Holy Cow! First Cheesemakers Date Back 7,500 Years

The first direct signs of cheesemaking now seen in potsherds from Poland may help reveal how animal milk dramatically shaped the genetics of Europe, scientists reported today (Dec. 12).

Although cheese may just seem to be a topping on pizza or a companion to wine, it may have shaped the evolution of Europeans, researchers say. Cheese evolved after the development of dairy farming, which helped people take advantage of animal milk, a highly nutritious food one can sustainably procure.

Most of the world, including the ancestors of modern Europeans, is lactose intolerant, unable to digest the milk sugar lactose as adults. However, while cheese is a dairy product, it is relatively low in lactose.

"The transformation of milk to a more tolerable product such as cheese for lactose-intolerant people may have helped promote the development of dairying among the first farmers of Europe," researcher Peter Bogucki, an archaeologist at Princeton University, told LiveScience.

In turn, the presence of dairying over many generations may have helped set the stage "for a biological change in Europeans, the evolution about 7,500 years ago in Europe of lactase persistence — that is, keeping the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose, well into adulthood," researcher Richard Evershed, a chemist at the University of Bristol in England, told LiveScience. "This changed Western digestive capabilities." [The 7 Perfect Survival Foods]

History of cheese

The researchers shed light on the origins of dairying by analyzing locales in central Europe once home to the Linear Pottery, or LBK culture, the first known farmers of Europe back in the Neolithic, or New Stone Age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bogucki and his colleagues have worked in this region for more than 35 years, at archaeological sites originally uncovered in the 1930s by farmers digging for gravel.

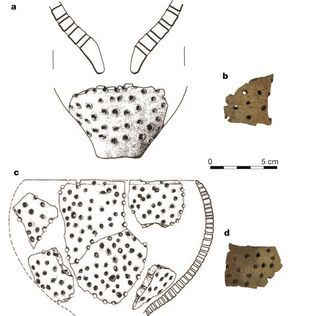

"In the course of excavating these sites, we occasionally came across fragments of pottery with small holes in them," Bogucki recalled. "We realized these were sieves. There weren't many of them, but still a few at just about every site.

"A couple of years later, I was with my wife visiting a friend in Vermont, and I saw these 19th-century agricultural implements, including ceramics that were perforated much like the ones in Poland," Bogucki said. "These were used for cheese manufacturing."

Cheese is made by taking curds of milk and pressing them in cheese strainers, which squeezes out lactose-rich whey, leaving protein- and fat-rich cheese. "It was one of those moments when a light bulb goes off in your head," Bogucki said. "Now it's a long jump from 19th-century Vermont to Neolithic Poland, but we had all this other suggestive evidence of dairying at the sites as well, such as huge amounts of cattle bones."

While those bones may be signs of the people's use of cattle for meat, Bogucki doesn't think that was their main goal, since the farmers lived in a forested region that would've precluded massive cattle ranches. "Cattle takes 42 months to reach maximum meat weight, and cows give birth singly, or rarely in pairs. If all you want is meat, it makes the most sense to do so if you can ranch cattle on a massive scale, such as the plains of the U.S. or Argentina," Bogucki said. [10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Still, these sieves could have conceivably been used to strain anything, such as meat from stock or honeycombs from honey. To see if these ancient hole-laden ceramics were once cheese strainers, Bogucki and his colleagues provided Evershed and his collaborators 50 samples from 34 of these vessels collected over decades from Kuyavia, Poland, dating back 7,500 years. Researcher Melanie Salque at the University of Bristol and her teammates ground up these unglazed potsherds. Chemical analysis of the powder revealing abundant levels of milk-fat residues, suggesting they were used for cheese.

"There isn't a molecule specific to cheese, but when we thought about what other dairy products might require straining, there aren't any other than cheese," Evershed said.

Analyses of other, non-hole-laden pottery at these sites suggested they were not used for processing milk. The presence of carcass fats in cooking pots without holes revealed they were likely used to cook meat, while the presence of beeswax in bottles hinted they might have been waterproofed to store water or other liquids.

Evidence of cheese

Past research had detected milk residues in other sites in northwestern Anatolia about 8,000 years ago and in Libya nearly 7,000 years ago. Still, it was impossible to detect if the milk there was made into cheese.

"The presence of milk residues in sieves, which look like modern cheese-strainers, constitutes the earliest direct evidence for cheese-making," Salque said.

The researchers are uncertain what these ancient cheeses might have tasted like. Still, "these would have been soft cheeses. We don't know if they would've been a Cheddar, Brie or Emmental," Evershed said. "Soft cheese is very easy to make. You just boil some milk up, put in some lemon juice or vinegar, precipitate the curds, and filter it."

The investigators suggest there could also have been cheese-making at earlier times. "They might have used textiles or baskets as cheese strainers," Evershed said. "It's just that those materials don't survive very well in the archaeological record."

The researchers plan to continue to investigate the origins of milking. "This is very closely related to all sorts of other big scientific questions, such as how the interaction of man with animals developed," Evershed said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Dec. 12 in the journal Nature.