Spiral Dust Clouds May Reveal Alien Planets

Astronomers may have found a way to detect alien worlds embedded in rings of dust around distant stars.

Newborn stars often have clouds of leftover gas and dust around them that condense into rings called protoplanetary disks. Eventually, under the pull of gravity, the material in these disks may clump together to form orbiting planets.

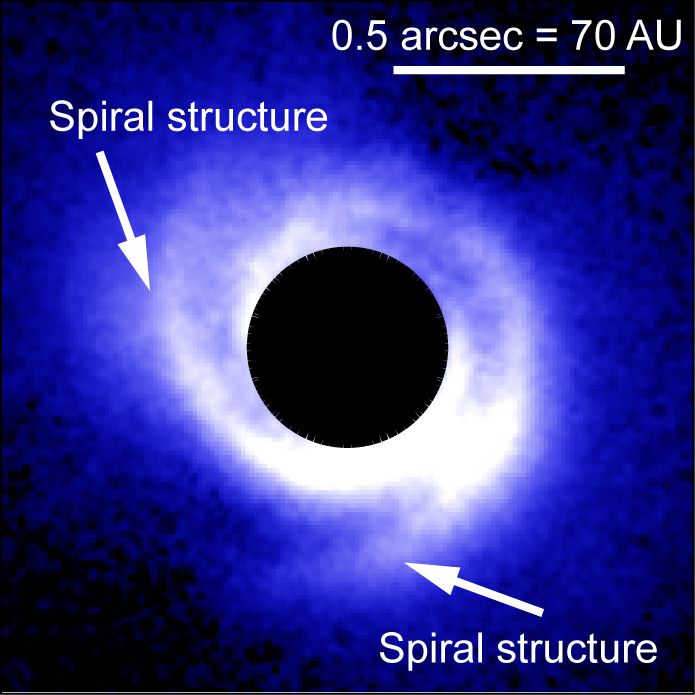

A team of astronomers captured detailed images of the disk around young star SAO 206462, about 460 light-years away in the constellation Lupus. For their observations, they used the HiCIAO camera on Japan's Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, which is designed to block out harsh central starlight that would normally make it difficult to detect fainter nearby objects, such as a disk around a star.

The disk around SAO 206462 is an impressive 12.4 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) in radius, a distance about five times larger than Neptune's distance from our sun. The disk also has a spiral structure with two clear arms curving along the outer region, the scientists discovered, and theory suggests planets could be the culprit behind that shape.

Researchers do not have the capacity to directly observe planets around a star like SAO 206462. But according to density wave theory, a rotating disk of matter should develop a wave-like concentration of dense material because the outer and inner parts of the disk rotate at different rates. This dense region would eventually grow into a spiral. The researchers think such a process could have been set off around this 9-million-year-old star by planets lodged in its disk.

"This is the first time that density wave theory has been applied to measuring the features of a protoplanetary disk," officials with the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan said in a statement Monday (Dec. 19). "The research takes an important step in explaining how a spiral disk could form and may mark the development of another indirect means of discovering planets."

The research was detailed in the Astrophysical Journal Letters in April 2012.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.