Climate Change May Make Flu Seasons Worse

(ISNS) -- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, influenza continues to be widespread in 38 states. Since this season's severe epidemic started earlier than expected, many people who wanted to get a vaccination may not have received one before the outbreak began.

According to research done at Arizona State University in Tempe, there are hints that climate change may be a factor in the flu season's early timing.

Using data going back to 1997, Sherry Towers and her colleagues found that warm winters are usually followed by severe and early flu outbreaks. Last winter was one of the warmest on record; the current flu season is one of the worst, with an unusually high number of cases, a much more serious strain of influenza virus (H3N2), and an early onset. The results were published in PLOS Currents: Influenza.

Whether that is true outside of the U.S., or outside the world's temperate zone, is still up in the air.

The researchers' curiosity was piqued when flu came much earlier this season than it usually does, Towers said, and seemed severer. Using CDC data, the researchers found a pattern: warm winters were usually followed by heavy flu seasons.

"During warm winters, flu is less transmittable," Towers said. "Fewer people catch it." That applies to both primary flu varieties. That leaves a higher percentage of the population without immunity the next season.

Fewer people also get vaccinated. The presence of the disease is less visible, and the effects are less obvious, Towers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In an average year, vaccinations are received by only about 40 percent of Americans, mostly those in advanced years.

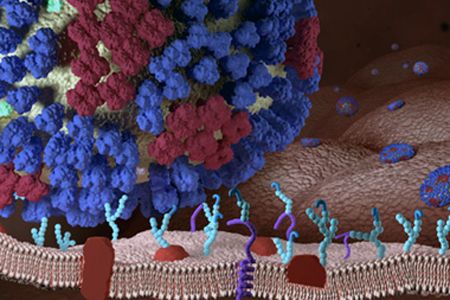

Flu is highly contagious, even more so than many researchers suspected. In a paper published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Werner Bischoff at Wake Forest University in Winston Salem, N.C., reported that flu patients in hospitals were capable of spreading the viruses six feet from their heads without sneezing or coughing. All they have to do is breathe or talk.

According to the CDC, 59 children have died of influenza-related disorders such as pneumonia this flu season as of January 26. More than 7,200 adults have been hospitalized with confirmed flu cases, half of them over the age of 65. No one is sure how many adults died because states are not required to report flu-related deaths to the CDC. For a typical year, estimates range from 23,000 to 48,000, according to the New York State Department of Health.

It takes about two weeks for the body to fully respond to the flu vaccine and develop the antibodies needed to fight off an invading virus. Scientists believe the vaccine is less effective in the elderly than the young

The vaccine loses its ability to protect against the virus in several months, so getting a flu shot this year will not be of help in gaining immunity for upcoming years. Additionally, the virus comes in various strains and each year CDC guesses which three strains are likely to be most common and those three are worked into the vaccine. They guessed correctly in 18 of the last 22 flu seasons. The virus is constantly mutating, so even an effective vaccine this year would most likely be ineffective the next.

Weathering Influenza

Temperature and humidity play a role in outbreaks, Towers said.

When the U.S. experiences a mild winter, the Arizona researchers found "on average 72 percent of the time the next epidemic was severer than average, with epidemic growth rate 40 percent higher than average, and a peak coming 11 days earlier than average." There was an 80 percent chance it would erupt before the end of the year.

If the climate is warming, Towers said, flu outbreaks could get worse.

"Our results … suggest that expedited manufacture and distribution of influenza vaccines after mild winters has the potential to mitigate the severity of future influenza epidemics," the researchers wrote.

Wilbur Chen, assistant professor at the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland's School of Medicine in Baltimore, said while what Tower and her colleagues found may be true of the temperate zones, influenza does not appear to be seasonal in tropical zones, where temperatures are warm and less varied.

With funding from the Bill and Melissa Gates Foundation, the University of Maryland's program has been running an experiment in the central African nation of Mali, where the flu does not appear to be seasonal. There are some expansions of outbreaks in the two periods between wet and dry seasons, but temperature appears not to be a major factor.

"It is persistent all year around," Chen said. He added that he was uncertain that the Arizona State research would be applicable to outbreaks outside the United States.

Joel Shurkin is a freelance writer based in Baltimore. He is the author of nine books on science and the history of science, and has taught science journalism at Stanford University, UC Santa Cruz and the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics.

Most Popular