Alan Alda: Scientists Should Learn to Talk to Kids

What is time?

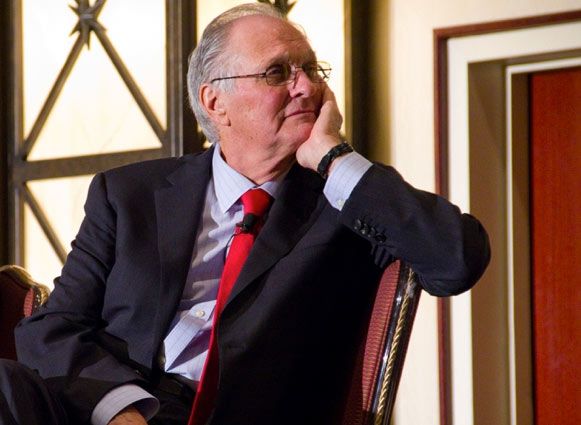

That's the question put to scientists this year by the Flame Challenge, a contest first conceived by actor Alan Alda, famous for his roles on the TV shows M*A*S*H and "The West Wing." The directive? For scientists to explain this complex concept in ways that will inspire and interest 11-year-old children.

The Flame Challenge gets its name from last year's inaugural competition, which posed a question from Alda's own childhood: What is flame? As an 11-year-old, Alda had asked a teacher this question and gotten back the baffling, one-world answer, "oxidation."

Now scientists will face an arguably bigger challenge in explaining the concept of time. Kids will judge the entries, which are due by March 1. (Teachers must apply for their classrooms to become judges by Feb. 1.) Creativity is encouraged: Last year, the winner explained flame with not only an animated video, but also with an originally composed song.

Alda talked with LiveScience about the sophisticated minds of 11-year-olds, his own interest in science and why scientists should learn to talk to kids.

LIveScience: How did you get interested in science communication?

Alda: I think my interest began when I was actively involved in helping communicate science when I was doing "Scientific American Frontiers" and other science shows on PBS. Accidentally, we discovered an unusual way to do science communication, which was through conversations with scientists rather than asking a set bunch of questions that had predictable answers. What we did was get into a real conversation where I didn't know what the answers were going to be. I didn't even know what the questions were going to be. [What's That? Your Basic Physics Questions Answered]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What happened was the scientists, in pretty much every case, came out from behind lecture mode and got personal, because they really wanted one person to understand, which was me. When I finally did understand it, it often became a little television moment where the audience saw an event take place, and it made it easier for them to understand it, too.

In the course of that, I began to think, wouldn't it be wonderful if scientists had this ability to engage in a personal dialogue with the public like this without somebody like me having to be there for it?

LiveScience: What's the goal of the Flame Challenge?

Alda: I'll tell you what it looks like it is and what it actually is. It looks like it's a way to teach 11-year-olds science, and what it really is is a way to get scientists to experience how hard it is to say something that they know so well in a way that an 11-year-old can understand it, so that they get challenged by the difficulty of it, and, we hope, want to look further into communicating hard stuff more simply.

What's interesting about it is that the kids are so excited about being the judges of these entries. They get a chance for the first time, somebody their age, to judge the work of somebody the scientist's age. They're very serious about it, they're not flippant at all. In the first year's round a very common complaint was that the entries weren't informative enough. They don't just want entertainment, they want information. [Gallery: Science Meets Art]

LiveScience: What's the advantage of gearing the answers toward kids rather than adults?

Alda: That just happened by accident. The way this came about, I was asked to write a guest editorial for the journal Science about communicating science. I can remember the chair I was sitting in where I was working on it, and I remember thinking, "I'm writing something anybody could write."

Everybody knows all these reasons we need good communication. It suddenly occurred to me, wait a minute, I have a very vivid story of poor science communication. It was when a teacher gave me a one-word answer to a question. I was so fascinated by what flame was, and I asked this teacher and she said, "Oxidation."

It became a real springboard for action. What happened is that more than 800 scientists around the world contributed entries [last year], and more than 6,000 kids around the world became judges, including an aboriginal classroom in Australia. They were from all over.

This is purely anecdotal, but 11 seems to be an age where you can formulate tough questions, and you can assimilate the answers to those questions. But it also turns out that if an answer makes sense to kids, it's going to make sense to most of the rest of us, too.

LiveScience: This year's question seems much tougher.

Alda: It's way tougher, and it makes me think that 11-year-olds have grown in sophistication since I was an 11-year-old. I asked about something you could see and feel the heat from and you could read by. It was there. But now these kids are asking —"What is time?" — which you can keep track of with a clock or the change of seasons, but what it actually is is an extremely deep question that I think a lot of people have tried to answer unsuccessfully.

It'll be really interesting to see how scientists approach this answer. I think it has to be satisfying on the sense that it gives you a handle in the underlying depth of the question and maybe gets you interested in exploring it further. I think it would be a very successful answer if all it does is get a couple of kids interested in devoting their lives to that question.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappasor LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook& Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.