Physicists Measure The Real Age of Skin

(ISNS) -- If you feel tempted to lie about your age, you'd better steer clear of a process developed by a team of Taiwanese scientists.

The laser-based technique, called harmonic generation microscopy, or HGM, measures the natural age of individuals' skin by comparing the sizes of two different types of skin cell.

The process, also known as a "virtual biopsy," gives dermatologists the first standardized means of measuring the extent of age damage in skin -- and potentially in other body parts.

"No one has ever seen through a person's skin to determine his or her age," said project leader Chi-Kuang Sun, head of the Molecular Imaging Center at National Taiwan University. "Our finding serves as a potential index for skin age."

The patented method offers a way to diagnose and monitor the progress of skin diseases and to study skin damage from exposure to the sun. It also promises a means of measuring the effectiveness of anti-aging skin products.

"This is a very reasonable approach," said Barbara Gilchrest, professor of dermatology at Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center. "There is a huge medical need for a device like this."

According to Rosemarie Osborne, research fellow at P&G Beauty, the method is effective because it links cellular, or histological, changes with the appearance of skin.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It also has the advantage of working in real time. "A lot of histologic work in the past used frozen skin tissues," Osborne said. "This method looks at skin in real time – a more realistic view."

Team member Yi-Hua Liao, a dermatologist at the National Taiwan University Hospital and College of Medicine noted several medical benefits of the method.

"HGM is similar to skin biopsies for disease diagnosis, but unlike skin biopsies it is non-invasive," Liao said, adding that physicians can use the method to "follow up the efficacy of cosmetic products" by evaluating collagen fibers due to aging or the melanin content in a pigmented spot.

The method is not restricted to studying the age of skin.

"HGM can be applied to a variety of organ systems, and skin is one of the easily approached organs," Sun said.

The method relies on the generation of "harmonics" of laser light shone on the skin. Just like musical harmonics, these are vibrations at two, three and more times the frequency of the original light that occur when the light interacts with cells in different skin layers.

The researchers fired a brief burst of infrared laser light at the skin of volunteers' inner forearms. The light penetrated a little more than one-hundredth of an inch, reaching the depth at which the upper skin layer, the epidermis, meets the lower layer, the dermis.

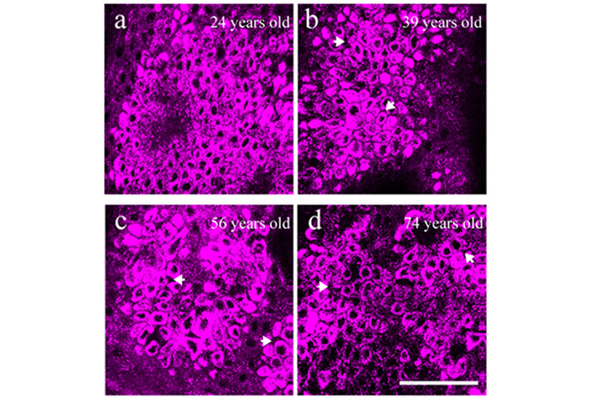

Using sophisticated microscopes to detect the second and third harmonics produced when the light reacted with components of the skin, the team created high-resolution 3-D maps of skin cells and structures inside them.

The maps showed that natural aging, free of sun exposure, significantly increases the size of basal keratinocytes, the most common cells in the skin's outermost layer, and their nuclei. However, the sizes of other skin cells, such as granular cells, do not increase with age.

Hence, the team concluded, the relative changes in the sizes of the two types of cell could serve as an index of the natural aging of skin caused by intrinsic factors, such as programmed development and genetics.

Sun and his team applied the technology to the inner part of patients' forearms to ensure that they measured only the skin's natural age, free of any effects caused by exposure to the sun and other environmental hazards.

"This is an area of the human body seldom exposed to the sun, and is suitable to study intrinsic skin aging," Sun explained. "We can also examine skin over buttocks. But, it would be inconvenient for the subjects."

The potential application of the technique to evaluate anti-aging treatments coincides with and complements several strains of research by the cosmetic industry.

"There's a lot of interest in these methods," Osborne said. "We do a lot of work to evaluate the clinical benefits of new products."

The volunteers who participated in the project were all Chinese. For other population groups, skin may react differently to extrinsic sources, owing to melanin content or other factors. However, Sun said, "There may be no differences in intrinsic aging between different races."

The team's advance indicates that the concept of inner beauty can apply to the skin as well as the persona. And while outer beauty may be skin deep, it's clear that what's under the skin provides the real giveaway to age.

The research was published last month in the journal Biomedical Optics Express.

A former science editor of Newsweek, Peter Gwynne is a freelance science writer based in Sandwich, Mass.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics.