400-Year-Old Playing Cards Reveal Royal Secret

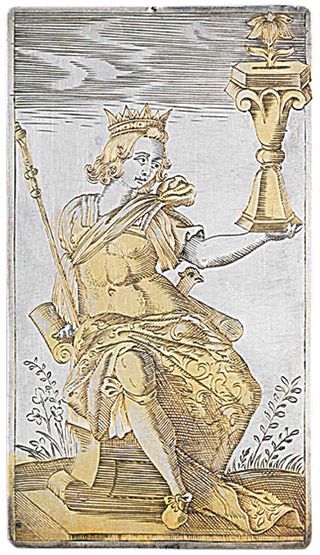

Call it a card player's dream. A complete set of 52 silver playing cards gilded in gold and dating back 400 years has been discovered.

Created in Germany around 1616, the cards were engraved by a man named Michael Frömmer, who created at least one other set of silver cards.

According to a story, backed up by a 19th-century brass plate, the cards were at one point owned by a Portuguese princess who fled the country, cards in hand, after Napoleon's armies invaded in 1807.

At the time they were created in 1616 no standardized cards existed; different parts of Europe had their own card styles. This particular set uses a suit seen in Italy, with swords, coins, batons and cups in values from ace to 10. Each of these suits has three face cards — king, knight (also known as cavalier) and knave. There are no jokers. [See Photos of the Silver Playing Cards]

In 2010, the playing cards were first put on auction by an anonymous family at Christie's auction house in New York. Purchased by entrepreneur Selim Zilkha, the cards were recently described by Timothy Schroder, a historian with expertise in gold and silver decorative arts, in his book "Renaissance and Baroque Silver, Mounted Porcelain and Ruby Glass from the Zilkha Collection"(Paul Holberton Publishing, 2012).

"Silver cards were exceptional," Schroder writes. "They were not made for playing with but as works of art for the collector's cabinet, or Kunstkammer." Today, few survive. "[O]nly five sets of silver cards are known today and of these only one — the Zilkha set — is complete."

On the cards, two of the kings are depicted wearing ancient Roman clothing while one is depicted as a Holy Roman Emperor and another is dressed up as a Sultan, with clothing seen in the Middle East. . The knights and knaves are depicted in different poses wearing (then-contemporary) Renaissance military or courtly costumes. Each card is about 3.4 inches by 2 inches (8.6 centimeters by 5 centimeters) in size and blank on the back.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gilding with mercury

Creating the card set would have been a hazardous job. For the gilding, its designers used mercury, a poisonous substance that can potentially kill.

"You ground up gold into kind of a dust, and you mix it with mercury, and you painted that onto the surface where you wished the gilding to appear," Schroder told LiveScience in an interview. The mercury gets burned off in a kiln, a process "that would leave the gold chemically bonded to the silver."

The process is illegal today, he noted, and even in Renaissance times, it was known to be hazardous. "I don't think they quite understood why it was dangerous, but they did appreciate the dangers of it," Schroder said.

A gift from a princess?

The owner of the 17th-century card set is not known. However, according to a tradition detailed by the anonymous family who sold it, in the early 19thcentury, the cards were in the possession of Infanta Carlota Joaquina, a daughter of a Spanish king, who was married to a prince in Portugal. She fled to Brazil when Napoleon's armies marched into Iberia in 1807, apparently taking the silver cards with her.

After Napoleon forced her brother, Ferdinand VII, to abdicate the throne of Spain, she made several attempts to take over the Spanish crown and control the country's holdings in the New World. According to the family tradition, she gave the card set to the wife of Felipe Contucci, a man who helped in her efforts.

While this story cannot be proven, Schroder said he has "very little reason to doubt it." He added that "when the cards were acquired by Mr. Zilkha, they came in an early 19th-century leather box which had a brass plate in them, which also appeared to date from the early or middle of the 19th century, with this provenance engraved on it."

Contucci's plot

Spain still controlled a vast empire in the New World at the time of Napoleon's invasion. Among its territories was the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, a large swath of land centred in Buenos Aires (in modern-day Argentina).

In November 1808, Contucci was in contact with leaders in Buenos Aires, according to a conference paper presented last February by Anthony McFarlane, a professor at the University of Warwick. Contucci told the princess they had made her an offer that would see her gain control of a new kingdom in South America. [Top 12 Warrior Moms in History]

McFarlane writes that "Contucci raised her hopes by informing in mid-November 1808 that 124 leading men were ready to support a military intervention by a military force led by the Infante Pedro Carlos [a relative of the princess] and supported by Admiral Smith [of Britain], to install her (as) the constitutional monarch of an independent kingdom."

However, this plan was foiled when government officials from Portugal, Spain and Britain all objected to it.

Then, in August 1809, the Spanish ambassador arrived in Rio with instructions from the Junta Central (the Spanish government not controlled by Napoleon), "to prevent Carlota from entering Spanish territory and to deflect her ambitions to become Regent," writes McFarlane.

Carlota's dream of becoming a ruling queen was simply not in the cards.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.