Voyager 1 Spacecraft Enters New Realm at Solar System's Edge

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft has discovered a new layer of the solar system that scientists hadn't known was there, researchers announced today (Dec. 3).

Voyager 1 and its sister probe Voyager 2 have been traveling through space since 1977, and are close to becoming the first manmade objects to leave the solar system.

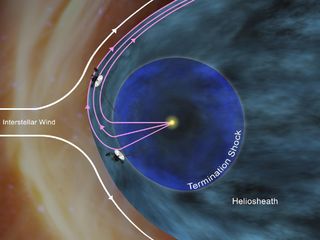

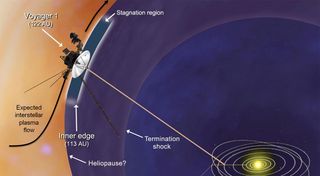

Scientists haven't been sure exactly when that exit would occur, and now say the spacecraft are likely in the outermost region of the solar system, which is defined by the extent of the heliosphere, the large bubble of charged particles the sun puffs out around itself. Voyager 1, in particular, has entered a new region of the heliosphere that scientists are calling a "magnetic highway," which allows charged particles from inside the heliosphere to flow outward, and particles from the galaxy outside to come in.

"We do believe this may be the very last layer between us and interstellar space," Edward Stone, Voyager project scientist based at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, Calif., said during a teleconference with reporters. "This region was not anticipated, was not predicted."

Therefore, he said, it's hard to predict how soon Voyager will leave the solar system behind altogether. [How NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes Work (Infographic)]

"We don’t know exactly how long it will take," Stone said. "It may take two months, it may take two years."

The scientists don't think the Voyagers have left the solar system yet because of the orientation of the magnetic field they detect. So far, this field still runs east-west, in agreement with the field created by the sun and twisted by its rotation. Outside the solar system, models predict the magnetic field to be orientated more north-south.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As Voyager 1, the outermost of the two spacecraft, gets farther and farther away, it measures more and more of the higher-energy charged particles thought to originate beyond the solar system, compared to the lower-energy particles thought to come from the sun.

"Things have actually changed dramatically," said Stamatios Krimigis, principal investigator of the low-energy charged particle instrument, based at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. "The particles from outside have increased a lot and those on the inside … have dropped quite a bit."

The Voyagers are NASA's longest-running spacecraft, and will keep traveling outward even after they've left the sun's neighborhood. However, it will be at least 40,000 years before they ever come close to another star, Stone said.

Long before that the probes will run out of power to operate their scientific instruments and beam their findings back home.

"We will have enough power for all the instruments until 2020; at that point we will have to turn off our first instrument," Stone said. By 2025 the last instrument will have to be turned off.

"We're very lucky that there seems to be a compatibility between our mission and the extent of the heliosphere," Stone said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.