Cavemen Trump Modern Artists at Drawing Animals

Paleolithic people living more than 10,000 years ago had a better artistic eye than modern painters and sculptures — at least when it came to watching how horses and other four-legged animals move.

A new analysis of 1,000 pieces of prehistoric and modern artwork finds that "cavemen," or people living during the upper Paleolithic period between 10,000 and 50,000 years ago, were more accurate in their depictions of four-legged animals walking than artists are today. While modern artists portray these animals walking incorrectly 57.9 percent of the time, prehistoric cave painters only made mistakes 46.2 percent of the time.

Modern artists are also worse at capturing the gait of horses and other quadrupeds than taxidermists, anatomy textbook writers and toy figurine designers, the researchers report today (Dec. 5) in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Four-legged gait

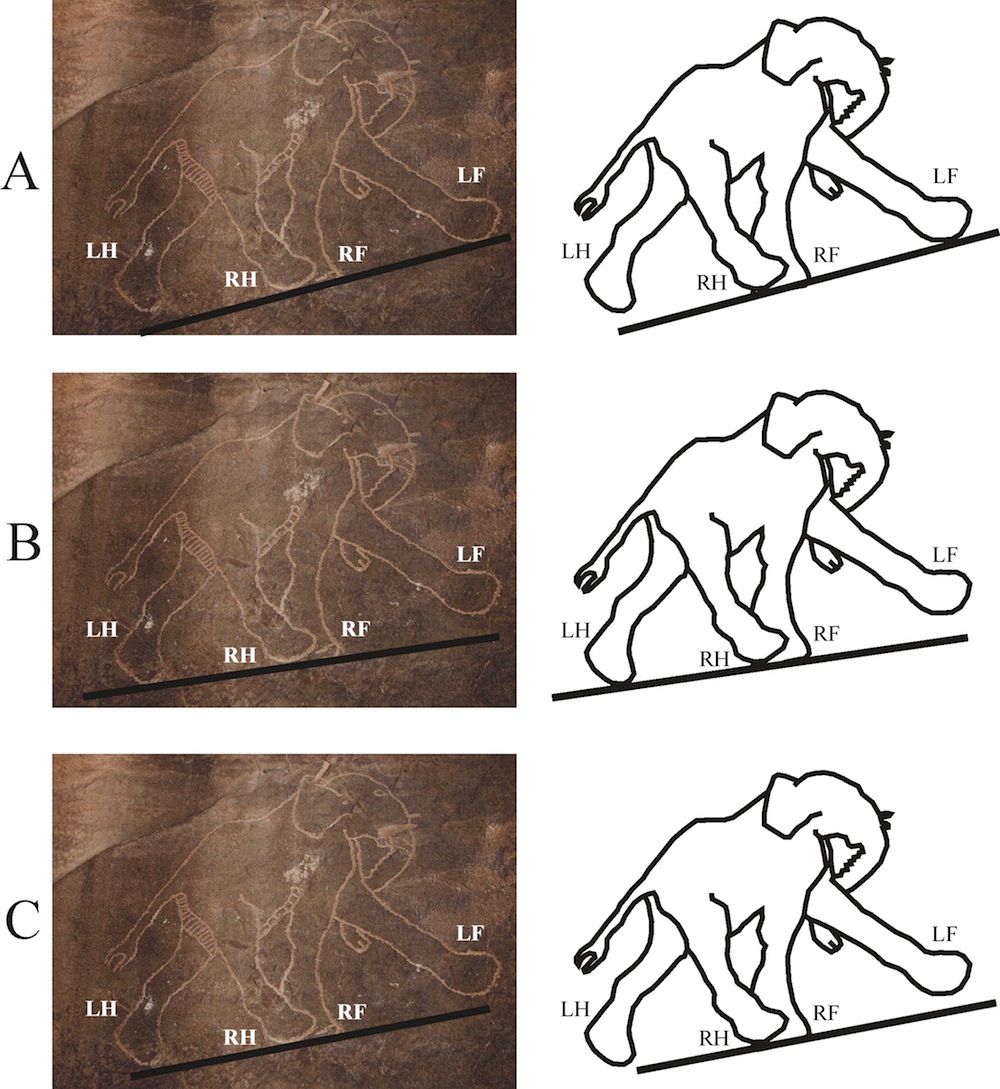

Four-legged animals walk by moving their legs in the same sequence. First, the left-hind foot hits the ground, then the left-front foot, followed by the right-hind foot and finally the right-front foot. Only the speed at which four-legged animals complete this sequence differs.

But this simple gait often escapes the notice of artists. In 2009, biological physicist Gabor Horvath, a researcher at Eotvos University in Hungary, found that 63.6 percent of the animals depicted in anatomy textbooks were drawn in impossible gaits. Half of toy horses, lions, tigers and other quadrupeds were also wrong. Even depictions in natural history museums failed much of the time: Just over 41 percent of those showed errors.

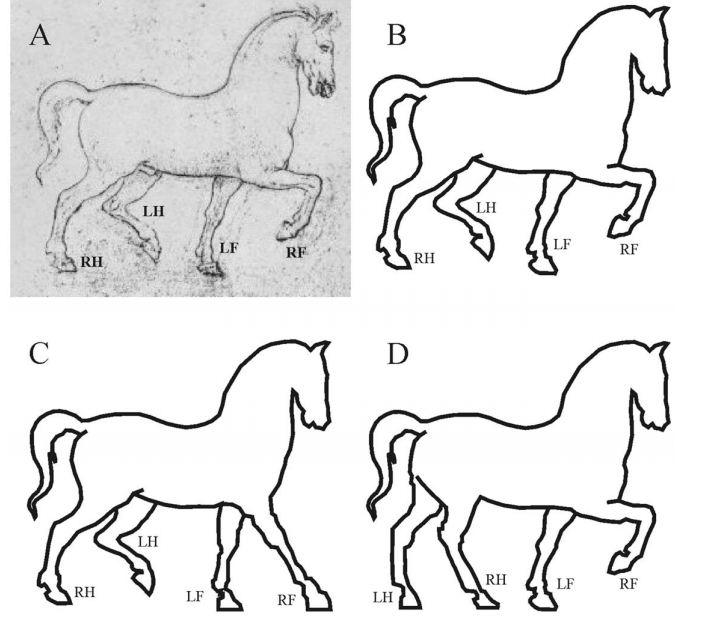

In the new study, Horvath and his colleagues wanted to look at the same question over the history of art. In the 1880s, photographer Eadweard Muybridge used motion pictures to show how horses and other quadrupeds really walked. This knowledge spread, so Horvath and his colleagues split their analysis into three time periods: prehistoric art, historical art made before Muybridge's work, and art made after 1887, when Muybridge's work would have been public. [Gallery: Where Science Meets Art]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Getting animals right

The researchers plucked 1,000 examples of art from online collections, fine art books and Hungarian museums, as well as on stamps and coins. Chance alone would dictate that artists mess up depictions of four-legged gait 73.3 percent of the time, the researchers calculated. But art produced after prehistory but before Muybridge showed more errors than chance would allow. In fact, 83.5 percent of depictions from this time period were wrong.

The erroneous drawings even included one sketch of a horse by Leonardo da Vinci, known for his anatomical sketches. In the sketch, the horse has its right-hind foot and left-front foot down with its other two feet lifted, an unstable position. In fact, four-legged animals keep three legs on the ground at any given time.

It's possible that the high level of pre-Muybridge errors may reflect artists mimicking their peers' un-anatomical work, the researchers wrote. But Paleolithic man seems to have been a keen observer of four-footed fauna. Cave art got its depictions right about 54 percent of the time, far better than chance.

Muybridge's work did improve depictions of four-legged walks, the study suggests, but with a success rate of 42 percent, post-1880s artists still aren't doing as well as cavemen. Taxidermists squeak by with a success rate of about 57 percent, according to Horvath's 2009 work.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.