Alien Auroras May Light Up Exoplanet Night Skies

Scientists have kept a close watch on the dazzling northern lights on Earth and other planets in our solar system, but now they have the chance to explore the auroras of alien planets orbiting distant stars, a new study suggests.

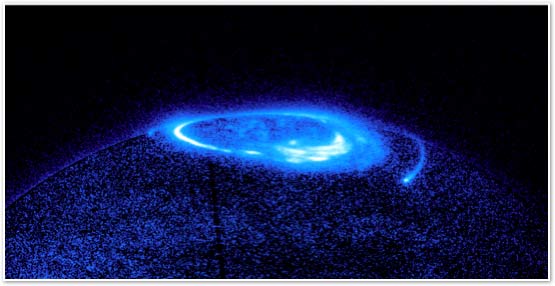

Auroras on Earth occur when charged particles from the sun are funneled to the planet's poles and interact with the upper atmosphere, sparking spectacular light shows. Similar processes have been observed on other planets in the solar system, with Jupiter's auroras more than 100 times brighter than those on Earth, scientists said.

Now, scientists are finding evidence of aurora displays on exoplanets for the first time. Researchers used the Low-Frequency Array radio telescope based in The Netherlands to observe radio emissions most likely caused by powerful auroras from planets outside of our solar system.

"These results strongly suggest that auroras do occur on bodies outside our solar system, and the auroral radio emissions are powerful enough — 100,000 times brighter than Jupiter's — to be detectable across interstellar distances," study lead author Jonathan Nichols, of the University of Leicester in England, said in a statement.

Jupiter's auroras are caused by an interaction of charged particles shot from its volcanic moon, Io and the rotation of the planet itself. The gas giant turns on its axis once every 10 hours, dragging its magnetic field along for the ride, and effectively creating a whirl of electricity at each of the planet's poles.

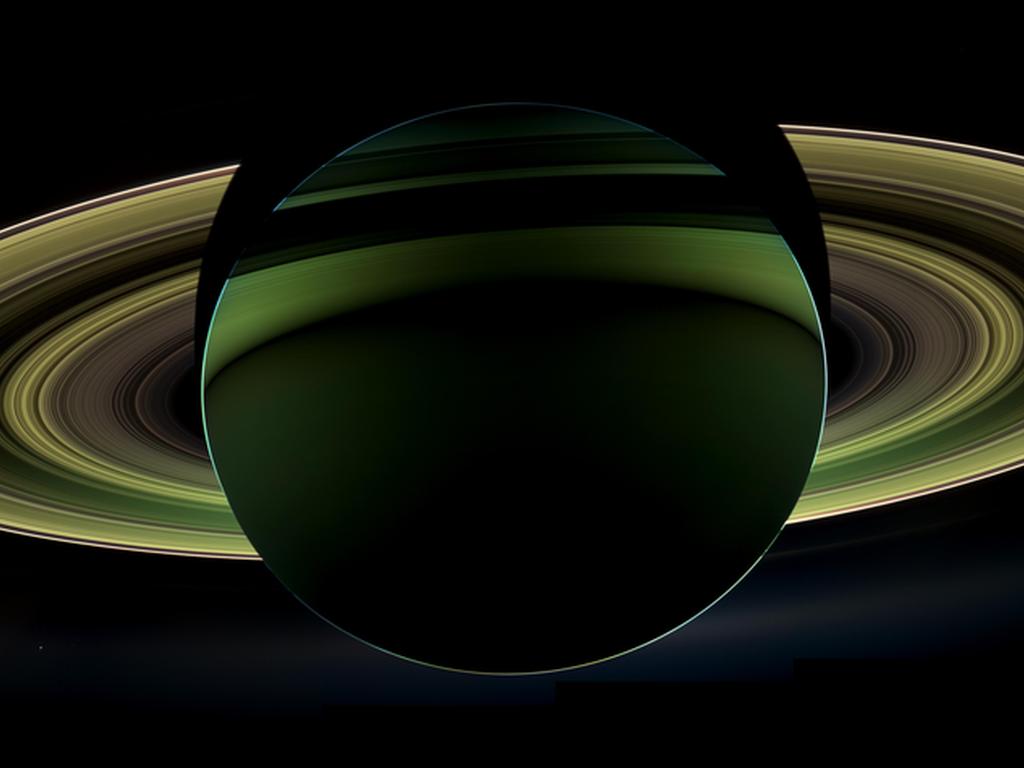

Auroras akin to Earth's have been spotted on Saturn. But these newest findings show that auroras on exoplanets probably aren't formed from charged particles travelling on the solar wind. Instead, the auroras on the dim, "ultracool dwarf" stars and "failed stars" known as brown dwarfs that Nichols studied probably behave more like Jupiter's northern and southern lights.

By studying these radio emissions, scientists will gain more insight into the strength of a planet's magnetic field, how it interacts with its parent star, whether it has any moons and even the length of its day.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new research is detailed in a recent issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter @mirikramer or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.