Tiwanaku: Pre-Incan Civilization in the Andes

Located in Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, the ancient city of Tiwanaku was built almost 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) above sea level, making it one of the highest urban centers ever constructed.

Surrounded, in large part, by mountains and hills, the city reached its peak between roughly A.D. 500 and A.D. 1000, growing to encompass an area of more than two square miles (six square kilometers), organized in a grid plan. Only a small portion of the city has been excavated. Population estimates vary but at its peak Tiwanaku appears to have had at least 10,000 people living in it.

Although its inhabitants didn’t develop a writing system, and its ancient name is unknown, archaeological remains indicate that the city’s cultural and political influence was felt across the southern Andes stretching into modern-day Peru, Chile and Argentina.

Today, with a modern-day town located nearby, Tiwanaku is a great ruin. “Massive, stone-faced earthen mounds rise from the plain; nearby are great rectangular platforms and sunken courts with beautiful cut-stone masonry,” writes Denver Art Museum curator Margaret Young-Sánchez in her book "Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca" (University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

Origins

It isn’t known when settlement at Tiwanaku began, but Young-Sánchez notes in her book that people in the Lake Titicaca area started settling permanently around 4,000 years ago.

She notes that by this time llamas (used as pack animals), alpacas (prized for their fur) and camelids had all been domesticated. In addition “farmers learned to cultivate hardy, frost-resistant crops like tubers and quinoa, watered by natural rainfall and water channeled from the mountain slopes,” Young-Sánchez writes. A millennium later these adaptations had been enhanced by “raised-field agriculture” a technique which “involves creating artificially raised planting mounds separated by canals of water.”

These adaptations enabled the development of larger and more complex settlements, one of which, Tiwanaku, would come to dominate the region.

“Why Tiwanaku? To varying degrees, environmental shift, changing trade routes, competitive political practices, and a vibrant ritual cult each played a role,” writes Vanderbilt University professor John Wayne Janusek in his book "Ancient Tiwanaku" (Cambridge University Press, 2008). “Ongoing research suggests that Tiwanaku’s rise and initial expansion were grounded more profoundly in consensus and cultural affiliation than coercion or militarism.”

The city

Field Museum researcher Patrick Ryan Williams and members of his team note in a 2007 journal article that archaeological excavations reveal that the people of Tiwanaku “maintained a dense urban population residing in well-defined, spatially segregated neighborhoods, or barrios, bounded by massive adobe compound walls.”

These “residential neighborhoods were characterized by multiple clusters of domestic structures (e.g., kitchens, sleeping quarters, storage facilities), some of which were apparently organized around a small private patio,” they add, with the inhabitants of these clusters appearing to have had “access to larger, shared outdoor plaza areas utilized for communal ceremonial events.”

The researchers are careful to add that no residential neighborhood at Tiwanaku has been completely excavated or mapped. However, one area that archaeologists have explored considerably is the city center, which contains a number of monumental structures. It’s an area, Young-Sánchez writes, “which was surrounded by an artificial moat ...”

Sunken Temple and Kalasasaya

The area surrounded by the moat contains a number of structures that appear to be of religious importance.

Janusek writes that the earliest structure appears to be the “Sunken Temple,” a small building that is descended to by way of a staircase on the south. After descending the stairs, stone monoliths can be seen in the center of the room. They depict “what were most likely the more ancient and powerful mythical ancestors of the collective communities.”

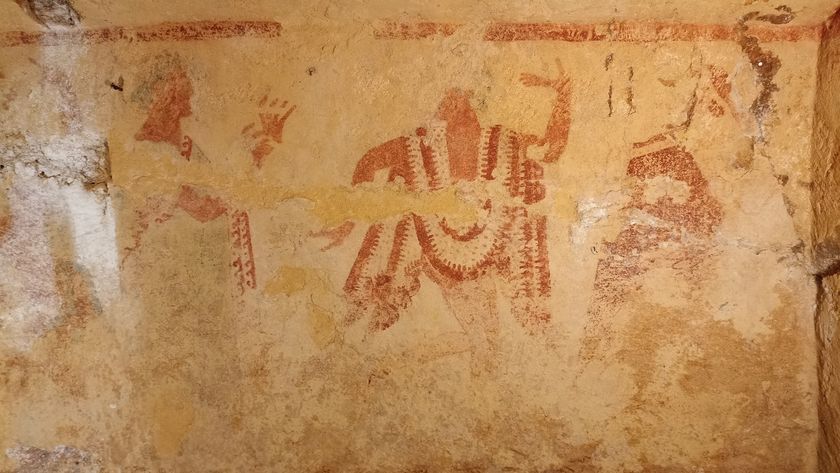

In addition, the walls of the sunken temple were decorated with the images of “deity-like beings with impassive faces and elaborate headdresses,” Janusek writes, adding that others “appear to represent skulls with desiccated skin and sunken eye sockets, and still others appear to be wailing phantasms like the banshees of Irish lore.”

Researchers Brian Bauer and Charles Stanish note that the Sunken Temple is square and about 27 meters (89 feet) long on each side. (From the book "Ritual and Pilgrimage in the Ancient Andes: The Islands of the Sun and the Moon," University of Texas Press, 2001).

Adjacent to the Sunken Temple is a platform complex known as the “Kalasasaya,” which Bauer and Stanish writes measures 120 meters by 130 meters (393 feet by 427 feet).

Janusek notes that this platform was gradually expanded and modified over time and was built over an earlier residential complex. “In building the Kalasasaya over this residence, which may have been home to some of Tiwanaku’s high-status founders, those in charge sought to position themselves as legitimate inheritors of Tiwanaku’s early ritual prestige.”

Akapana

Also in the area surrounded by the moat was what Bauer and Stanish call an “artificial pyramid” known at the Akapana. “This monumental construction measured approximately 200 by 250 meters (656 feet by 820 feet) at its base and was more than 16.5 meters (54 feet) high,” they write, noting that it had six stone terraces.

“The Akapana was by far the largest construction at Tiwanaku and was most certainly one of the principal political and sacred areas of the capital.”

University of Chicago professor Alan Kolata writes in a chapter of Young-Sánchez’s book that when archaeologists excavated the northwest portion of the pyramid they came across the skeletons of 21 people, who may be from groups Tiwanaku conquered. Found with llama bones and polychrome ceramics “several of the skeletons bore evidence of deep cut marks and compression fractures that could only have been produced by forceful blows,” Kolata writes, this hacking could have taken place before or shortly after death.

“Speaking less delicately, these people had been literally hacked apart with a heavy blade before being buried at the base of the temple.”

Pumapunku

Outside of the moat area, and located to the southwest, is a massive, unfinished, platform known as the Pumapunku. “The main platform was extensive, measuring over a half-kilometer (over 1600 feet) east-west and consisting of superimposed terraces that were roughly T-shape in plan,” writes Janusek in his book.

The main entranceway was on the west side. “One moved up the stairway through stone portals, some covered with lintels carved as totora reed bundles and into a narrow, walled, passage” Janusek writes. This passage then led to an “inner courtyard” with a “sunken paved patio.”

Janusek notes that water seems to have played a central role in the rites that took place on the platform. The Choquepacha spring is located southwest of the structure with stone conduits built around it indicating “the remains of an elaborate construction.”

Decline and rebirth

Around A.D. 1000, Tiwanaku fell into decline and the city was eventually abandoned. It collapsed around the same time the Wari culture, based to the west in Peru, also fell. The timing has led scientists to wonder whether environmental change in the Andes played a role in felling both civilizations.

But while Tiwanaku became abandoned, its memory lived on in the mythology of the people of the Andes.

“Even after its abandonment, Tiwanaku continued to be an important religious site for the local people,” writes UCLA archaeologist Alexei Vranich in an online "Archaeology" magazine article. It later became incorporated into Inca mythology as the birthplace of mankind, Vranich writes, and the Inca built their own structures alongside the ruins.

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Related:

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.