China's Potential Anti-Satellite Test Sparks US Concern

Reports that China may be on the verge of carrying out another anti-satellite test soon are ringing alarm bells among U.S. space policy and military analysts.

That “strong possibility” was noted by Gregory Kulacki, senior analyst and China project manager for the Union of Concerned Scientists Global Security Program, in a Jan. 4 posting on the UCS website blog, All Things Nuclear - Insights on Science and Security.

“It is not clear what kind of test may be planned, if indeed one is in the works,” Kulacki wrote.

Kulacki flagged the fact that, for several months, rumors have been circulating within the United States defense and intelligence communities that a Chinese anti-satellite test is imminent. It might be conducted on Jan. 11, the date on which China performed ASAT operations in both 2007 and 2010.

“Our hope is that getting this out in the open can facilitate a meaningful bilateral dialogue on space security, or, at the very least, get the Obama administration to explain why it refuses to talk to the Chinese about their plans to test,” Kulacki told SPACE.com.

If indeed a China ASAT test is on the horizon, what about potential U.S. reaction? SPACE.com asked several experts to comment on this prospect:

What type of target?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“The condemnation that accompanied China’s first ASAT test was more because of the debris it created, not because it was an ASAT test. The second ‘ASAT test’ hardly sparked a ripple,” said Marcia Smith, a respected space policy analyst and editor of SpacePolicyOnline.com. [10 Most Destructive Space Weapon Concepts]

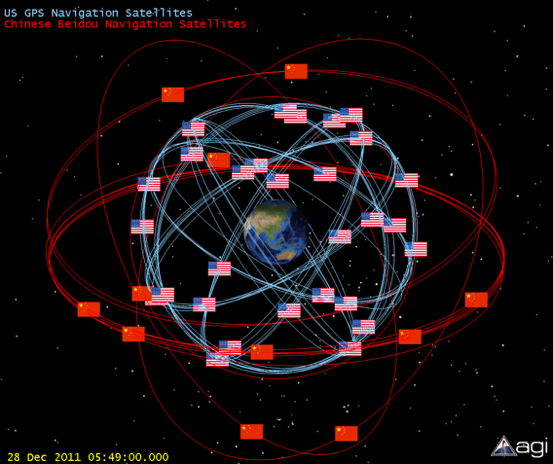

“I think the reaction to the next one, whenever it is, will depend on what type of target (low-Earth orbit, medium-Earth orbit — e.g. Global Positioning System satellites) it threatens and whether it is conducted to avoid creating long-lived debris,” Smith said.

This all assumes that, if it is targeted against a satellite, it is one of China’s own satellites,” Smith said. “If there is any inkling that it is aimed at another country’s satellite…that, of course, would be an entirely different matter.”

Potential space catalyst

Smith said she continues to believe that China’s space activities are aimed more at regional than global leadership.

“Other countries in the region may react quite differently than the U.S., especially since they just experienced the North Korean missile/satellite launch,” Smith said.

“It is easy to imagine they would view this as an escalation of militaristic ambitions in space and a potential catalyst to development of their own ASAT capabilities,” Smith said.

Adding his voice to the discussion is James Clay Moltz, a national security affairs associate at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

“It seems that China's military and political/scientific/commercial bodies have been at odds since 2007 about defining appropriate uses of space," Moltz said.

The People’s Liberation Army, for example, Moltz said, “has largely ignored principles enunciated by its foreign ministry. But if China’s new political leadership fails to rein in the military on future space weapons tests, it is going to further stimulate military space activities among its neighbors — such as India and Japan — and foment tensions with the United States.”

If this occurs, Moltz said, “China will have itself to blame. It will also have a much harder time trying to convince others of its peaceful intentions in space.”

Discouraging ASAT tests

“If the intelligence communities have any real sense that the Chinese are thinking of testing an ASAT again, the U.S. ought to do everything it can to discourage them from doing so,” said Joan Johnson-Freese, a national security affairs professor at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, R.I.

Johnson-Freese told SPACE.com that Kulacki’s Internet posting points out several key elements, noting that the opinions she is expressing are her own and do not reflect the views of the U.S. government, the Department of the Navy, or the Naval War College.

Johnson-Freese said that in 2007— though the U.S. was aware of precursor tests before the eventual test when impact occurred, creating dangerous amounts of space debris— the U.S. said nothing. By taking that action, she said, perhaps that gave a false signal of assent to Chinese decision-makers. “There should be no ambiguity regarding U.S. objections in the future.”

Technical and political calculations

Johnson-Freese said that if the Chinese do another test, they may again call it a missile defense test, as they did in 2010 — and the U.S. and India have done at other times — “because of basically symbiotic technologies involved, evidencing the challenges posed by dual-use technology and how those technologies can generate global security dilemmas.”

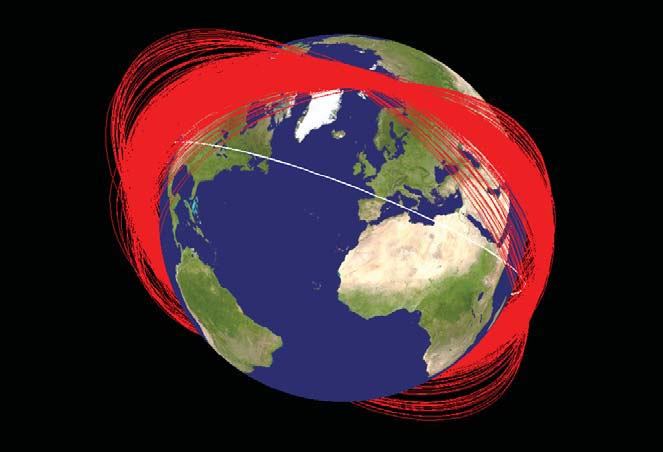

China — and all other countries — have become acutely aware of the dangers of space debris, especially since the reckless 2007 Chinese test, Johnson-Freese said.

“China has had to maneuver some of its own space assets to avoid potential collisions with debris it created,” Johnson-Freese said. “Therefore, it might be hoped that whatever they do, they will consider the debris issues in their technical and political calculations.” [Growing Threat of Space Debris (Video)]

Needed: bilateral discussions

Johnson-Freese pointed out that China is weighing its options with regard to potentially signing a space Code of Conduct in the future, which would demonstrate that China is ready to be a responsible member of the family of spacefaring nations.

“An ASAT test that created more space debris would certainly go against their professed desire to be considered as such a responsible nation,” Johnson-Freese said.

“As long as Congress continues to block bilateral discussions between the U.S.-China on potential civilian space-cooperation projects, the likelihood of much needed U.S.-China discussions on space security issues will be small, or nonexistent. The counterproductive nature of those congressional bans should be reconsidered for a variety of geostrategic reasons,” Johnson-Freese said.

Space code of conduct

Also reacting to the possibility of a Chinese ASAT test is Michael Krepon, co-founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Stimson Center and director of the South Asia and Space Security programs.

Krepon’s work on space security centers on the promotion of a Code of Conduct for spacefaring nations.

“A number of states, including China, the United States and India, have employed ballistic missile defense tests to become smarter about ASAT applications,” Krepon told SPACE.com. “Additional tests of this nature that do not have long-lasting debris consequences would be unwelcome, but not surprising. These tests would serve to ratchet up ASAT capabilities elsewhere,” he said.

Krepon said that another Chinese ASAT test that generates long-lasting debris, at whatever orbit, “would be irresponsible and dangerous for all spacefaring nations, raising the risk of catastrophic loss to satellites and human spaceflight.”

A second test of this kind by the People’s Liberation Army “would demonstrate that the Chinese leadership has learned nothing from the first one,” Krepon concluded.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.