Air Guns Give Glimpse Inside a Subduction Zone

Researchers are getting a closer look at what happens to a tectonic plate as it slides under another plate and enters the mantle, a process known as subduction.

New research at the Kuril Trench, a subduction zone off the eastern coast of Japan, shows that as one plate dives under another, the bottom plate fractures and allows a lot of seawater to seep in through cracks and faults.

That water is important because, like the water cycle between the atmosphere and the Earth's surface, the crust and mantle (the hot, flowing layer below the crust) have their own water cycle. Tectonic plates carry seawater into subduction zones, and, as a plate slides down into the mantle, the water is driven out. As it exits, the water can cause small earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, which bring the water (or rocks containing that water) back up to the crust.

The volume of water getting trapped in the subducting plate is likely enough to influence the water cycle at the Kuril subduction zone, said Gou Fujie, a seismologist at the Japan Agency for Marine – Earth Science and Technology, who led the study. 50 Amazing Facts About Earth]

Air guns at the Hokkaido rise

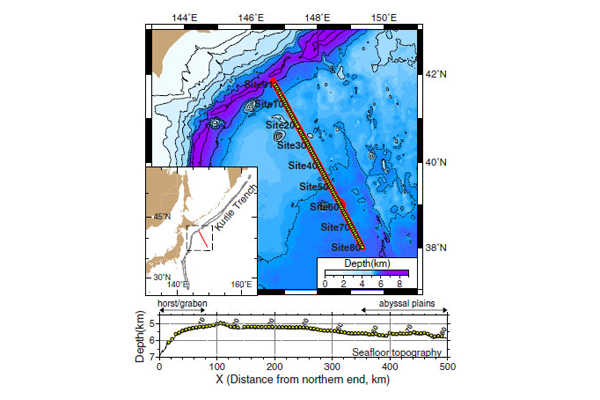

To study what happens as the Pacific Plate slides under the Okhotsk Plate in the Kuril Trench, Fujie's team looked at the outer rise region of the Pacific Plate, which is called the Hokkaido rise.

"The Hokkaido rise, the outer rise in the southern Kuril Trench, is one of the world's most prominent outer rise regions," Fujie told OurAmazingPlanet. "The outer rise is thought to be a result of plate bending just before its subduction."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To wrap your head around an outer rise, think of a piece of paper barely hanging off the edge of your desk. As you push down on the overhanging edge, part of the paper behind the edge of the desk pops up. That hump is similar to a tectonic plate's outer rise.

The team embedded a line of seismometers — 80 of them — in the Hokkaido rise. Then, sailing in a research vessel along the line of seismometers, Fujie fired a set of 32 air guns every 200 meters (about 650 feet). The seismometers recorded seismic waves from the shots of high-pressure air. Because seismic waves travel differently through different materials, Fujie's team could infer how much water the subducting Pacific Plate held at each point along the Hokkaido rise.

Water, water everywhere

The team found that the amount of water coincided with fractures in the plate — where there were more and deeper fractures, there was also more water. At the part of the Hokkaido rise nearest the Kuril Trench, faults and seawater likely reach down into the very bottom of the subducting Pacific Plate, and possibly into the mantle.

Scientists once thought that most water entered plates at midocean ridges, the boundaries between tectonic plates where new ocean crust is created and spreads out over ocean basins. But recent studies, including the one by Fujie's team, are showing that's not necessarily true.

"The amount of water penetrating the oceanic plate is larger in the outer rise region than in the mid-ocean ridge," Fujie said. "At the mid-ocean ridge, water circulation is generally restricted to shallower parts of the oceanic crust."

The study was published Jan. 16 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.