Landslide-Driven Megatsunamis Threaten Hawaii

SAN FRANCISCO — It's almost unimaginable: a tsunami more than 1,000 feet (300 meters) high bearing down on the island of Hawaii.

But scientists have new evidence of these monster waves, called megatsunamis, doing just that. The findings were presented here yesterday (Dec. 5) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Unlike tsunamis from earthquakes, the Hawaiian tsunamis strike when the island chain's massive volcanoes collapse in humongous landslides. This happens about every 100,000 years, and is linked to climate change, said Gary McMurtry, a professor at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

Sitting about 30 feet (10 m) away from today's Ka Le (South Point) seashore are boulders the size of cars. Some 250,000 years ago, a tsunami tossed the enormous rocks 820 feet (250 m) up the island's slopes, said Fernando Marques, a professor at the University of Lisbon in Portugal. (The boulders are closer to the shore now because the main island of Hawaii is one of the world's largest volcanoes, and its massive weight sends it sinking into the Earth at a rate of about 1 millimeter a year.)

McMurtry's team found two younger and slightly smaller tsunami deposits at South Point on the main island of Hawaii, one 50,000 years old and one 13,000 years old. He suggests the tsunami source is the two Ka Le submarine landslides, from the flanks of the nearby Mauna Loa volcano. The waves carried corals and 3-foot (1 m) boulders 500 feet (150 m) inland.

Deadly, landslide-triggered tsunamis happen at volcanic islands around the world, and are a potential hazard for the Eastern United States. "We find them everywhere, but we don't know of any historical cases, so we have to go back in time," said Anthony Hildenbrand, a volcanologist at the University of Paris-Sud in France, who helped identify the ancient tsunami deposit.

The falling rock acts like a paddle, giving the water a sudden push. While landslide tsunamis may have a devastating local effect, they lose their power in the open ocean and don't destroy distant coastlines like earthquake tsunamis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The giant landslides seem to happen during periods of rising sea levels, when the climate is also warmer and wetter, Hildenbrand told OurAmazingPlanet. Researchers speculate that the change from lower sea level to higher may destabilize a volcanic island's flanks, and heavier rains could soak its steep slopes, helping trigger landslides.

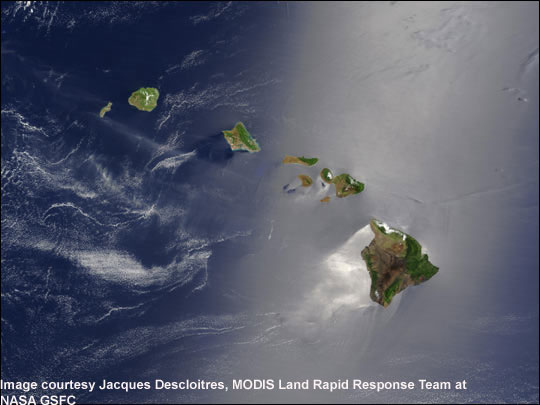

There are at least 15 giant landslides that have slid off the Hawaiian Islands in the past 4 million years, with the most recent happening only 100,000 years ago, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. One block of rock that slid off Oahu is the size of Manhattan.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.