Oldest Spider Crabs Discovered in Fossil Reef

The remains of eight new species of crustaceans, including the oldest known spider crabs that lived 100 million years ago, have been uncovered in a fossil reef in northern Spain, scientists report.

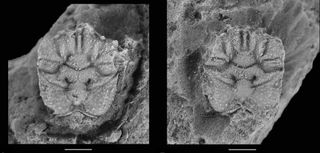

The fossils were found in the abandoned Koskobilo quarry alongside other species of decapod crustaceans (a group that includes crabs, shrimp and lobsters). The two oldest-known spider crabs, named Cretamaja granulata and Koskobilius postangustus, are much older than the previous record holder, said study author Adiël Klompmaker, a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida.

"The previous oldest one was from France and is some millions of years younger," Klompmaker told LiveScience, referring to the spider crabs. "So this discovery in Spain in quite impressive and pushes back the origin of spider crabs as known from fossils."

C. granulatawas about 0.6 inches (15 millimeters) long and showed distinctive features to suggest it was a spider crab, including two diverging spines coming out of its rostrum (the extended portion of the carapace, or shell, in front of the eyes) and a somewhat pear-shaped carapace. The fossil spider crab also sported spines on its sides at the front of the body. [See Photos of the Ancient Spider Crabs]

The reef where they were found seems to have vanished shortly after these creatures lived. "Something must have happened in the environment that caused reefs in the area to vanish, and with it, probably many of the decapods that were living in these reefs," Klompmaker said. "Not many decapods are known from the time after the reefs disappeared in the area," added Klompmaker, who details the findings in a forthcoming issue of the journal Cretaceous Research.

With a team of researchers from the United States, the Netherlands and Spain, Klompmaker collected fossils in the Koskobilo quarry in 2008, 2009 and 2010.

"We went there in 2008, and in the first two hours found two new species," Klompmaker said in a statement. "That's quite amazing — it just doesn't happen every day."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With the new findings, some 36 decapod species are known to have existed at the abandoned quarry, making it one of the most diverse localities for decapods during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), Klompmaker said.

The researchers also found there were more diverse ancient decapods living within the reefs — where they fed, mated and sought shelter — than in other parts of the ocean.

"One of the main results of this research is that decapod crustaceans are really abundant in reefs in the Cretaceous," Klompmaker wrote in an email. "The presence of corals seemed to promote decapod biodiversity as early as 100 million years ago and may have served as nurseries for speciation."

Last year, Klompmaker reported finding fossils of tiny lobsters huddled together in the seashell of an extinct mollusk known as an ammonoid. The "embracing" lobsters, found in a rock quarry in southern Germany, suggested these fearsome-looking crustaceans were sociable as long ago as 180 million years, when the little crustaceans lived.

"This is the oldest example of gregarious behavior for lobsters in the fossil record — and not just lobsters but the entire group of decapods, which includes lobsters, crabs and shrimp," Klompmaker, who was at Kent State University, said at the time. "What this tells us is that this type of behavior of grouping together may have been very beneficial early on in the evolution of these crustaceans."

Klompmaker was also part of a team that discovered a new hermit crab at the same quarry, naming it after Michael Jackson (Mesoparapylocheles michaeljacksoni), as it was found around the time the singer died.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.