In Photos: Mammals Through Time

Cute Mammal

The 160-million-year-old fossil of an extinct rodentlike creature, now called Rugosodon eurasiaticus, from China is helping to explain how multituberculates — the most evolutionarily successful and long-lived mammalian lineage in the fossil record — achieved their dominance.

Like most early nocturnal mammals, R. eurasiaticus was active at night. This reconstruction shows Rugosodon searching for food among ferns and cycads on the lakeshores in the darkness.

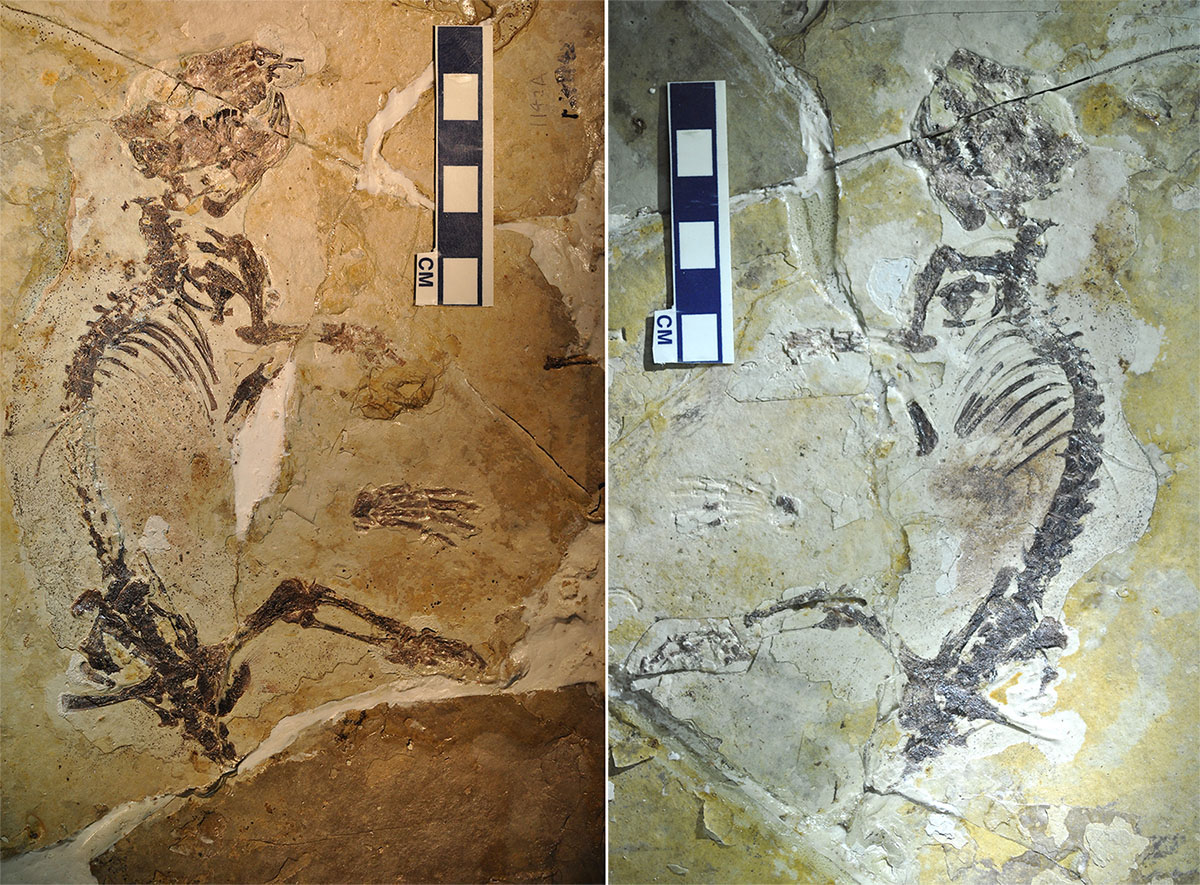

Cute Mammal Fossil

The fossil of Rugosodon eurasiaticus is preserved in two shale slabs in part (left) and counterpart (right). It is about 6.5 inches (17 cm) long from head to rump, and is estimated to have weighed about 2.8 ounces (80 grams). The sediments at the site of discovery are lake sediments with embedded volcanic layers. The fossil assemblage of Rugosodon also includes feathered dinosaur Anchiornis and the pterosaur Darwinopterus. By the dental features, Rugosodon eurasiaticus closely resembles the teeth of some multituberculate mammals of the Late Jurassic of the Western Europe, suggesting that Europe and Asia had extensive mammal faunal inter-changes in the Jurassic.

Furry Mammal Mama

An artist's rendering of the hypothetical placental ancestor, a small, insect-eating animal with a long, furry tail. The research team reconstructed the anatomy of the animal by mapping traits onto the evolutionary tree most strongly supported by the combined phenomic (physical traits you can see) and genomic data and comparing the features in placental mammals with those seen in their closest relatives.

Multituberculates

Some of the world's earliest mammals were the multituberculates, a group of small rodentlike animals that first emerged on Earth about 165 million years ago. For the next 80 million years, they stayed small, seeming to evolve slowly while living in a limited number of habitats and eating insects.

Here, an artist's conception depicts a multituberculate in its natural habitat at the time of the dinosaurs.

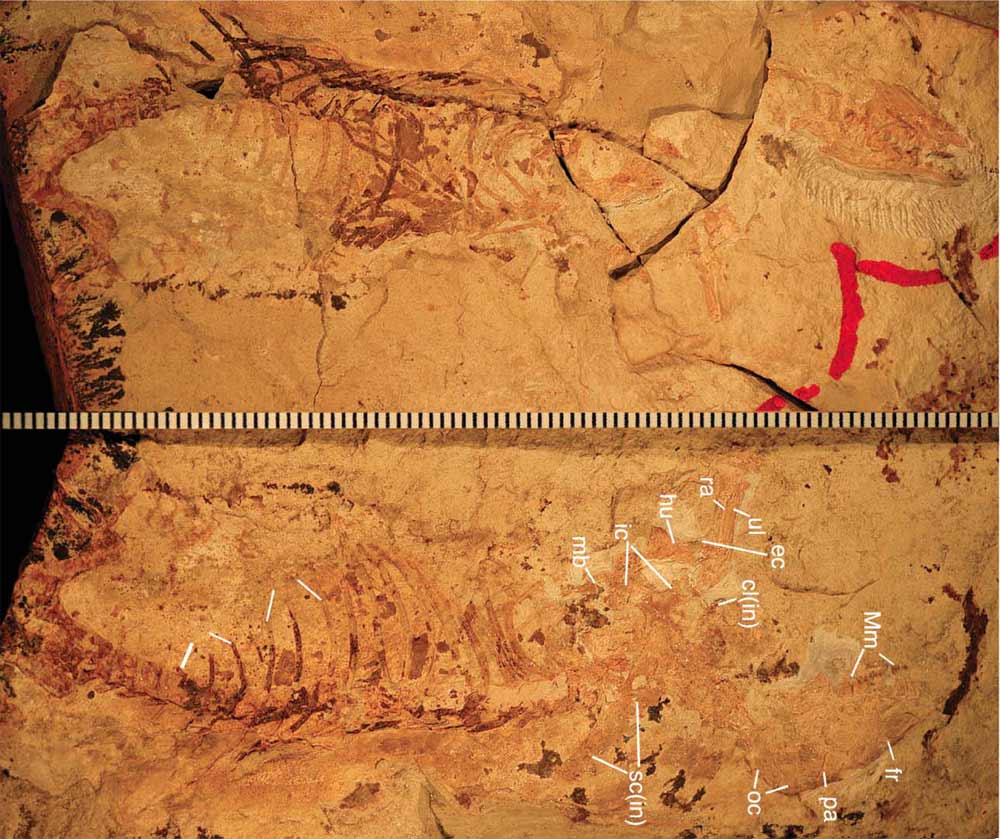

Power Digger

Dubbed Pseudotribos robustus, this ancient mammal (its bones shown here) was discovered in 165 million-year-old lakebeds corresponding to the Jurassic Period in Northern China. It measured about 5 inches (12 centimeters) in length and weighed between 20 to 30 grams (.04 to .07 pounds). The animal, which resembled a small opossum, likely fed on worms and insects and lived above ground, although it had strong limbs and would have been capable of "power digging," scientists say.

Mongolian Mammal

First excavated in Mongolia in the 1970s, this mammalian fossil sat in storage for decades until researchers for the Russian Academy of Sciences rediscovered and analyzed it, reporting their results in 2012 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

What they found was a dog-size, strong-shouldered digger called Ernanodon. This mammal lived about 57 million years ago, after dinosaurs had died out and our furry ancestors had taken over. Ernanodon was known from one other fossil found in China, but that specimen is warped, and some archaeologists even thought it might be a fake. Shown here, a close relative, the modern-day pangolin (top) and the ancient Ernanodon antelios (bottom).

Ancient Shrew?

A shrewlike animal (shown here in an artist's depiction) that snagged insects from ferns lining the shores of freshwater lakes 160 million years ago, might be one of the first "true" mammals to walk the Earth, back when the dinosaurs roamed.

The fossil, discovered in what is now Liaoning Province in China, is the oldest evidence of the divergence of these "true" or placental mammals from their marsupial counterparts, and indicates the mammalian lineage was evolving faster than expected during the Jurassic Period.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Missing Link?

The remains of an ancient mammal named Zhangheotherium quinquecuspidens were discovered in the Jianshangou Valley in northeastern China. Analysis of the fossil remains suggested the tiny creature, which lived during the age of dinosaurs, shared features with both modern mammals and their reptilian relatives.

For instance, like reptiles, the mammal's legs would have splayed out; it possessed a tiny spur on its rear feet that would've ejected venom, similar to egg-laying mammals called monotrenes; and its inner ear bone showed features that were more modern than the most primitive animals but not as advanced as modern mammals.

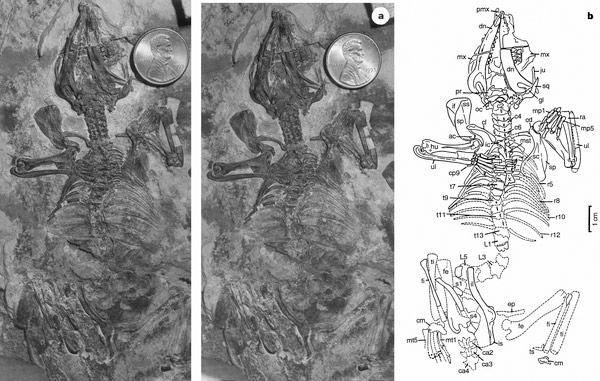

Gobi Mammal

This shrew-sized Cretaceous-age animal, Ukhaatherium nessovi, which was uncovered in 1994 in the Gobi Desert by the Mongolian Academy and the American Museum of Natural History, is one of the many mammals used in the recent mammal tree-of-life study. When it was discovered, the remarkably well-preserved skeleton of this small creature showed the presence of epipubic bones, attached to both sides of the pubis. In living mammals, these bones occur only in marsupials (mammals like kangaroos that often develop their young in pouches) and monotremes (mammals like platypuses, which lay eggs). But their presence in Ukhaatherium nessovi showed that a close relative of recent placental mammals that lived many millions of years ago also had these bones.

Squirrelly forest

Here, a reconstruction of arboreal mammals in a Jurassic forest. The three animals on the left side represent three newfound species of euharamiyidan mammals that lived some 160 million years ago. The other two represent a gliding species and another euharamiyidan, respectively, that were reported earlier. The new findings on the three extinct squirrel-like mammals, published in the Sept. 11, 2014, issue of the journal Nature, suggest their closest known relatives were the rodent-like multituberculates. [Read full story]

Jurassic Mammal

A newfound extinct mammal species, now named Xianshou songae and shown in this reconstruction, was a mouse-sized tree dweller in the Jurassic forests. The mammal, described in the Sept. 11, 2014, issue of the journal Nature, belonged to an extinct group of Mesozoic mammals called Euharamiyida. [Read full story]

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.