Image Gallery: A Tiny Creature with Bizarre Features

Hidden Gem

About 200 million years ago, a leech released a slimy mucous cocoon that unwittingly encased and trapped a bizarre animal with a springy tail, preserving it for eternity, or until researchers discovered the teardrop-shape creature in Antarctica recently.

Fast Contractor

The critter most closely resembled the genus Vorticella, more specifically, Vorticella campanula, whose rapidly contracting stalk was found to be one of the world's fastest cellular engines.

They're Eukaryotes!

Teensy bell animals like this one, Vorticella, also sport a nucleus inside the main body.

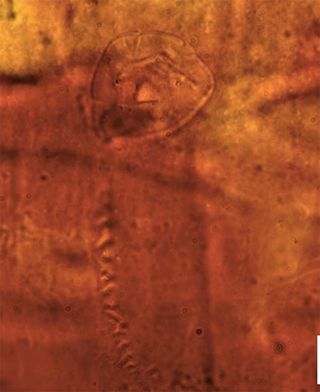

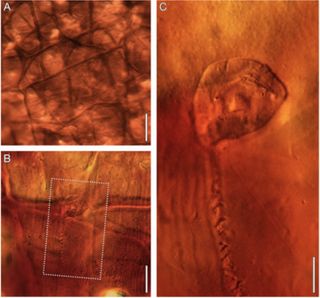

Leech Cocoon

The bell animal was trapped inside a leech cocoon, much like this one.

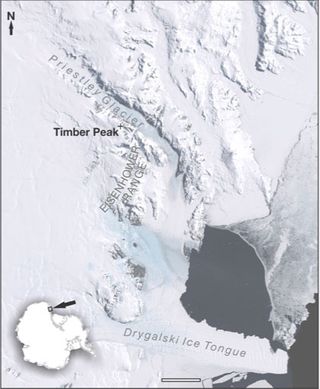

Lush Antarctica?

The cocoon was found in the Timber Peak section of the Transantarctic Mountain Range. When the bell animal was alive, this area would have been a dense rain forest, as Earth was much warmer back then.

Bell Animal

The Triassic Vorticella-like fossil (square in image focuses on the creature encased in cocoon) seen inside the cocoon wall. Like other eukaryotes, the Vortella animal was equipped with a nucleus, in this case a large horseshoe-shape nucleus inside the main body (C).

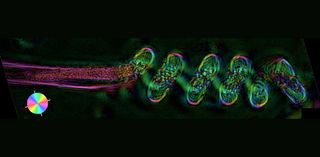

Springy Stalk

Past research has suggested Vorticella's coiled stalk, which is used to attach to substrates, may be one of the fastest cellular engines known, changing from a telephone wirelike structure to a tight coil at a speed of about 8 centimeters per second — the equivalent of a human being walking the across more than three football fields in one second. In that research, MIT's Danielle Cook France and colleague used high-speed microscopes and special chemicals that could freeze the stalk in mid-coil, allowing them to take snap-shots of the stalk (shown here) as it contracted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

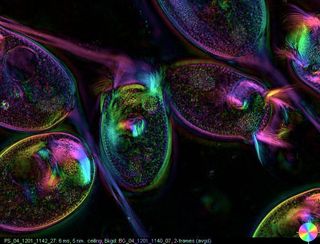

Live Vorticella

Here, live Vorticella visualized using a high-speed microscope developed at MIT.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.