SAN FRANCISCO — Though NASA is devoting many of its exploration resources to Mars these days, the agency still has its eye on an icy moon of Jupiter that may be capable of supporting life as we know it.

Last week, NASA officials announced that they plan to launch a $1.5 billion rover to Mars in 2020, adding to a string of Red Planet missions already on the docket. The Curiosity rover just landed this past August, for example, and an orbiter called Maven and a lander named InSight are slated to blast off in 2013 and 2016, respectively.

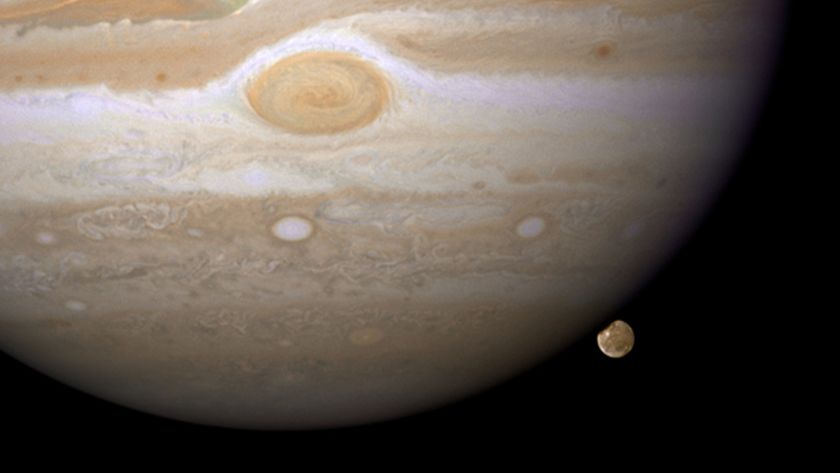

But NASA is also thinking about ways to investigate the possible habitability of Europa, Jupiter's fourth-largest moon. One concept that may be gaining traction is a so-called "clipper" probe that would make multiple flybys of the moon, studying its icy shell and suspected subsurface ocean as it zooms past.

"We briefed [NASA] headquarters on Monday, and they responded very positively," mission proponent David Senske, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said here Dec. 7 at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

The $2 billion unmanned Europa Clipper, which could be ready to launch by 2021 or so, would also do vital reconnaissance work for a potential lander mission in the future, Senske told SPACE.com.

Intriguing Europa

Astrobiologists regard Europa, which is about 1,900 miles (3,100 kilometers) wide, as one of the best bets in our solar system to host life beyond Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

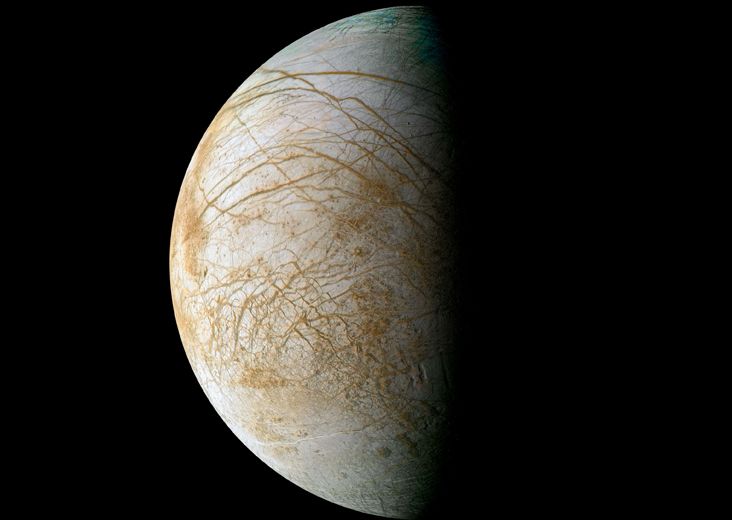

The moon is believed to harbor a large ocean of liquid water beneath its icy shell. Further, this ocean is likely in direct contact with Europa's rocky mantle, raising the possibility of all sorts of interesting chemical reactions, Senske said.

The irradiation of Europa's surface and tidal heating of its interior also mean the moon likely has ample energy sources — another key requirement for life as we know it.

NASA has long been interested in exploring the icy moon and its ocean. Several years back, the agency drew up an ambitious mission concept called the Jupiter Europa Orbiter (JEO), which would have made detailed studies of Europa and the incredibly volcanic Jupiter moon Io.

The science returns from such a mission would have been impressive, according to the 2011 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which outlined the scientific community's goals in the field over the coming decade.

The decadal survey ranked JEO as the second-highest priority among large-scale missions, just behind Mars sample-return. But the report said its $4.7 billion price tag was just too high.

"The recommendation was, immediately go and do a de-scope," said Senske, who was also involved in JEO. "They loved the science; the science was great. But focus it." [6 Most Likely Places to Find Alien Life in the Solar System]

Paring it down

So researchers got to work developing a leaner, cheaper Europa mission that would fit under a firm $2 billion cost cap. They came up with two main options: the clipper and a Europa orbiter (a lander was ruled out as premature).

Because of the intense radiation environment around Europa, the orbiter would have to be heavily shielded, adding weight and cost. Even with this armor, the concept initially called for a nominal design life at Europa of just 30 days, with later versions boosting that up to 109 days, Senske said.

While the orbiter would gather a great deal of interesting and valuable information, it falls short of what the flyby concept could deliver on a dollar-to-dollar basis, Senske said. For example, a $2 billion orbiter would not be able to carry an instrument that could investigate the composition and chemistry of Europa's surface and atmosphere (and, by extension, its ocean).

"In terms of an apples-to-apples comparison, Clipper really does rise to the top," Senske said.

The Europa Clipper

The Clipper would carry a number of scientific instruments, including ice-penetrating radar, a topographical imager, a magnetometer, an infrared spectrometer, a neutral mass spectrometer and a high-gain antenna.

To squeeze all of this gear aboard and still stay under the $2 billion cap, Clipper may need to be powered by solar arrays rather than advanced stirling radioisotope generators as originally envisioned, Senske said. Solar panels are considerably cheaper than ASRGs, which convert the heat from plutonium-238's radioactive decay into eletricity.

NASA's Jupiter-bound Juno probe also sports solar arrays, so there is precedent for sending a solar-powered spacecraft so far from the sun. But a Europa mission would present some additional challenges to address, including eclipses and radiation doses about two times higher than Juno will receive.

"We have some things that we need to test," Senske said.

The Clipper would enter into orbit around Jupiter, then study Europa during dozens of flybys over the course of 2.3 years. On its closest passes, it would come within just 15 miles (25 km) of the moon's frozen surface.

These close encounters should help the probe crack some of Europa's most intriguing mysteries, such as the thickness of its ice shell and the saltiness and approximate depth of its ocean (as well as confirming that the ocean exists), Senske said.

This information, along with the spacecraft's detailed imagery of the moon's surface, could help guide a potential lander mission that would search for signs of Europan life sometime down the road.

The Clipper could probably be ready to launch between 2020 and 2022, Senske said. Its journey to Europa would take about six years.

An uncertain future

The Europa Clipper is not on NASA's books yet, but agency higher-ups and advisory committees both inside and outside the agency have given it high marks thus far, Senske said.

He and the rest of the team will continue developing the mission concept and see what happens.

"In April, we want to do what we're calling a preliminary concept review, start working out the bugs, and then working with headquarters to define when we would have what's known as a mission concept review that would start getting us on the road as a full-up mission," Senske said.

Some scientists who want close-up studies of potentially habitable moons such as Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus were disappointed that NASA selected another Mars rover mission for 2020. But Senske said the agency's mounting successes at the Red Planet — and the public interest missions such as Curiosity have generated — could eventually make more far-flung exploration efforts possible.

"It could potentially be the tide that raises all ships," Senske said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.