5 Reasons to Care About Friday's Asteroid Flyby

On Friday, an asteroid dubbed 2012 DA14 will whiz by Earth closer than any rock of its size since record-keeping began. But if NASA weren't aiming high-powered telescopes at 2012 DA14, most Earthlings would never know we'd been buzzed.

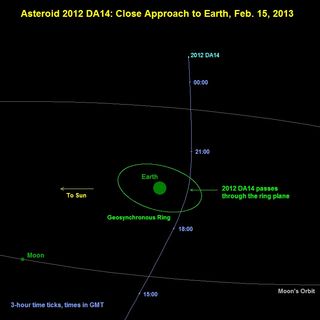

That's because the asteroid won't come any nearer than 17,150 miles (27,650 kilometers) away as it passes Earth. Still, 2012 DA14's lack of imminent threat to the planet is no reason to ignore the flyby.

From historical precedent to future implications, here's why you should care.

1. Asteroids are cool

Whether they fly by Earth or not, asteroids are important remnants of the early solar system. They formed early in the solar system's history, and their compositions may hint at why our neighbors are so diverse, from rocky Mars to gaseous Jupiter. That's one reason scientists are increasingly interested in probing the humble surfaces of asteroids. In 2007, NASA sent its Dawn spacecraft to the asteroid belt to visit Vesta and Ceres. Vesta is rocky and Ceres is icy, and the differences between the two could help explain what happened to differentiate the bodies in our solar system after they formed.

2. It's happened before

Friday's flyby is record-breaking; skywatchers have never before recorded an asteroid of this size passing so close to Earth. Unrecorded close calls are another story. In 1908, a hunk of space rock about 150 feet (45 meters) in diameter screamed into the atmosphere near the Tunguska River in Siberia. The asteroid or comet fragment — about the size of the White House — broke up explosively in the atmosphere, leveling more than 800 square miles (1,287 square kilometers) of forest. [The 10 Greatest Explosions Ever]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fortunately, the Tunguska Event happened in an extremely remote area, with the nearest human eyewitnesses miles away. But a rock like the one that caused the Tunguska Event, or like the one that will zip by Earth Friday, could level Washington D.C., and its suburbs, said Mark Boslough, a physicist at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, who has used computer modeling to recreate the Tunguska impact.

3. It will happen again

2012 DA14's flyby is a close one, but the asteroid itself is an old friend. Though first discovered in 2012, the space rock passes by Earth fairly frequently. It has an orbit around the sun roughly similar to Earth's, and zings by about twice per orbit. That means we'll be seeing 2012 DA14 again, although not as up-close. The next near-approach by the asteroid is scheduled for Feb. 15, 2046, according to NASA, when 2012 DA14 will pass about 995,000 miles (1.6 million km) from Earth. (Needless to say, astronomers have different ideas about "nearness" than most people.)

4. No, really — 2012 DA14 is one in (half) a million

Observing and measuring asteroids like 2012 DA14 is important because there are at least 500,000 of them out there. Less than 1 percent of these midsized near-Earth objects have been discovered, according to NASA.

Discoveries are made with optical telescopes, though once asteroids get close enough, scientists can use radar to better understand them. Astronomers of the La Sagra Sky Survey at the Astronomical Observatory of Mallorca in Spain discovered 2012 DA14 last February when the asteroid was 2.7 million miles (4.3 million km) from Earth.

Scientists at NASA's Near-Earth Object Program Office say that an asteroid the same size as 2012 DA14 approaches Earth this closely about every 40 years. Once every 1,200 years or so, one this size hits the planet. [See Photos of Asteroid 2012 DA14]

5. It helps us prepare

2012 DA14 won't hit Earth. But a close flyby like Friday's gives scientists the opportunity to think about what they'd do in the case of a once-in-a-thousand-year event, Sandia's Boslough told LiveScience.

For example, size estimates of asteroids are tentative until they reach radar range, Boslough said. Scientists would be able to pinpoint where an asteroid on a collision course with Earth would hit, but they wouldn't know with complete certainty how big it would be. Thus, evacuation orders might need to go out to larger areas than the best estimate of the size of the impact would suggest in order to be safe.

"For a lot of us, this is an opportunity to think about that, because we are going to have the answer when it does fly by," Boslough said of 2012 DA14. "What is the true size going to be relative to the estimates?"

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.