Crop circles: Myth, theories and history

Crop circles are really no mystery. These expansive forms of landscape art are made by people.

Crop circles are a very straightforward phenomenon: They are a type of landscape art made by humans.

Despite evidence to the contrary, some people remain convinced that crop circles were made by aliens brought by UFOs.

But how did unidentified flying objects come to be linked with flattened expanses of cereal grains? And why have these designs historically been associated with southern England?

The answer to all of these questions is simple: Doug Bower and Dave Chorley.

Bower and Chorley were a pair of friends who lived near Winchester, England. In 1978, the two were sitting in a pub, "wondering what we could do for a bit of a laugh," Chorley told TIME magazine in 1991. Inspired by earlier reports of UFO landings — the UFO craze was well underway in the late 1970s, having gathered steam after a retired Air Force officer gave an interview about the Roswell incident, claiming that something extraterrestrial had crashed in the New Mexico desert in 1947 — Bower and Chorley decided to create their own faux UFO landing site.

Arming themselves with some boards, rope and a twist of wire stuck to a baseball hat brim for siting their patterns, Bower and Chorley headed into a field and started creating a masterpiece. No one noticed. In fact, the two had to make multiple forays into the southern English countryside over several years before their newly invented crop circles were noticed by the global media. Once the story went global, and UFO enthusiasts began to show up in droves, the artists came forward and admitted their hoax.

Related: Top conspiracy theories

Since then, crop circles have become both a landscape art form and a tourist attraction. Their cachet as extraterrestrial artifacts is no longer as strong as it once was, though true believers, nicknamed "croppies," still think aliens are responsible for at least some crop circles. These days, marketers are a more likely culprit — crop circles have been used to advertise the Olympics and computer chips.

What are crop circles?

Crop circles are large-scale patterns made by flattening crops such as wheat, barley or canola. Crop circle artists still use boards of wood to stomp out patterns, as a National Geographic documentary filmed in 2004 illustrated. The artists hide their tracks in existing tractor-tire ruts, making it seem as if the design dropped out of the sky.

Crop circles can be simple circles or more complex patterns. Southern England remains a hotspot for crop circle artists, with masterpieces incorporating triangles, spinner shapes and crescents. They've also popped up elsewhere around the world, with one article in the Illinois newspaper Courier & Press calling them a "plague" in the state in the 1990s. ("We think it's probably just kids," Rock Island County Sheriff Tod VanWolvelaere told the paper decades later.)

Sometimes, "crop circles" appear for apparently natural reasons. The crop circles that Chorley and Bower took their inspiration from were found in Australia in 1966, though they weren't actually crops; they were patches of flattened, floating reeds in a lagoon in far north Queensland. The farmer who found them claimed to have seen a flying saucer whizzing away, but locals said such circles were common during the wet season. According to the Cairns Post, the most likely explanations were downdrafts of wind or small vortices known as willy-willies (similar to dust devils).

Famous crop circles

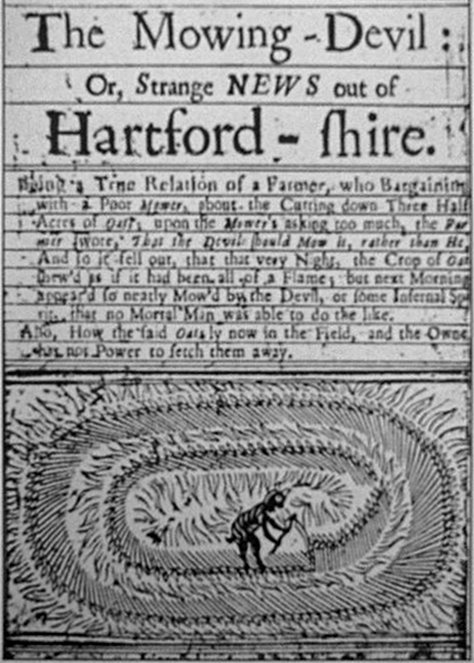

The first report of a crop-related mystery now linked to crop circles was a woodcut chapbook, or small book containing ballads and poems and tracts, called "The Mowing Devil," dating back to 1678. According to Oxford Reference, this chapbook tells the tale of a cheap farmer who refused to pay a laborer to cut his oats. Overnight, the devil did the job instead, "cutting them in round circles." Though the oats of the story were mowed, not flattened, crop circle believers used this fable to bolster their case for crop circles' long-ago roots.

In 1996, a famous crop circle known as the "Julia set" appeared near Stonehenge. A local pilot claimed that he flew over the field an hour before the crop circle appeared and saw nothing, and then flew over it again, only to see a spiral of progressively larger circles, according to the Skeptical Inquirer. This supposed sudden appearance raised excitement that the crop circle had to be of paranormal origin. But according to the Skeptical Inquirer, these eyewitness accounts were sketchy — and a local crop-circle creator claimed to know who made the Julia set and that it had been done the night before the crop circle was spotted, not during broad daylight.

Perhaps the cutest crop circles to make international news were simple ones spotted in Tasmania's legally grown opium field in 2009. The opium is grown for the pharmaceutical industry, which uses the plants to make drugs such as morphine. According to the Australian state's attorney general, wallabies were getting into the fields and hopping in circles after eating the opium poppies and "getting high as a kite," NBC News reported that year. The disoriented wallabies were stomping on the poppies, causing crushed circular patches.

Additional resources

Crop circles are human-made, but they're still visually stunning. Smithsonian Magazine's The Art of the Crop Circle delves into the history and artistic merit of these structures. National Geographic's 2018 article "Inside the mystical world of crop circle tourism" looks at the travel spurred by crop circles. For documentation of southern England's crop circle art, the website Temporary Temples offers stunning aerial photos and context.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.