Antarctica Glacier's Retreat 'Unprecedented'

Like a plug in a leaky dam, little Pine Island Glacier holds back part of the massive West Antarctic Ice Sheet, whose thinning ice is contributing to sea level rise.

In recent decades, Pine Island Glacier's rapid retreat raised fears that the glacier could "collapse," freeing the ice sheet it buffers to flow even more rapidly into the southern seas. The West Antarctic Ice contributes 0.15 to 0.30 millimeters per year to sea level rise.

The big question is whether the hasty retreat is a recent change, caused by climate change, or a more long-term phenomenon.

"We need to know if what we observe today is something that started perhaps at the end of the last Ice Age or something that started in more recent times," said Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand, a marine geologist with the British Antarctic Survey.

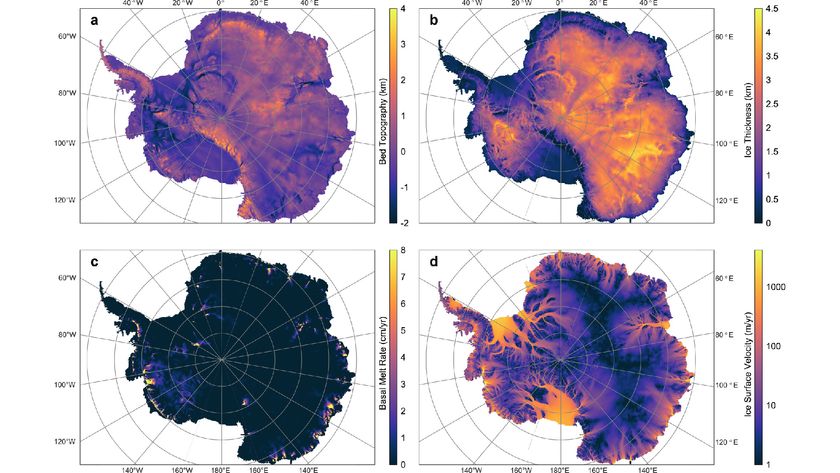

Pine Island Glacier's small ice shelf, a platform of ice floating on the ocean's surface, acts as a plug, holding the rest of the ice stream in place on land. As warm ocean currents melt the ice shelf from below, inland glaciers flow down to the coast and feed the thinning ice shelf. Changes to Antarctic wind currents, driven by global warming, have pushed relatively warmer ocean waters beneath the ice shelves.

In the past 20 years, Pine Island Glacier's grounding line, the location where the glacier leaves bedrock and meets the ocean, has retreated at a rate of more than 1 kilometer a year. The glacier itself has thinned at a rate of 5 feet (1.5 meters) a year since the 1990s, and its flow rate has accelerated by 30 percent in the past 10 years.

Pine Island Glacier only stretches 45 miles (40 km) across where it meets the ocean, but it drains an area of 62,665 square miles (162,300 square km).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To determine why Pine Island Glacier and its nearby cousin, Thwaites Glacier, are changing so rapidly, the British Antarctic Survey looked to the past. They studied sediments from Pine Island Bay, where the ice shelves stick tongues into the ocean.

Microfossils in mud retrieved by ocean drilling aboard a research ship pinpoint when and were ice covered the bay. This is because the microscopic marine life is only present if the ice shelf is absent. Radiocarbon dating of the fossils gave researchers a 10,000-year history of the past location of the ice.

"For the first time, we can put these modern observations of fast grounding-line retreat in a long-term context," Hillenbrand told OurAmazingPlanet.

"We can show that the present grounding-line retreat is really exceptional over a longer time scale, over the last 10,000 years," he said. "In the previous 10,000 years, the grounding line retreated by just about 90 kilometers [56 miles], but in the last 20 years, it retreated by 25 kilometers [15 miles]."

The results appear in the January 2013 issue of the journal Geology.

Hillenbrand and his colleagues also discovered there could have been three or four episodes of rapid retreat in the past 10,000 years, but these were short-lived, lasting just 25 to 30 years. Researchers found no evidence the glaciers had advanced in the past 10,000 years.

"Some say the fast grounding-line retreat will stop in a few years, others in a few decades. Others say that this retreat will actually continue and may lead to the complete collapse of the Pine Island Glacier drainage system," Hillenbrand said. "What we know is that, on the basis of this data, the current retreat is unprecedented."

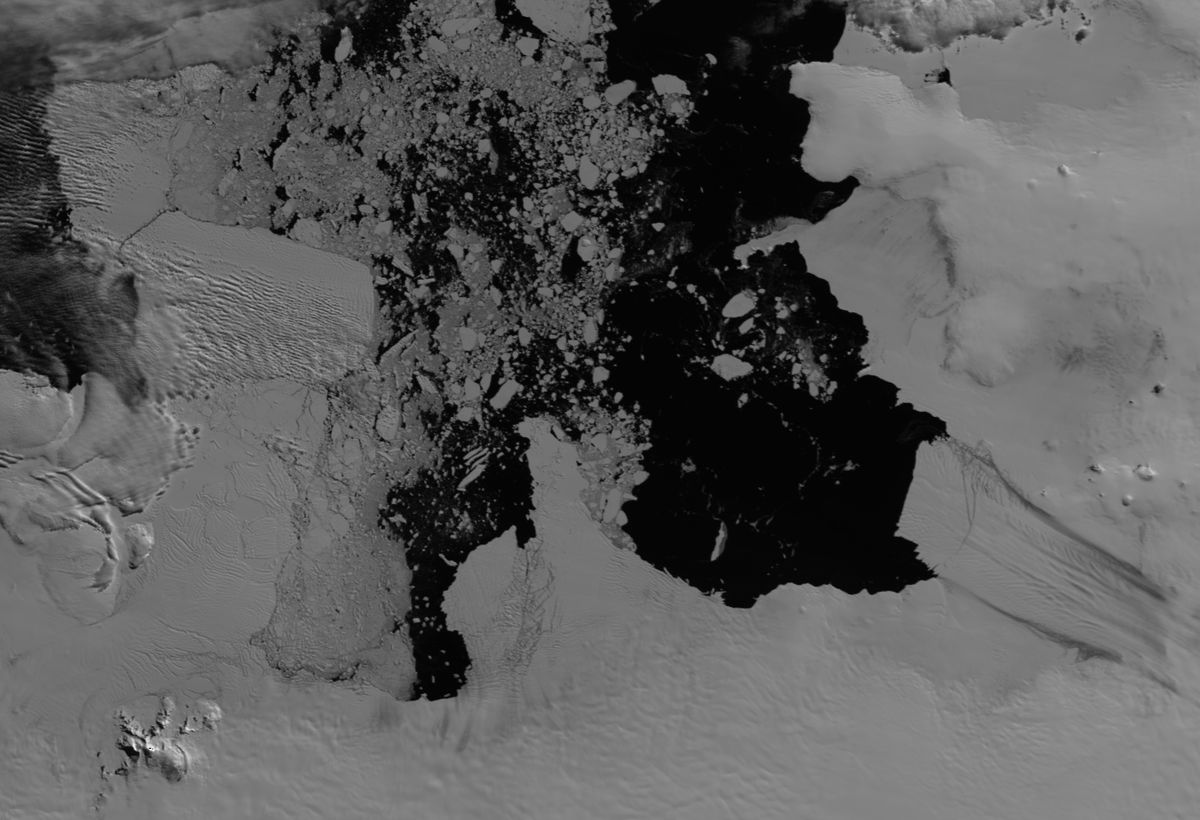

As Pine Island Glacier retreats, it drops huge icebergs. In 2011, NASA's Operation IceBridge discovered a giant crack crossing the ice shelf. (The IceBridge expedition tracks yearly changes in the Antarctic ice.) The fissure, about 20 to 25 km inland from the edge of the ice shelf, could birth an iceberg the size of New York City.

IceBridge scientists say the calving is part of the natural process by which glaciers flow to the sea. The last calving event (the sudden release of ice) let loose in an iceberg that measured 26 by 11 miles (42 km by 17 km) in 2001. The Pine Island Glacier seems to generate big bergs on a decade-long cycle, scientist say. [Photo Album: Antarctica, Iceberg Maker]

The British team now plans to investigate what's driving the thinning of the glaciers in Pine Island Bay. "We're pretty sure the most important driver is warm ocean water, but this is still an open question," Hillenbrand said.

"Now that we have this retreat history, we can study the past dynamic behavior of these glaciers, so we can predict better the future behavior of these ice streams and their contribution to future sea level rise."

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.