Deep Earth Tremors May Foretell Earthquakes

Tiny tremors, smaller than earthquakes, are shaking the Cascadia subduction zone deep beneath the Pacific Northwest.

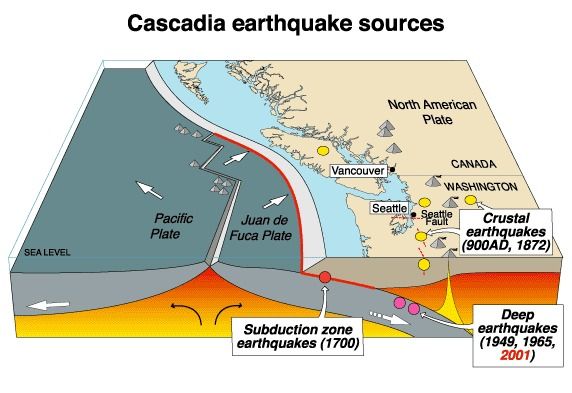

The Cascadia subduction zone is where two of Earth's tectonic plates meet in an epic collision and one haltingly slides below the other. The Cascadia Fault stretches for almost 700 miles (1,100 kilometers) from Northern California up to Canada. The force required to shove a piece of ocean crust into Earth's mantle can produce megaearthquakes along the zone, as in Japan and Sumatra.

But unlike its western Pacific cousins, the Cascadia subduction zone has not experienced a major earthquake since 1700, when an estimated 9.0-magnitude earthquake generated an enormous tsunami that killed trees in Puget Sound and traveled across the ocean to Japan.

The slow-slip and tremors observed in the area are periodic, coming about every 15 months, said Stanford geophysics professor Paul Segall, and were first spotted in 2003. The slow-slip earthquakes creep along the fault at about 4 mph (6.4 kph), for two weeks at a time. The tremors hum about 18 miles (30 km) below Earth's surface, deeper than the zone where big earthquakes rupture. Some scientists think the tremors are evidence of the sinking tectonic plate slowly dropping into the Earth, which may "load" the shallower, locked zone of the fault.

Segall's group uses computational models of the region to determine whether the cumulative effects of many small events can trigger a major earthquake. The research simulates the slow-slip and tremors on a computer model of the subduction zone.

Segall noted that the model needs refinement to better match actual observations on the subduction zone — the decade of intriguing seismic monitoring records that revealed the tremors. He hopes to possibly identify the signature of events that could trigger a large earthquake.

"You have these small events every 15 months or so, and a magnitude-9 earthquake every 500 years. We need to known whether you want to raise an alert every time one of these small events happens," Segall said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We're not so confident in our model that public policy should be based on the output of our calculations, but we're working in that direction," he said.

The results were presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.