SAN FRANCISCO — The last manned mission to the moon launched 40 years ago today, but astronaut Harrison Schmitt remembers it like it was yesterday.

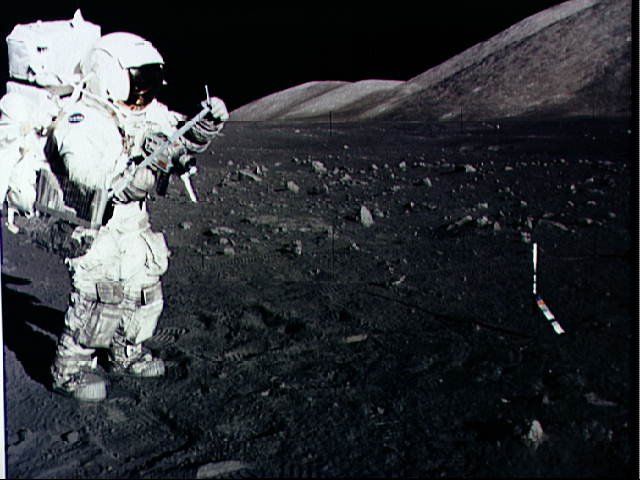

NASA's Apollo 17 mission blasted off in the early hours of Dec. 7, 1972, carrying Schmitt, Gene Cernan and Ron Evans toward Earth's nearest neighbor. Four days later, Schmitt became the 12th and final person — and the only trained geologist — to set foot on the moon when he and Cernan emerged from their lunar module, Challenger.

The passage of four decades has not dimmed Harrison "Jack" Schmitt's recollections much.

"The memory is extremely vivid," Schmitt said here Thursday (Dec. 6) at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. "And I actually refer back to the transcripts enough that I think I'm keeping that memory correct." [Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos]

No particular moment from the 12-day mission stands out as his favorite, he added.

"I treasure the whole mission. Every day had more than one really spectacular event," Schmitt said. "The first day, we saw this nearly full Earth, and I was able to take that picture of Africa — still the most-requested photograph in the NASA archives. And it just went on from that."

Schmitt did identify one Apollo 17 science find as particularly important, however — the discovery of "orange soil," which turned out to be composed of tiny beads of volcanic glass. Recently, researchers spotted trace amounts of water within these beads and others like them brought back to Earth by Apollo astronauts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery of indigenous lunar water has helped reshape scientists' understanding of the moon's formation and how it has evolved over time.

No person has set foot on the moon since Schmitt and Cernan clambered back into the Challenger lunar module for the final time 40 years ago. But Schmitt thinks that should change, and soon.

He advocates for a human return to the moon, which could serve as a stepping stone to other deep-space destinations such as near-Earth asteroids and Mars.

"By going back to the moon, you accelerate your ability to go anywhere else — both in terms of experience and in terms of resources, and testing new hardware and navigation techniques, communication techniques and things like that," Schmitt said. "And it's only three days away."

NASA is currently working to get astronauts to an asteroid by 2025 and then on to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s, as directed by President Barack Obama. The space agency is developing a crew capsule called Orion and a huge rocket known as the Space Launch System to make this happen.

SLS and Orion could also carry astronauts to the moon and its environs, and NASA officials have recently stated a desire to do just that.

"We just recently delivered a comprehensive report to Congress outlining our destinations which makes clear that SLS will go way beyond low-Earth orbit to explore the expansive space around the Earth-moon system, near-Earth asteroids, the moon, and ultimately, Mars," NASA deputy chief Lori Garver said at a conference in September.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.