What is the Gulf Stream?

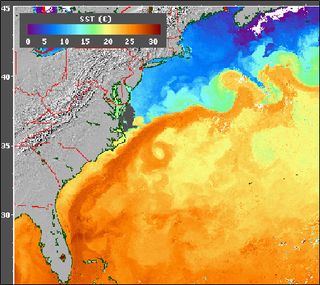

The Gulf Stream is a powerful current in the Atlantic Ocean. It starts in the Gulf of Mexico and flows into the Atlantic at the tip of Florida, accelerating along the eastern coastlines of the United States and Newfoundland. It is part of the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, one of the five major oceanic gyres, which are large systems of circular currents and powerful winds.

The Gulf Stream is a western boundary current; its behavior is determined by the North American coastline. Trade winds from Africa drive water in the Atlantic westward until it hits the coastline and gets pushed northward. In turn, the Gulf Stream affects the climate of the areas closest to the current by transferring tropical heat toward the northern latitudes. There is a consensus among scientists that the climate of Western and Northern Europe is warmer than it would be otherwise because of the North Atlantic Current, one of the branches of the Gulf Stream. [Video: Animation Reveals Ocean Currents]

Early discoveries

The first mention of the Gulf Stream can be traced to the 1513 expedition of Juan Ponce de León. On April 22, 1513, he wrote in his voyage log: "A current such that, although they had great wind, they could not proceed forward, but backward and it seems that they were proceeding well; at the end it was known that the current was more powerful than the wind."

Explorers Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert also made note of the powerful Gulf Stream, and it became widely used by Spanish ships sailing from the Caribbean to Spain.

Six years after Ponce de León's notation, Anton de Alaminos set sail for Spain from Vera Cruz, Mexico, using the Gulf Stream, following the Florida coastline northward before turning eastward to Europe. He had served as the chief pilot aboard Ponce de Leon's ship on his earlier trip and had also sailed with Columbus on his last voyage. Some historians credit Alaminos with the discovery of the Gulf Stream because he was the first to take advantage of it.

Hernando Cortez was perhaps the first to send large numbers of ships from Mexico northward through the Florida Straits, then eastward following the clockwise motion of the Gulf Stream to return to Spain.

Streamlining colonization

Because it altered sailing patterns and shaved time off a typically long and treacherous trip, the Gulf Stream was instrumental in the colonization of the Americas. Most voyages to Virginia southward chose the southern route across the Atlantic even though it was 2,000 miles to 3,000 miles out of the way. Most return voyages to Europe took advantage of at least part of the Gulf Stream to speed their journey.

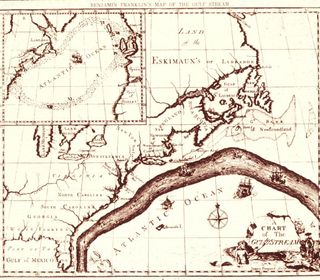

In his role as deputy postmaster of the British American colonies, Benjamin Franklin had a keen interest in the North Atlantic Ocean circulation patterns as a way to streamline communication between the colonies and England.

During a 1768 visit to England, Franklin discovered that it took British packets several weeks longer to reach New York from England than it took an average American merchant ship to reach Newport, Rhode Island. Franklin’s cousin Timothy Folger, a Nantucket whaling captain, explained that merchant ships routinely crossed the then-unnamed Gulf Stream while the mail packet captains ran against it. The merchant ships tracked whale behavior, measurement of the water's temperature and the speed of bubbles on its surface and changes in the water's color to follow the speedier route.

Franklin worked with Folger and other experienced ship captains to chart the Gulf Stream and giving it the name by which it is still known today.

Franklin's Gulf Stream chart was published in 1770 in England — where it was ignored — and subsequent versions were printed in France in 1778 and the United States in 1786.

It was years before the British finally took Franklin's advice on navigating the current but once they did, they were able to shave two weeks off the sailing time between Europe and the United States.

Climate change concerns

Like many aspects of the environment, the Gulf Stream has been affected by global warming, and research indicates that the core of the Gulf Stream moved 125 miles north in 2011.

Some scientists are concerned that melting glaciers will send cold water into the current and disrupt the Gulf Stream's flow. There is a possibility that without the warmth delivered by the Gulf Stream, Northern Europe could enter a new ice age.

— Kim Ann Zimmermann, LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kim Ann Zimmermann is a contributor to Live Science and sister site Space.com, writing mainly evergreen reference articles that provide background on myriad scientific topics, from astronauts to climate, and from culture to medicine. Her work can also be found in Business News Daily and KM World. She holds a bachelor’s degree in communications from Glassboro State College (now known as Rowan University) in New Jersey.