Songbird's Voice Box Modeled in 3D

Songbirds can create a vast array of sounds, but researchers aren't completely clear on how. Now, they've taken a step toward understanding the process with a new three-dimensional model of a songbird's voice box.

Like humans, birds learn to create species-specific, complex sounds that they can reproduce at will. Birds can even change their songs, with females often responding more enthusiastically to hot new hits tweeted by other birds compared with the oldies. And, said study researcher Coen Elemans of the University of Southern Denmark, birds make all this music while in motion.

"Just imagine an orchestra musician playing his instrument while performing a dance," Elemans said in a statement. "How do birds do this?"

The vocal organ of songbirds is called the syrinx. It's located right at the spot where the windpipe forks and heads toward the lungs.

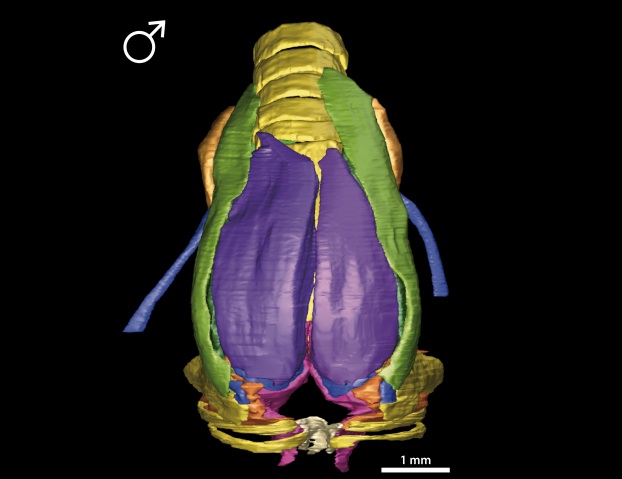

Researchers' understanding of the syrinx's function is incomplete, Elemans and his colleagues wrote today (Jan. 8) in the journal BMC Biology. So the scientists used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and microscope-aided dissection to reveal the inner workings of the syrinx of the zebra finch, the most common bird used for studies of birdsong.

Using that data, the researchers created a 3D model of the organ, including its soft tissue, cartilage and muscle attachments.

The results are a basis for future experiments on how finches and other songbirds create complex sounds, Elemans said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We show how the syrinx is adapted for superfast trills and how it can be stabilized while the bird moves," he said. "Also we emphasize how several muscles may work together to control for example the pitch or volume of the sound produced "

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.