Moon May Outshine Quadrantid Meteor Shower Tonight

One of the best displays of "shooting stars" will peak overnight tonight and early Thursday morning (Jan. 3), but unfortunately will run into some stiff competition this year from a bright moon.

The celestial fireworks display is the Quadrantid meteor shower (pronounced KWA-dran-tid), which kicks off the annual meteor shower schedule every January.To paraphrase Forrest Gump: The Quadrantids are like opening up a box of chocolates; you never know what you're going to get! Indeed, the "Quads" are notoriously unpredictable.

This year, the meteor shower is peaking while the moon is in its bright gibbous phase, just days after the recent full moon on Dec. 28, which may interfere with the cosmic light show.

The Quadrantids provides one of the most intense annual meteor showers, with a brief, sharp maximum lasting but a few hours. Adolphe Quetelet of Brussels Observatory discovered the shower in the 1830's, and shortly afterward it was noted by several other astronomers in Europeand America. [Amazing Quadrantid Meteor Shower Photo of 2012]

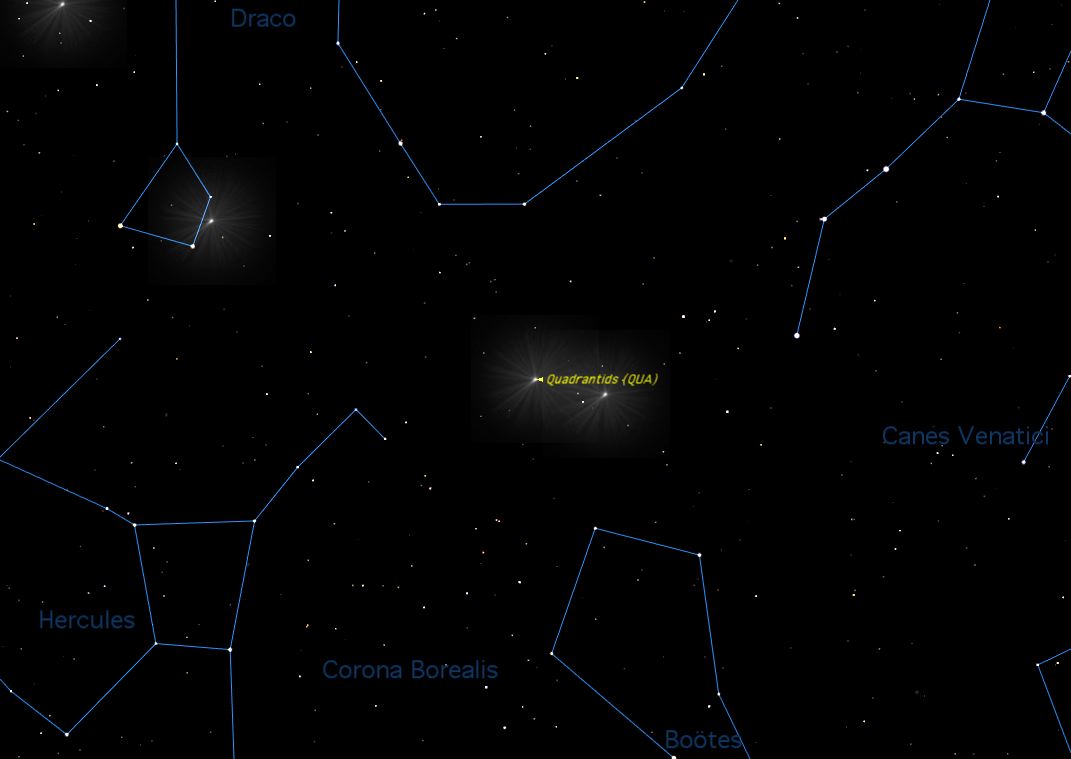

The meteors are named after the obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis the Mural or Wall Quadrant (an astronomical instrument), depicted in some 19th-century star atlases roughly midway between the end of the Handle of the Big Dipper and the quadrilateral of stars marking the head of the constellation Draco. (The International Astronomical Union phased out Quadrans Muralis in 1922.)

NASA will provide a live webcast of the 2013 Quadrantid meteor shower each night this week through Friday (Jan. 4). You can follow the meteor shower on SPACE.com here courtesy of the NASA feed.

Difficult to see

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unfortunately, many factors combine to make the peak of this display difficult to observe on a regular basis:

A brief peak period: The Quadrantids’ meteor rates exceed half of their highest value for only about six hours (compared to two days for the Perseid meteor shower in August). This means that the stream of particles that produce this shower is a narrow one — apparently originating from a small comet within the last 500 years.

The parentage of the Quadrantids had long been a mystery until astronomer Peter Jenniskens, a meteor expert with the SETI Institute at Mountain View, Calif., noticed that the orbit of 2003 EH1 — a small asteroid discovered in March 2003 — ''falls snug in the shower.'' He believes that the 1.2-mile-wide (2 kilometers) asteroid is the source of the Quadrantids. The asteroid, in turn, is possibly the burnt out core of the lost comet C/1490 Y1. [Quadrantid Meteors in the Night Sky (Video)]

You have to be an early-bird (or extreme night owl): As viewed from mid-northern latitudes, we have to get up before dawn to see the Quadrantids at their best. This is because the radiant (the part of the sky from where the meteors to appear to originate) is down low on the northern horizon until about midnight, rising slowly higher as the night progresses. The growing light of dawn ends meteor observing usually by around 7 a.m. So, if the "Quads" are to be seen at all, some part of that eight-hour active period must fall between 2 a.m.and 7 a.m.

It’s winter in the north: Over northern latitudes, early January often sees inclement or unsettled weather.

The moon interferes: In one out of every three years, bright moonlight spoils the view and unfortunately, 2013 is one of those years. According to British meteor expert Alastair McBeath: "The waning gibbous moon causes severe problems for detailed observations of the Quadrantid maximum in 2013."

It is not surprising then, that the Quadrantids are not as well-known as some of the other annual meteor showers.

Quadrantid meteor shower viewing tips

According to Robert Lunsford of the American Meteor Society, here is what to expect during the Quadrantid meteor shower’s peak: "A bright gibbous moon (will be) located near the Leo-Virgo border. Activity can be still seen from the Quadrantids if your skies are clear and transparent. It would also be wise to keep the moon out of your field of view by facing the north to east quadrant of the sky."

In 2013, Western North Americawill be favored to view of the peak of the Quadrantids. Maximum activity this year is expected on Thursday morning, Jan. 3 at 5 a.m.Pacific Standard Time. For those in the western United States, the meteor shower's origin radiant will be about two-thirds of the way up in the east-northeast sky.

The farther to the north and east you go, the higher in the sky the radiant will be. To the south and west the radiant will be lower and the meteors will be fewer.

Quadrantid meteors are described as bright and bluish with long silvery trains. As McBeath and Lunsford have pointed out, the moon's presence will make seeing the maximum number of meteors problematic. Without the bright moon, western observers likely would see as many as 60 to 75 meteors per hour; a very dark sky might even yield 100 or more per hour.

But this year, the moon will be the big obstacle. For every magnitude of naked eye stars hidden by moonlight or light pollution, the number of meteors is cut by roughly 60 percent.

You can check how bright your moonlit sky is by looking for the Little Dipper star pattern. The four stars in the bowl are of magnitudes 2, 3, 4 and 5 (the lower the number, the brighter the star). So, if you can see only three of the four stars in the bowl, your limiting magnitude would be 4, meaning you would see only about one-tenth the meteors you would if you were under a very dark, moonless sky.

Quadrantid meteor rates will be lower across the central and eastern United States, as well as other places north of the equator where the peak of the shower will occur either after sunrise or with the shower radiant very low in the sky. Observers south of the equator will have little chance of seeing any "Quads" since the radiant will not clear the horizon before morning twilight interferes.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing photo of the Quadrantid meteor shower and would like to share it with SPACE.com, send images and comments, including name, location and equipment used to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.