Giant Gas Geysers Erupting from Milky Way Galaxy

Colossal magnetized fountains of gamma-ray-emitting gas are spewing from the center of our Milky Way galaxy, researchers say.

The amount of magnetic energy contained in these geyser-like outflows "corresponds to the energy liberated by about a million supernova explosions — that is a lot!" study lead author Ettore Carretti, an astrophysicist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia, told SPACE.com.

These outflows could help solve mysteries concerning the magnetic field of the Milky Way galaxy, Carretti added.

Past research detected regions, later called "Fermi bubbles," that emitted gamma rays far above and below the galactic center. Gamma rays are the most energetic form of light.

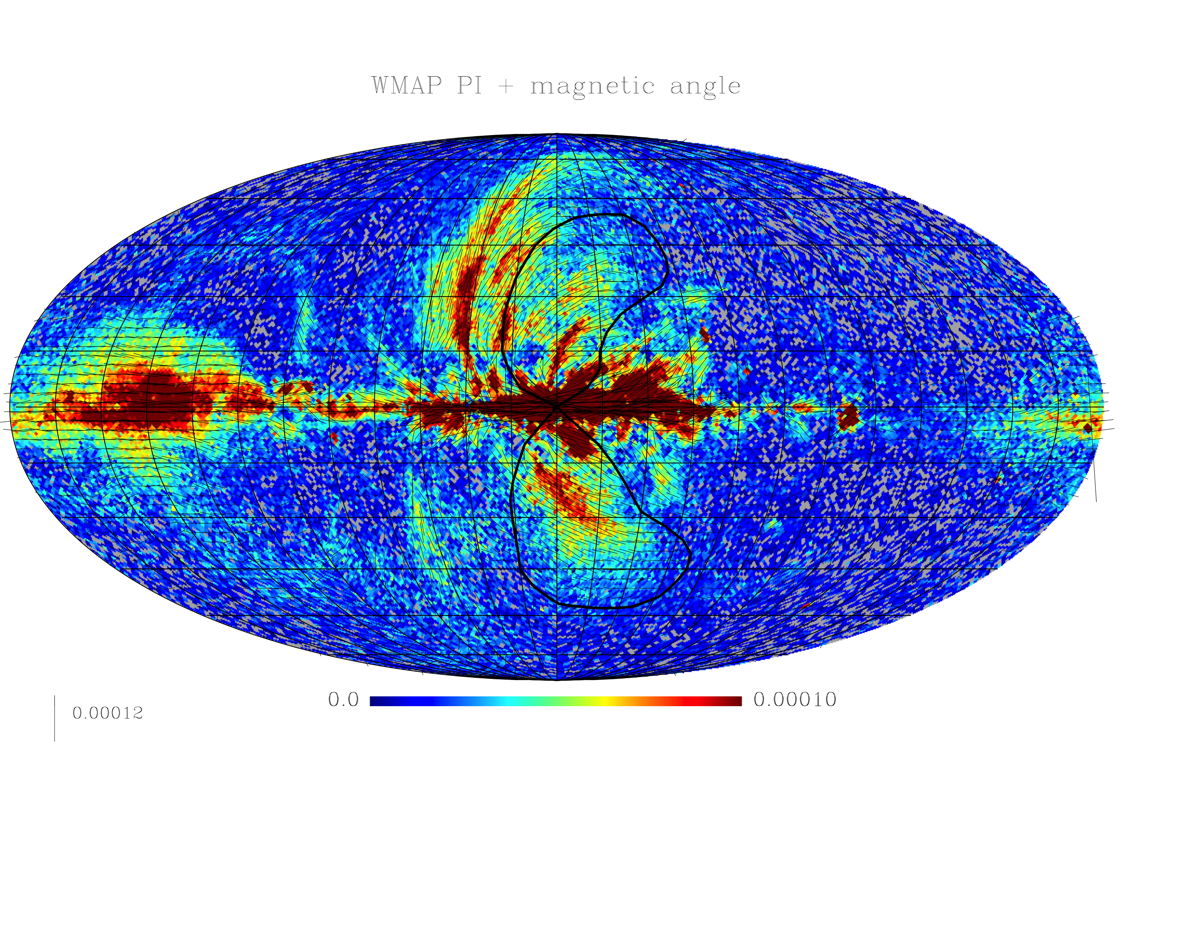

To learn more about these Fermi bubbles, the researchersanalyzed the parts of the sky including these regions using the Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia as part of the S-band Polarization All Sky Survey (S-PASS). They detected giant outflows of gamma-ray-emitting gas, two cone-shaped lobes that combined are about 50,000 light-years long.

"That is about half the size of the entire Milky Way," Carretti said. Seen from Earth, the outflows stretch about two-thirds across the sky from horizon to horizon.

Each of these lobes is about 13,000 light-years wide, and made of gas traveling about 2.2 million mph (3.6 million kph). [Amazing Milky Way Photos]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Beside the galactic disc, these are the largest structures ever discovered in our galaxy," Carretti said.

These outflows are about 100 million years old, and apparently spew mostly from supernovas within the compact 650-light-year-wide area surrounding the supermassive black hole at the core of the Milky Way. Supernovas are the most powerful exploding stars in the universe, bright enough to momentarily outshine their entire galaxies.

"The compact region around the Milky Way's center harbors the most active star formation activity of our galaxy, and a number of supernova episodes occur there," Carretti said.

These outflows each hold a vast amount of magnetic energy, which helps explain why they glow with gamma rays.

"The gas expelled by supernova explosions is magnetized," Carretti said. "Moreover, all of the area of the galactic center possesses a strong magnetic field and the outflows, made of charged particles, can trap the magnetic field they are immersed in.

"These findings tell us there is transport of a massive amount of energy and strong magnetic fields from the galactic center to the outskirts of the galaxy," Carretti said. "It is an interaction we did not know about, and can transform our view of the galactic halo."

The galactic halo "was supposed to be a quiet place," Carretti said. "We now know it is continuously fueled with a massive amount of energy."

These cone-shaped outflows have denser ridges corkscrewing around their surfaces much like strings of lights wrapped around Christmas trees. These ridges are about 13,000 to 16,000 light-years long and 1,000 light-years wide.

"They are made of relativistic charged particles — high-energy particles that move nearly at the speed of light," Carretti said.

One of these ridges, dubbed the Galactic Center spur, apparently stems from a super-stellar cluster orbiting the galaxy's center. Super-stellar clusters contain a very large number of young, massive stars.

These ridges take on a corkscrew form because matter spewing out from the spinning center of the galaxy moves in spirals. This is because of conservation of angular momentum, the same property that causes ice skaters to spin faster if they draw their arms in.

The other two ridges the researchers see are not connected to super-stellar clusters. The researchers suggest the clusters they originated from may no longer be active, thus shedding light on the history of star activity in the galactic core.

These outflows might help explain mysteries surrounding the galaxy's magnetic field.

"How the galactic magnetic field is generated and sustained is still a mystery, and our finding can be crucial to solve it," Carretti said. The outflows carry magnetic material from the galactic center to the galactic halo, helping to explain why a magnetic field pervades the galaxy, he said.

As monstrous as these outflows are, they are no danger to us, Carretti said. "They are not coming in our direction, but go up and down from the galactic plane. We are 30,000 light-years away from the galactic centre, in the plane," he explained in a statement.

In the future, the researchers would like to identify the roots of the outflows and their ridges and investigate any connections between the magnetic fields of the outflows and the galaxy's.

The scientists detailed their findings in tomorrow's (Jan. 3) issue of the journal Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.