Panda Boot Camp Teaches Cubs Survival Skills

Panda cubs have the cuteness thing down pat, but rough-and-tumble? Not so much. Now scientists are hoping to teach the roly-poly bears survival skills they'll need for living in the wild.

The new mission is partly the result of a panda cub being released into the wild without the proper training. Xiang Xiang, a male cub, was released into Wolong Nature Reserve, located high in the mountains of western China's Sichuan Province, in April 2006. Unfortunately, Xiang Xiang wasn't prepared for the harsh reality of the wild. After less than a year of wandering the mountains, the cub was killed by neighboring males during turf wars.

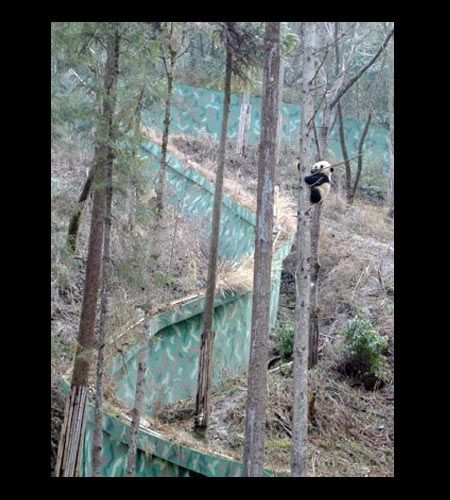

Enter Tao Tao, a 2-year-old male panda currently roaming in Lipingzi Nature Reserve in southwestern China. The cub went through a boot camp of sorts, and now scientists are monitoring the furball with GPS.

Hemin Zhang, director of the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda in Wolong, and his colleagues realized after Xiang Xiang's death that panda upbringing is critical.

And the best time to teach a panda new tricks seems to be during the cub years, so Zhang's team, including Jianguo "Jack" Liu of Michigan State University, taught momma pandas how to relay crucial survival skills — foraging and avoiding predators — to their cubs. [Baby Panda Pics: See a Cub Growing Up]

"Our people cannot teach a panda to live in the wild," Zhang said in a statement. "Now we leave the teaching to the momma." The momma panda and the humans who monitor the animals are the only individuals with access to the cubs. Even the human keepers must go undercover, wearing panda suits when interacting with the cubs.

The scarcity of human exposure keeps the pandas fearful of humans, a caution that will help the cubs survive in the wild, Zhang said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, cubs are kept on their tiptoes by reminders of predators, which come in the form of recordings of vocalizations and scat spread around the enclosure from clouded leopards and other hungry threats. The reserve is also home to some non-threatening species, such as pheasants, sheep and pigs.

So far, the scientists say, Tao Tao is doing fine, though they warn that the real test will come in the spring, or mating season. During this season of love, Zhang said, competition between males can turn lethal.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.