Timbuktu: History of Fabled Center of Learning

Timbuktu is a city in Mali, in West Africa, that was founded 1,800 years ago. During Europe’s Middle Ages, it was home to a rich writing tradition that saw the creation of millions of manuscripts, hundreds of thousands of which survive to present day.

'From here to Timbuktu'

In the West, the city has become synonymous with mysterious isolation, the farthest one can travel. However, for centuries this was a major trading hub and a center for scholarship. The city reached its height in the 16th century when it was controlled by the Songhay Empire. “[I]t has been estimated that Timbuktu had perhaps as many as 25,000 students, amounting to a quarter of the city’s population,” write John Hunwick and Alida Jay Boye in the book "The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu" (Thames and Hudson, 2008).

An Islamic city, with three large mosques, the study of the Koran formed the bedrock of this learning tradition with its scholars composing, copying and importing works on many subjects including astronomy, mathematics, law, geography and what we would think of as history. Researchers in a BBC documentary even note the survival of a 500-year-old recipe for toothpaste.

In late 2012 Timbuktu came under attack from extremist groups that had come to power in the north of Mali.

“Radical Islamist rebels in northern Mali have repeatedly attacked the fabled city’s heritage, taking pickaxes to the tombs of local saints and smashing down a door in a 15th-century mosque,” writes Geoffrey York, a reporter for Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper, in a recent article filed from Mali.

He notes that in addition to the architectural destruction the city’s libraries, full of manuscripts, are under threat. “Some experts consider them as significant as the Dead Sea Scrolls — and an implicit rebuke to the harsh narrow views of the Islamist radicals.”

Where is Timbuktu?

Timbuktu is in the West African nation of Mali on the southern edge of the Sahara. The city is situated 12 miles (20 kilometers) north of the Niger River. In 2009, it had a population of about 54,000.

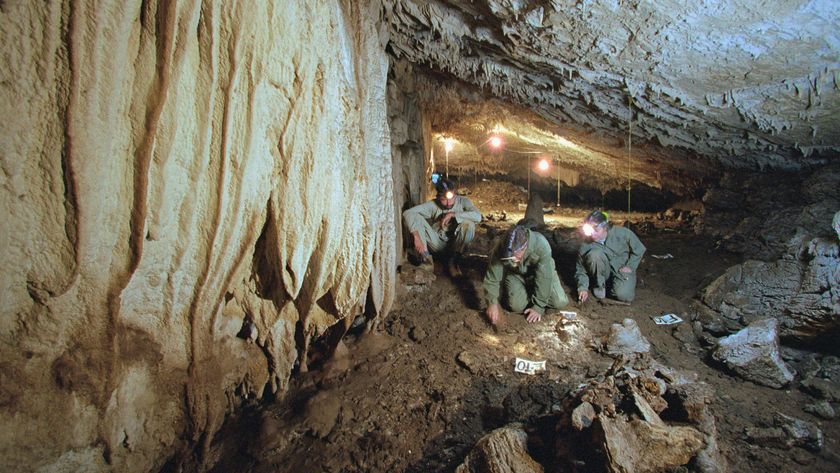

Historical records indicate that the city was founded at least as early as A.D. 1100 with archaeological work, carried out before extremists took over, suggesting that Timbuktu may have even earlier origins.

“Evidence from the excavations suggest that permanent large-scale urban settlements at Timbuktu may have developed as early as A.D. 200, with initial occupation dating back to the Late Stone Age,” writes Douglas Park, an archaeologist with Yale University who conducted work in Timbuktu in 2008, in the Newsletter of the West African Research Association and the West African Research Center.

He notes that this early city had strong ties with “proto-Berber tribes” from the eastern Sahara. “There are also pieces of evidence that shows that Timbuktu became part of the trans-Saharan trade by A.D. 600, as evidenced by North African-style glass beads and copper found in burials in Timbuktu.”

As Timbuktu entered the historic period this trade picked up with gold, coming from the south, passing through the city in preparation for its transport north across the Sahara to North Africa.

“The most important item exchanged for the gold was rock salt,” write Hunwick and Boye, who note that the 14th-century Arabic historian al-Umari claimed that people in West Africa “will exchange a cup of salt for a cup of gold dust,” an exaggeration, probably, but the type of story that lured later European explorers.

Great mosques

Three large mosques were constructed at Timbuktu and have become some of the most iconic monuments in the city. The sticks seen on the sides of the buildings serve not only an aesthetic purpose, but also as scaffolding for re-plastering the surface of the monuments.

Researchers Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair write in the "Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture" (Oxford University Press, 2009) that around A.D. 1325, after the ruler of the Malian Empire (which at the time controlled Timbuktu) returned from a gold-laden pilgrimage to Mecca, construction of the Djingueré Ber (also known as the “Great Mosque”) was undertaken in the southwestern part of the city. The efforts were led by the poet and architect Abu Ishaq al-Saheli. It was then reconstructed in the 16th century and altered again in the 19th.

“Built of mud-brick and stone rubble, with the ends of beams projecting out of the fabric of the building, the mosque has squat, conical corner towers, a minaret c. 16 m [50 feet] high, a flat roof supported on arcades of mud piers and several vaulted limestone arches,” Bloom and Blair write.

Another mosque called Sankoré was built in the northern part of the city and became a center for scholarship. “[T]he interior walls of which conform to the exterior dimensions of the Ka῾ba at Mecca” write Bloom and Blair, the Ka’ba being a cube-shaped shrine that is the holiest place on Earth for Muslims.

The area of the city where the Sankoré mosque is located, known as the Sankoré quarter, became associated with learning. “The Sankoré quarter attracted many scholars to live, study and teach, thus gaining a reputation for higher learning,” write Hunwick and Boye.

Another mosque known as Sidi Yahyia was built in the center of the city in the 15th century, write Bloom and Blair. It too was later restored and was “reconstructed in stone by the French in the 20th century.”

Center of learning

While gold was Timbuktu’s most frequent export, one of its most important imports was said to be books.“In Timbuktu there are numerous judges, scholars and priests, all well paid by the king, who greatly honours learned men. Many manuscript books coming from Barbary are sold. Such sales are more profitable than any other goods,” wrote Leo Africanus in the 16th century. (Translation by John Hunwick)

Although mosques like Sankoré were centers of learning, much of the day-to-day teaching activity occurred more informally in the homes of scholars, write Hunwick and Boye. “The core of the Islamic teaching tradition is the receiving of a text, which is handed down through a chain of transmitters or silsila from the teacher to the student, preferably through the shortest and most prestigious set of intermediaries,” they write. The student would listen to the teacher’s dictation, write their own copy and read it back, or listen to another student read it. “When he had a correct copy he could then study the meaning of the text and its technical intricacies through lectures delivered by his teacher and at a higher level by question and answer.” The scholars had their own private libraries to help them teach.

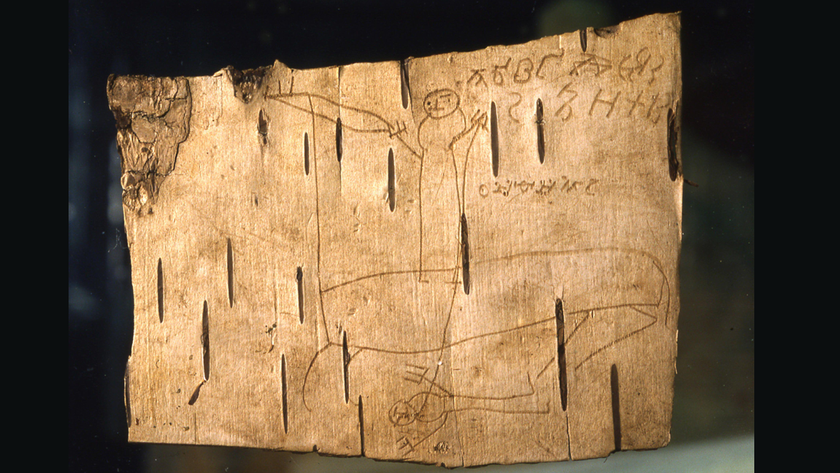

Researcher Abdel Kader Haidara notes that the surviving manuscripts are in a poor state, having fallen victim to termites, moisture and other problems associated with the passage of time. While today hundreds of thousands survive, originally there would have been many more. “If not for these things [damage] the estimated number of manuscripts in Timbuktu and its surrounding areas would have been in the millions,” he writes in a chapter of the book "The meanings of Timbuktu" (HRSC Press, 2008).

European exploration

The decline of Timbuktu as a hub for scholars began in 1591 when the site was taken over by musket-wielding soldiers from Morocco. Although further great works would be produced, including two great chronicles of Timbuktu’s history finished in the 17th century, the city struggled to regain its former lustre.

European explorers, lured by tales of gold, made great efforts to locate the city but it wasn’t until 1828 that French explorer René Caillié visited Timbuktu and returned alive. Later in the 19th century, the French built a colonial empire in much of West Africa. They ruled Timbuktu until 1960, when Mali regained its independence.

Before the recent takeover by extremist groups, local conservators, librarians and scholars were making progress in conserving and digitizing the city’s manuscripts.

These gains, and the manuscripts themselves, are now threatened. “I’m always asking myself thousands of questions about the manuscripts,” Mohamed Diagayete, a local scholar, told the Globe and Mail. “When we lose them, we have no other copy. It’s forever.”

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.