'Charioteer' Constellation Rides Through February's Skies

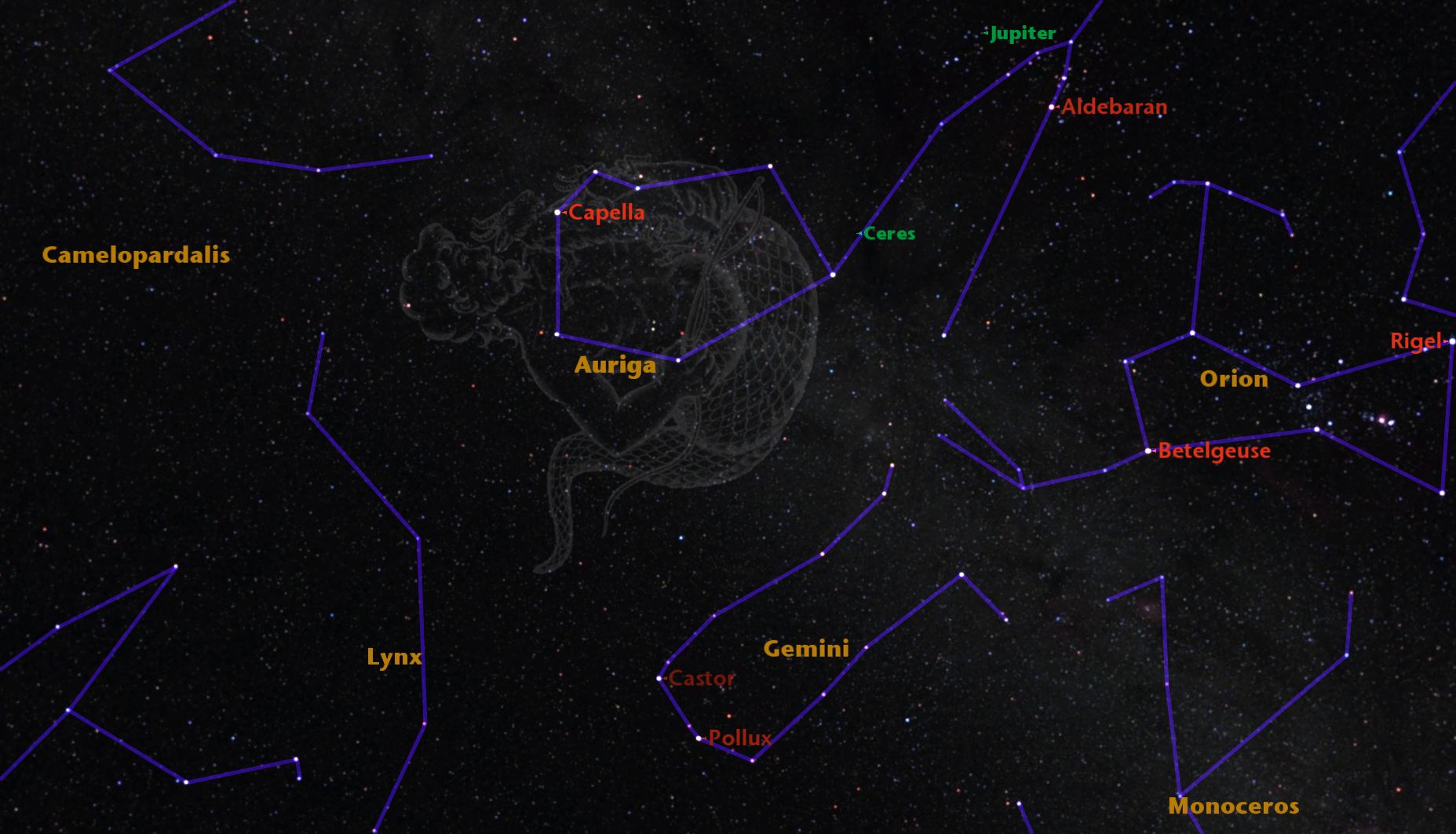

The celestial version of Ben Hur is wheeling a course high over our heads between 8 and 8:30 p.m. local time this week: Auriga, the Charioteer.

Depending how you look at Auriga, he can be visualized either as a kite or as a pentagon of five stars. The constellation's highlights include the golden-yellow star Capella, the second-brightest star currently above the horizon, and a row of three clusters of stars that are readily visible with only the slightest optical aid.

A Star Pattern to Get Your Goat

Capella is Latin for “she-goat,” for a rather unusual reason. Auriga is a constellation in which the old pictures and meanings of the star names have been hopelessly mixed from two antique conceptions.

According to the most ancient legend, Auriga was a goat herder and patron of shepherds and all who tend flocks. Yet the Greeks and Romans made him a famed trainer of horses and the inventor of the four-horse chariot. [Skywatching Events in February 2013]

The confusion in concepts is reflected in the ancient allegorical pictures and star names. Auriga is represented holding a whip in one hand in deference to the charioteer story, but in the other arm next to Capella are three tiny stars, known as The Kids. One of the Kids, Epsilon Aurigae, is a star apparently surrounded by a massive opaque disk of dust that every 27 years noticeably dims the star’s light, as it did just a couple of years ago.

In his classic guidebook, “The Stars: A New Way to See Them” (Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston), Hans A. Rey (1898-1977) drew Auriga as a tough-looking man with a jutting chin and a pug nose, ". . . as befits the driver of a war cart."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Capella is 16 times as wide as our sun and 174 times as luminous, and it's located 42 light-years away. Of all the bright first-magnitude stars, Capella is the nearest to the sky's north pole, and it's visible at some hour of the night throughout the year across much of the 48 contiguous United States.

Lying 46 degrees north of the celestial equator, Capella can pass directly overhead for anyone living at that latitude north of the terrestrial equator (say, Houlton, Maine or Geneva, Switzerland). And for anyone living at points north of latitude 44 degrees (for example, Minneapolis, Minn., or Bologna, Italy), Capella will appear to graze the northern horizon, but will not go below it.

It’s interesting to note that Capella is really a multiple-star system. A smaller star orbits just 70 million miles (113 million kilometers) from Capella, while two tiny companion stars orbit the main pair nearly 1 trillion miles (1.6 trillion km) away.

A scale model of this system would show the main pair as two globes 13 and 7 inches (33 and 18 centimeters) in diameter and 10 feet (3 meters) apart, while the two tiny companions would each be 0.7 inch (1.8 cm) in diameter, 420 feet (128 m) apart, and 21 miles (34 km) from the main pair!

Suburbs of the Milky Way

As noted earlier, the Auriga constellation can be visualized as a kite, but older star atlases show it attached to a second-magnitude star that goes by the name of El Nath, which actually officially belongs to the constellation Taurus (the Bull).

El Nath goes by the name Beta Tauri when it is considered as the tip of one of the Bull’s horns. Yet at one time it also went by Gamma Aurigae, marking the heel of the Charioteer.

With our evenings free of any bright moonlight this week, we can see the Milky Way spread across our sky. On a clear night, away from city lights, use binoculars to sweep along the entire Milky Way. The narrow winter Milky Way crosses the center of Auriga, making this whole region grand for binocular or telescopic sky sweeping. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy]

If we think as the Milky Way as an overview of our galaxy, during the winter we are looking out toward the suburbs of our own city of stars. "Downtown" would be looking toward Sagittarius. The direction diametrically opposite "downtown" is several degrees to the east of the star El Nath; we can call this part of the Milky Way "the suburbs."

While much of the excitement of exploring the Milky Way occurs in the summertime sky, we can see some remarkable objects in the winter as well, including several beautiful galactic star clusters within Auriga.

Three of these clusters — M36, M37, and M38 — look quite similar in binoculars, appearing as hazy gray glows lurking in a field rich with tiny stars. A more careful look, however, reveals differences among them.

M36 in the middle of the row is smaller and more concentrated than the other two. M37 and M38 are sized about equally, but M37 is brighter. All three clusters are roughly the same distance from the sun, in the range of 4,000 to 4,500 light years. Their estimated ages, however, differ widely, from 25 million years for M36 to 220 million for M38 and 300 million for M37.

Another binocular highlight nearby is a pattern known to some as the Leaping Minnow, a little group of 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars. (In astronomy, lower magnitudes signify relatively brighter objects. For comparison, Venus' magnitude is around -5.)

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tariq is the editor-in-chief of Live Science's sister site Space.com. He joined the team in 2001 as a staff writer, and later editor, focusing on human spaceflight, exploration and space science. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times, covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University.