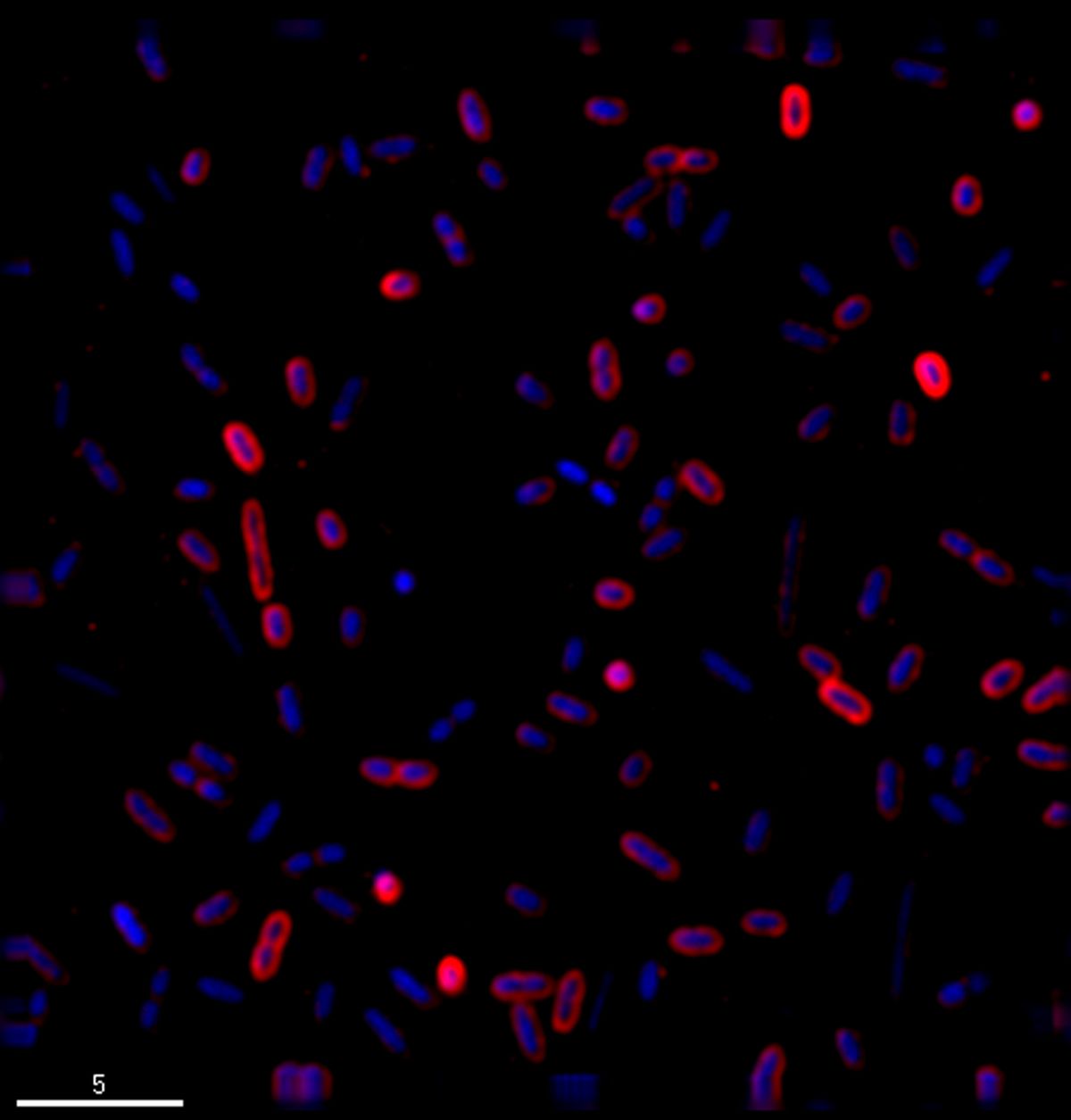

After an abscess, swelling and more pain, Fritz's wound eventually healed. But the sample from his infection puzzled scientists at the lab who couldn't identify what type of bacteria they were looking at. The sample was eventually sent to ARUP Laboratories, a national pathology reference library operated by the University of Utah, where scientists named the new strain human Sodalis or HS.

Colin Dale, a biologist at the University of Utah, said that genetic analyses of HS showed it is related to Sodalis, a genus of bacteria that he discovered in 1999 and has been found to live symbiotically in 17 insect species, including tsetse flies, weevils, stinkbugs and bird lice. In such symbiotic relationships, both the host and the bacteria gain — for example, while Sodalis bacteria get shelter and nutrition from their insect hosts, they also provide the insects vital B vitamins and amino acids.

Though symbiotic relationships between microorganisms and insects are common, their origins are often a mystery. The new evidence provides "a missing link in our understanding of how beneficial insect-bacteria relationships originate," Dale said, adding that the findings show that these relationships arise independently in each insect.

As the strain of Sodalis in this case likely came from a tree, the discovery suggests that insects can get infected by pathogenic bacteria from plants or animals in their environment, and the bacteria can evolve to become less virulent and to provide symbiotic benefits to the insect. Then, instead of spreading the bacteria to other insects by infection, mother insects pass down the microbes to their offspring, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The insect picks up a pathogen that is widespread in the environment and then domesticates it," Dale explained in a statement from the National Science Foundation, which funded the research. "This happens independently in each insect."

The research was detailed earlier this month online in the journal PLoS Genetics.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.