Just like people, huge star clusters age at variable rates depending on their lifestyles, a new study reports.

While such star clusters are many billions of years old, some of them manage to stay young at heart while others speed along toward decrepitude, astronomers found.

"By studying the distribution of a type of blue star that exists in the clusters, we found that some clusters had indeed evolved much faster over their lifetimes, and we developed a way to measure the rate of aging," lead author Francesco Ferraro, of the University of Bologna in Italy, said in a statement.

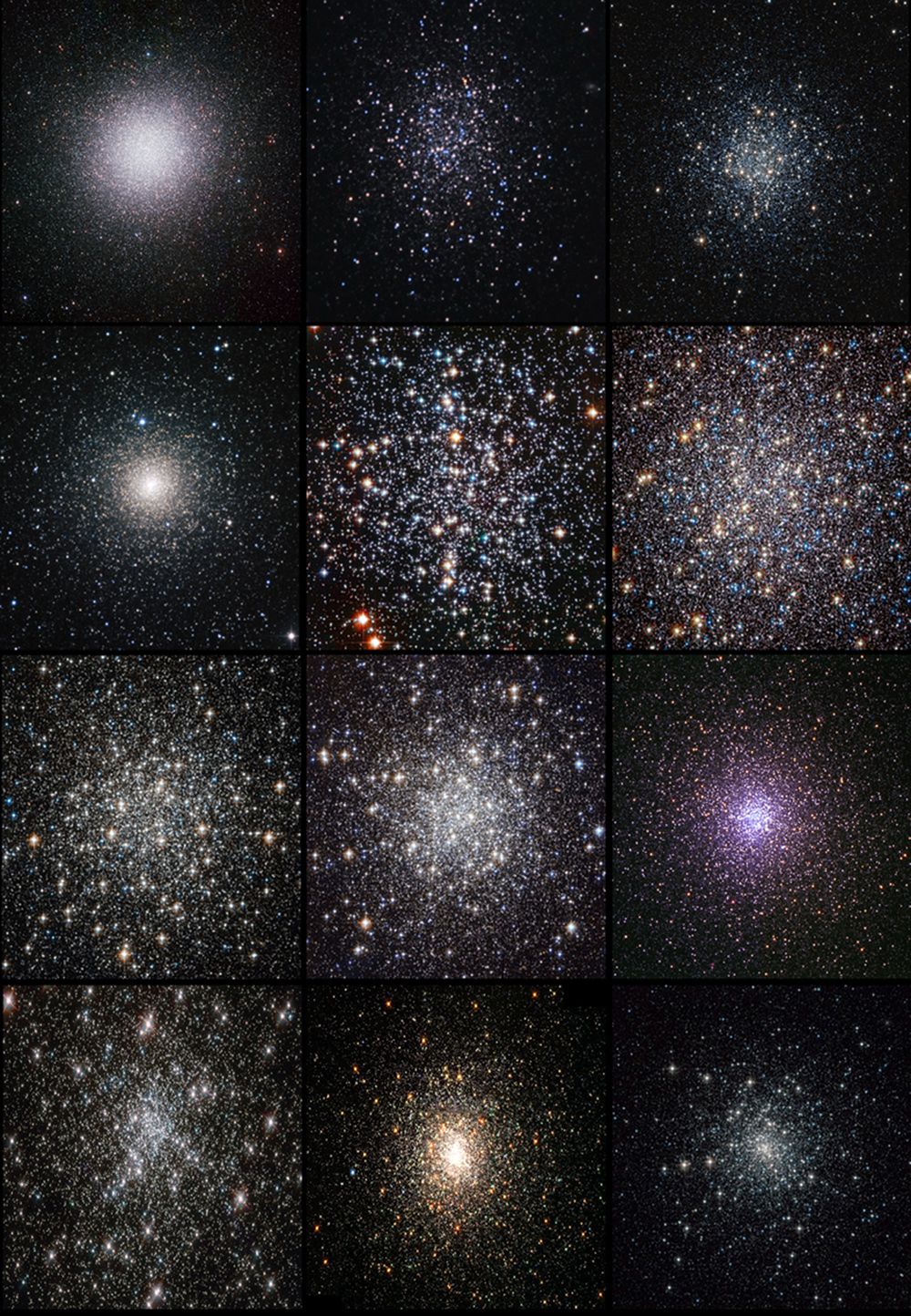

Ferraro and his colleagues used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and several ground-based instruments to study 21 globular clusters scattered throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

Globular clusters are spherical collections of hundreds of thousands of stars held together by gravity. The 21 clusters examined in the new study all formed more than 10.5 billion years ago — not too long after the Big Bang, which created our universe 13.7 billion years ago.

The team focused on so-called "blue stragglers" within the clusters — stars that are much bigger and brighter than their ages should allow (since large, luminous stars tend to burn out quickly). Astronomers think blue stragglers get reinvigorated by sucking matter from, or colliding with, neighboring stars.

Because blue stragglers are so massive, they tend to sink toward the center of clusters over time, just as heavier sediments settle at the bottom of a river or lake. But the new study suggests that this process occurs at different rates from cluster to cluster.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A few clusters had blue stragglers distributed throughout, making them appear young. Some seemed old, with the stragglers already clumped in the center. And others were somewhere in between.

"Since these clusters all formed at roughly the same time, this reveals big differences in the speed of evolution from cluster to cluster," said co-author Barbara Lanzoni, also of the University of Bologna. "In the case of fast-aging clusters, we think that the sedimentation process can be complete within a few hundred million years, while for the slowest it would take several times the current age of the universe."

The study was published online today (Dec. 19) in the journal Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.