Shake It! Dinosaurs Waggled Flashy Tails to Woo Mates

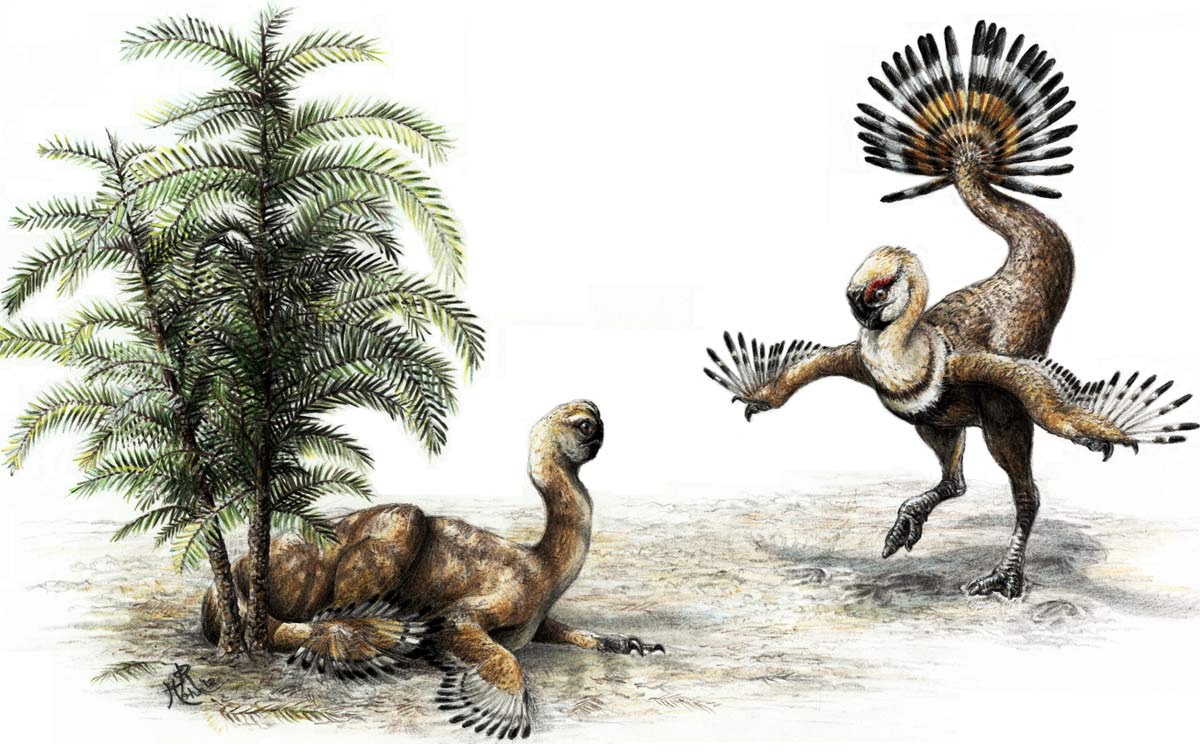

Feathered dinosaurs might have used muscular tails to shake tail feathers and lure the opposite sex, researchers say.

Scientists analyzed 75-million-year-old fossils of feathered, two-legged dinosaurs known as oviraptors retrieved during expeditions to the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. Although oviraptors were members of the meat-eating theropods, making them relatives of such fearsome predators as T. rex and Velociraptor, most oviraptors had beaks that lacked teeth.

"There are good reasons to think they had gone vegetarian," researcher Scott Persons, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Alberta in Canada, told LiveScience. "They were odd ducks, strange dinosaurs," said Persons, who presented the study results at the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology's annual meeting in November, but only this week were they published in a scientific journal.

Past research had revealed oviraptors often had eye-catching bone crests on their heads. "Now we know there was something funny going on at the other end, too," Persons said.

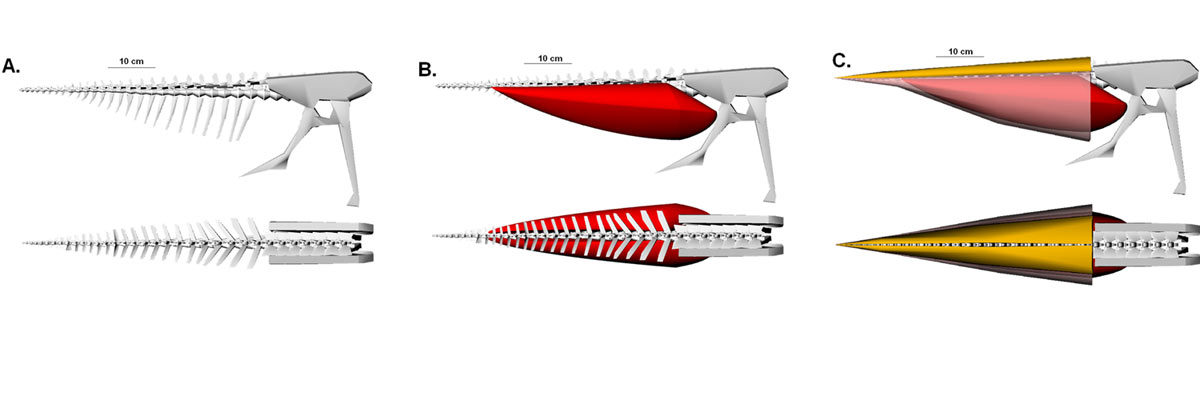

Oviraptor tails were short, but were made of many tailbones, with many points between these vertebrae where they could flex. Persons and his colleagues found oviraptor tailbones also had many projections onto which muscles could attach. Computer models estimating the size of these muscles based on oviraptor skeletons suggest these muscles were quite large. [Paleo-Art: Stunning Illustrations of Dinosaurs]

"Their tails were not only very, very flexible, but quite muscular," Persons said. "They could not only move them sinuously to strike a pose, but also hold it to do a muscular dance with the tail."

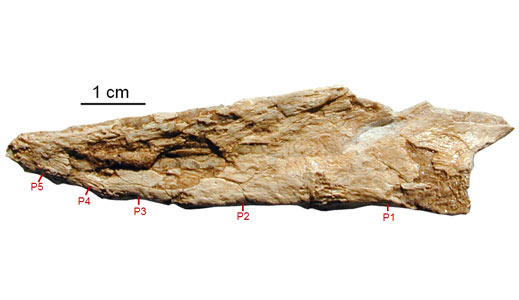

Unusually, at the very end of the tail, "in some oviraptors, the last few vertebrae were actually fused together to become one solid, ridged, bladelike structure," Persons said. "The only other kind of animal where you see that are modern-day birds, where it's called a pygostyle, which serves as an anchor point for a big fan of tail feathers."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Modern-day birds use pygostyles to help them fly, "but oviraptors were not flying animals — they had feathers, but they didn't have big broad wings," Persons said. "What else are pygostyles used for? Peacocks and turkeys use their tail feathers for courtship displays."

Past research has suggested that dinosaurs may have first evolved feathers for show, not flight. Persons and his colleagues found that at least four known oviraptor species separated by 45 million years had pygostyles.

"I think like peacocks, oviraptors were strutting their stuff by shaking their tail feathers to show off," Persons said. "Between the crested head and feathered-tail shaking, oviraptors had a propensity for visual exhibitionism."

Although feathers on dinosaur forearms might have served as stabilizers that helped them steer, that may not have been the case for any tail plumes. "Flightless birds such as ostriches and emus don't have big tail-feather fans, and birds that do have big tail-feather fans such as peacocks and turkeys don't try to use them to run at all, but just keep them tucked in except when fanned out for display."

In the future, Persons and his colleagues want to see if such tails were typically found in one sex or the other. "Maybe they were larger in males, as we see in modern-day birds," Persons said. "The problem there is that the tip of the tail is one of the rarest parts of a fossil skeleton to find, so it might be hard to discover evidence of these sexual differences."

Persons and colleagues Philip Currie and Mark Norell detailed their findings in the Jan. 4 issue of the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.