Space Junk Menace: How to Deal with Orbital Debris

The saga of what steps that must be taken to deal with the evolving threat of Earth-circling orbital debris is a work in progress. This menacing problem — and the possible cleanup solutions — is international in scope.

Space junk is an assortment of objects in Earth orbit that is a mix of everything from spent rocket stages, derelict satellites, chunks of busted up spacecraft to paint chips, springs and bolts. A satellite crash in February 2009, for example, marked the first accidental hypervelocity crash between two intact artificial satellites in Earth orbit. That cosmic crash created significant debris — a worrisome amount of leftover bits and pieces.

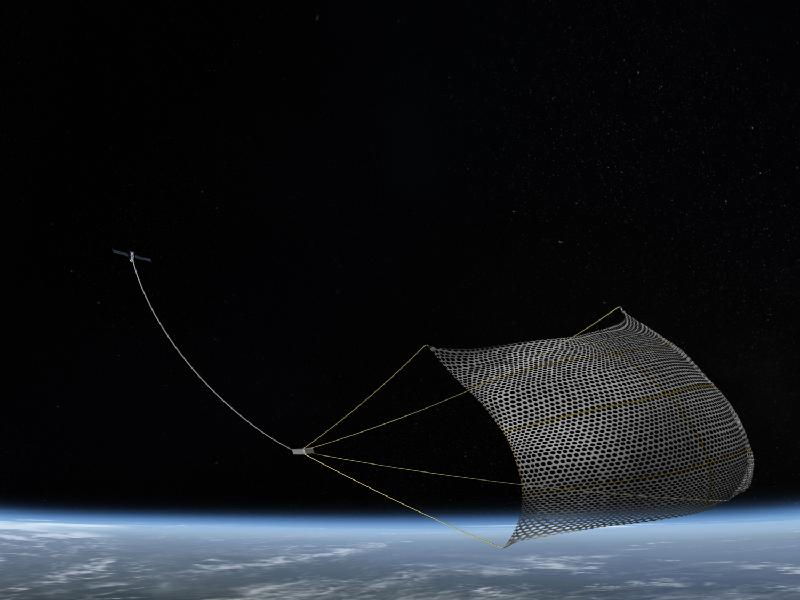

Against this backdrop of untidiness in space and the global worry among spacefaring countries it causes, experts continue to tackle the issue of exactly what to do about orbital debris. A number of rules have been pondered to address the space debris problem, from regulations that attempt to cut down on the shedding of new debris to better tracking of the human-made refuge, as well as scavenging concepts including fishing nets, lasers and garbage scows.

But how to best characterize the orbital debris dilemma, and its future, also stirs up debate and heated dialogue.

Point of no return

The clutter in Earth orbit is a situation that will continue to worsen, according to Marshall Kaplan, founder and principal of Launchspace in Bethesda, Md.

"The problem is that we've already fallen off that cliff," Kaplan told SPACE.com. "That's the reality of it and people don't want to admit that reality." [Photos of Space Junk & Cleanup Ideas]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spending millions of dollars to retrieve space junk isn't effective, Kaplan said.

Now, ways to better track and identify space debris are being devised. Low-Earth orbit is where the main problem is — from roughly 435 miles (700 kilometers) to about 745 miles (1,200 km), he said.

"It's a serious, serious challenge," Kaplan said. "This is not a U.S. problem … it's everybody's problem. And most of the people that produced the debris, the serious offenders, like Russia, China, and the United States, are not going to spend that kind of money. It's just not a good investment." While the creation of orbiting junk continues rise with each rocket launch, there is no market for tackling the issue directly, Kaplan said.

"We've reached the point of no return. The debris will continue to get worse in terms of collision threats … even if not another satellite were launched, the problem will continue to get worse," he added.

Speeding debris crashes

Kaplan said the frequency of collisions between active satellites and debris pieces is going to increase.

The real question, Kaplan said, is not what everyone is going to do about debris. Rather, the true question is what needs to be done about active satellites in harm's way of speeding riffraff.

"My prediction is that we are going to evacuate the areas of high debris density. It's just too dangerous to operate there. We're going to need to reinvent how we use space," Kaplan said. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

In the case of large national security satellite assets, one option may be to distribute smaller satellites in lower altitudes, Kaplan added. These multiple layers of spacecraft would collectively create virtual products, such as imagery and other intelligence data. The users of this information would receive the same kind of data, but from a different satellite constellation, he said.

As one step toward that future, Kaplan is working with multiple universities to help establish new research centers on space debris and a next-generation national security space architecture.

Environmental stability

Darren McKnight, technical director for Integrity Applications Incorporated, headquartered in Chantilly, Va., suggested that the current debate on active debris removal and the evolution of the debris environment is still developing.

McKnight said that, currently, policymakers and engineers examine environmental stability, preventing the cascading of derelict collisions from increasing exponentially over the next century. This scenario, known as the "Kessler Syndrome," is the primary metric to judge how many derelicts need to be removed and when they should be removed.

The Kessler Syndrome is one in which the density of objects in low Earth orbit is high enough that collisions between objects could cause a cascade. Each collision generates space debris, which increases the likelihood of further collisions. [Solar Sails Could Sweep Up Space Junk (Video)]

"The overall issue is that as we continue to consider active debris removal options, I question whether or not environment stability is the only metric to be tracking," McKnight told SPACE.com.

Lethal space debris

McKnight, along with company colleague Frank Di Pentino, propose that the probability of satellite failure from impact from non-trackable, yet lethal debris fragments — in the 5 millimeter to 10 centimeter size range — is a more appropriate metric. The reason is because it directly reflects harmful effects of space debris on space operations. Furthermore, these effects are likely to occur much sooner than observable manifestations of the cascading effect.

McKnight and Di Pentino's research suggests that any mitigation scheme, be it just-in-time collision avoidance, active debris removal or other methods, cannot rely on a model that does not account for projected add rates, new launches on other factors. They contend that collision rate is “not a sufficient metric” for assessing operational risk.

Wanted: A long-term plan

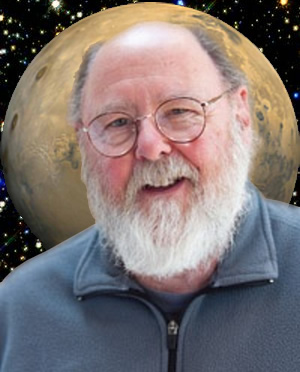

There is much work to do regarding orbital debris, said Donald Kessler, chair of the 2011 National Research Council (NRC) report "Limiting Future Collision Risk to Spacecraft: An Assessment of NASA's Meteoroid and Orbital Debris Programs." He is a retired head of NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office and is a space debris and meteoroid consultant in Asheville, N.C.

Kessler said that the NRC committee that produced the report strongly felt that what was missing from the programs was a long-term strategic plan — one that outlined a path that eventually determines how manage future space operations in a way that preserves the environment.

"However, this is not simply a NASA issue … it is an international issue, and will require a carefully coordinated effort," Kessler said.

Can the space junk problem be solved?

NASA and the international community, Kessler said, "have already done enough research to know that the environment will continue to get worse if we continue on the same path … the only environmental issue to be resolved is how quickly the environment in various regions deteriorates."

The international community, through the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), has been very active in understanding the current environmental trends, sharing information and establishing internationally recognized mitigation requirements.

However, Kessler said that current mitigation practices are insufficient, even with 100 percent compliance. Missing in action is a plan to determine what do about the predicted worsening space environment, he said — that is, how to stop or reverse the trend of increased debris resulting from increased collisions.

Sustainable environment

Kessler added that the fundamental issues to be resolved are:

- How do we minimize the possibility of future high-velocity collisions between spacecraft and upper stage rockets?

- If we cannot eliminate that prospect, how do we clean up after a collision?

"Removal from orbit, collision avoidance, satellite servicing and repair, satellite recycling in orbit, debris storage locations, change to using a 'stable plane' at higher altitudes especially in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) … are all possibilities," Kessler added. "Some are mutually exclusive and may not be appropriate at all altitudes, while others could combine to be more effective."

Still to be sorted out is what type of legal structure might be needed in order to implement any plan, Kessler said.

"I believe it is time that the international community takes a serious look at the future of space operations," Kessler said. "There's need to begin a process to answer these questions and determine which path will most effectively provide a sustainable environment for spacecraft in Earth orbit."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.