New Fabric Paves Way for Chip-Embedded Clothes

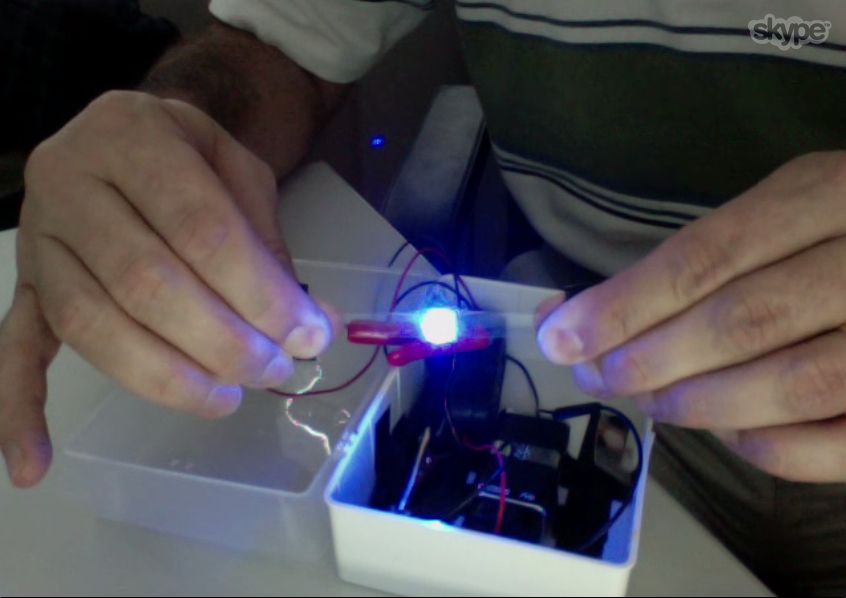

André Studart's new flexible electronic fabric looks like a translucent Band-Aid, except where the pad would be on a bandage, there's a blue LED light.

Studart demonstrated the LED strip for TechNewsDaily over Skype, from his office in Switzerland. He pulled the ends of the strip away from each other, stretching it to several times its original length. The LED, however, didn't stretch. In fact, it can't.

If it's stretched even 1 percent, it would break, Studart explained. "There's a lot of engineering in the material so you protect the electronic device," he said.

Studart, a materials scientist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, and his colleagues solved this challenge by creating this soft, stretchy material that can incorporate stiff parts, such as an LED, and protect those parts from stretching.

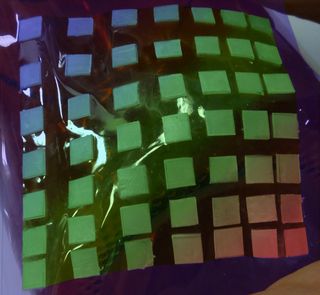

Such high-tech materials could go into clothes with electronics in them, solar panels that can stretch over any surface, and smartphone and tablet screens that users can roll up like a newspaper. Consumers may see the first flexible electronics show up on store shelves in five or 10 years, Studart said.

Inner inspiration

It doesn't seem difficult to stick some silicon chips onto a piece of soft fabric or plastic wrap. The challenge comes in ensuring the electronic-studded fabric stays strong after pulling and stretching. Whenever stiff pieces are incorporated into a softer material, the material is prone to rip right at the edge between soft and hard.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's really an interesting materials challenge," Studart said.

Studart and his colleagues got some of their inspiration from the bones and muscles of the body. Bones are hard and muscles are soft and stretchy, yet they're held together by material (a tendon) that withstands bending and pulling with every move a person makes. [SEE ALSO: Artificial Muscle Is 200 Times Stronger Than the Real Thing]

Tendons are made of collagen, a soft biological material similar to gelatin, which has varying amounts of small mineral platelets in it. The platelets create a continuum of stiffness throughout the tendon that helps it withstand elbow bends and toe-wiggling.

Studart's clear, rubbery, LED-protecting material is also made of a soft base material, called polyurethane, with varying amounts of platelets in it that create a continuum.

"The very important concept that we took from nature is the fact that you have this gradient throughout the material," he said.

In a formal study, Studart and his colleagues found that their tendon-inspired material is able to stretch in one direction to four and a half times its original length without perturbing embedded chips.

Work ahead

Studart still has work to do before stretchy electronic fabrics are reliable enough for everyday use. He still needs to make the material stretchable in all directions, not just one. He'll need to formally test how much stretching the material can take before it rips or breaks. He estimated he has stretched his LED-lit strip about 20 times, but didn't know how many stretches it could really take.

He's also interested in making artificial tendons to replace tendons people may damage, but flexible electronics are likely to make it to market first because there are already companies developing them, he said. He pointed to Cambridge, Mass.-based mc10 as an example.

He and his colleagues published their work today (Dec. 11) in the journal Nature Communications.

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow TechNewsDaily on Twitter @TechNewsDaily, or on Facebook.