SAN FRANCISCO — The chief scientist for NASA's Mars rover Curiosity was just excited about the mission, and thrilled that one of the six-wheeled robot's key instruments was acing its first Red Planet tests. That's all he meant to convey.

But when an NPR story last month quoted John Grotzinger as saying that data recently gathered by Curiosity's Sample Analysis at Mars instrument, or SAM, were destined "for the history books," the world imposed its own interpretation.

Rumors begin flying around the Internet that SAM had perhaps detected complex organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — on the Red Planet.

What Curiosity found

SAM's actual findings, which were revealed Monday (Dec. 3) in a press conference here at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, are intriguing but fall a bit short of the fevered speculation. SAM has detected simple, chlorinated organics — chemicals containing carbon and at least one chlorine atom — but it's unclear if the carbon within them is native to Mars or whether it hitched a ride from Earth, researchers said.

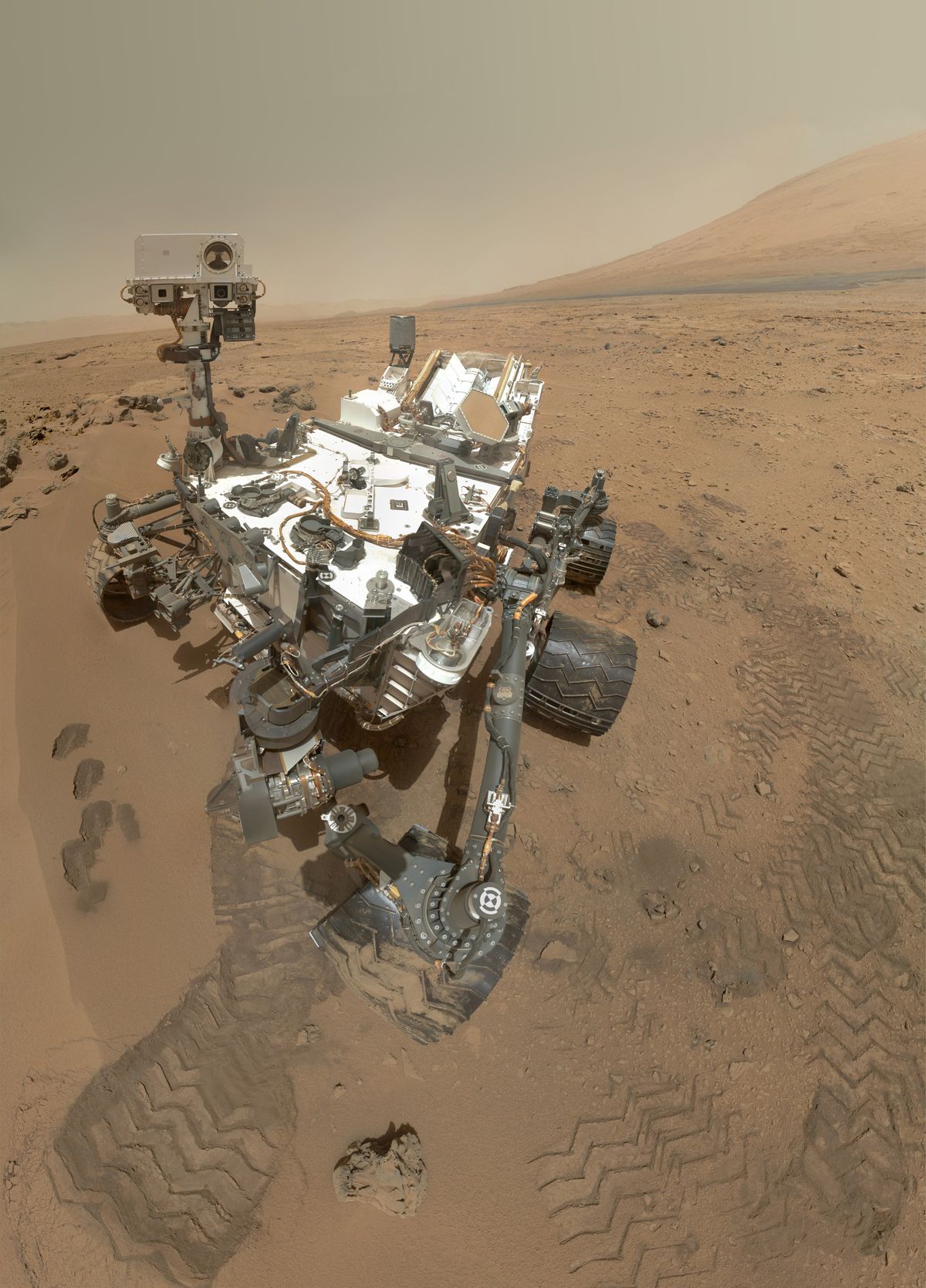

Grotzinger, a geologist at Caltech in Pasadena, said he meant to convey the excitement his team felt to see SAM — a mobile chemistry lab that takes up more than half of Curiosity's science payload by weight — working according to plan on Mars. [Organic Compounds On Mars - Did Curiosity Bring it? | Video]

He was surprised by the way his words rocketed around the Internet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We're doing science at the speed of science. We live in a world that's sort of at the pace of Instagrams," Grotzinger said during Monday's press conference. "The enthusiasm that we had — that I had, that our whole team has about what's going on here — I think was just misunderstood."

"What I've learned in this is that you have to be careful about what you say, and even more careful about how you say it," he added.

After some reflection, Grotzinger came to see some positives in the way the world latched onto his words.

"As the days went by and I thought about it further, my reaction was, I think it's terrific that this mission has such wide appeal and public interest," he said. "That's everything that I think we're hoping for, and the mission has delivered an unbelievable wealth of data."

Chlorinated compounds

SAM heats up soil samples and identifies the chemical species that boil out of the dirt. It's possible that the newly observed chlorinated compounds result from the decomposition of perchlorate, a chemical that NASA's Phoenix lander detected near the Martian north pole in 2008, researchers said.

"I think it's very likely that the chlorinated compounds that we saw — chloromethane, dichloromethane and trichloromethane — were actually produced as this perchlorate broke up and some very reactive chlorine was released, and then that reacted with carbon," said SAM principal investigator Paul Mahaffy of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

"The thing we have to untangle is, what form of carbon was that reacting with?" Mahaffy added. "Was it some of the CO2 that was being released also, at the same time? Or was it from some other source of carbon?"

The Curiosity team is working on such questions right now, as the rover nears its four-month anniversary on the Martian surface. The $2.5 billion rover landed Aug. 5 inside Mars' huge Gale Crater, kicking off a two-year prime mission to determine if the Red Planet could ever have supported microbial life.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.