Japan Tsunami Left Behind Huge Underwater Dunes

The giant earthquake that devastated Japan in 2011 reshaped the seafloor, forming unexpectedly large underwater dunes and possibly dramatically influencing Japan's marine ecosystem, researchers have found.

The new findings, detailed online Jan. 1 in the journal Marine Geology, hint that clues about past tsunamis could be found on the sea bottom.

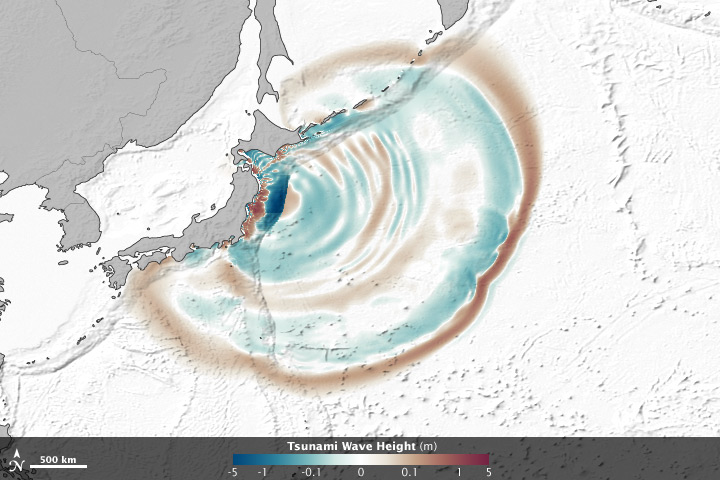

The magnitude-9.0 Tohoku-Oki temblor that struck in March 2011 was the most powerful earthquake to hit Japan in recorded history, strong enough to slightly alter the pull of gravity under Japan. It then set off a tsunami that lay waste to the coast of the northeastern part of the country, triggering a crisis at the nuclear power plant at Fukushima, a combination that may be the first "complex megadisaster" the world has ever seen.

Twenty days after the tsunami, researchers went out in ships with sonar rigs for a four-day emergency field survey to judge the impact of the tsunami on the seafloor and see whether large ships could safely come into Kesennuma Bay about 55 miles (90 kilometers) northeast of the city of Sendai. The inner bay is usually calm, and is used as a port of refuge during typhoons. The maximum height the tsunami reached — a towering 66 feet (20 meters) — was seen west of the bay.

"Originally, this survey was not purely a scientific one, but was conducted to support tsunami-affected peoples," said researcher Kazuhisa Goto, a geologist at Tohoku University in Japan. "There were many floating pieces of debris, and we still had a threat of tsunami generation by aftershocks."

Research had revealed the tsunami had dramatic effects on Japan's coast, but it remained uncertain whether tsunamis in general could affect much deeper areas of the seafloor — for instance, by creating deep underwater dunes. [7 Craziest Ways Japan's Earthquake Affected Earth]

Now Goto and his colleagues find the 2011 tsunami did in fact generate large underwater dunes, the first direct evidence that tsunamis can rework sea bottom sediments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We hadn't expected the presence of such dunes," Goto told OurAmazingPlanet.

Tsunami deposits

The researchers scanned areas of the sandy, silty seafloor about 30 to 50 feet (10 to 15 m) deep. They found dunes up to 65 feet (20 m) long and 6 feet (1.8 m) high. No dunes were seen in the area in surveys of the seafloor before the 2011 tsunami.

"On land, thicknesses of the tsunami's deposits were usually only about 30 centimeters [12 inches], but on the shallow sea bottom, it was meter-scale," Goto said.

It remains difficult to say how many dunes the tsunami might have created.

"The tsunami wave current was very strong and I would not be surprised if dunes were formed across the entire bay, plus slightly deeper areas, but some of them may have been erased since then by normal post-tsunami wave activity," Goto said.

The fact that the tsunami drastically altered conditions on the seafloor should affect Japan's marine ecosystem. "Future monitoring of the marine ecosystem is highly required," Goto said.

Past tsunami evidence

These findings also suggest that geological evidence of past tsunamis may be well-preserved on the seafloor, helping shed light on how often an area might experience tsunamis in the future, and how powerful those killer waves might be.

Usually scientists look for such evidence on land, but in urban areas, such traces are often destroyed as people reshape the earth there, making it difficult to see what tsunami risks those cities might face, Goto explained.

"We may try to drill deeper in the dune field to find geological evidence of past tsunamis," Goto said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.