Proof! Mysterious Cosmic Rays Born in Star Explosions

![[Pin It] An artist's illustration of a supernova explosion,](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/DdEJkYD7iWjCyB6nktE8TG-1200-80.jpg)

After a century of mystery, scientists now have the first conclusive evidence that cosmic rays come from the violent aftermaths of exploding stars, researchers say.

Cosmic rays strike Earth from every direction in space with gargantuan amounts of energy,surpassing anything the most powerful atom smashers on Earth can produce. A wide variety of cosmic rays exist, from electrons to massive atomic nuclei to antimatter, but about 90 percent are protons.

Austrian scientist Victor Hess discovered these electrically charged particles from deep space after a high-altitude balloon flight in 1912. However, despite a century of research, the origins of cosmic rays had remained a mystery.

"Cosmic rays are a significant part of the total energy content of our galaxy, but so far we have had no incontrovertible evidence [of] where they come from," said study author Stefan Funk, an astrophysicist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University.

Cosmic ray mystery

Scientists have long suspected cosmic rays were linked to the aftermaths of supernovas, the most powerful exploding stars in the universe, which are visible at the farthest edges of the cosmos. Researchers speculated that cosmic rays are accelerated gradually and over long periods of time by the shells of gas that supernovas expel, known as supernova remnants.

However, since cosmic rays have electrical charges, they get deflected by any magnetic field they encounter. Since these rays likely careened around before reaching Earth, it's challenging to prove where they were born. [8 Baffling Mysteries of Astronomy]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

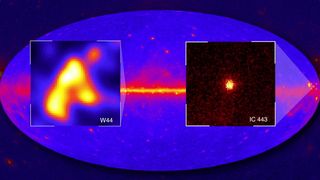

To help solve the mystery of cosmic ray nurseries, researchers spent four years analyzing gamma rays with the Large Area Telescope onboard NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The scientists focused on two supernova remnants, both located within the Milky Way: IC 433, which is about 5,000 light-years away in the constellation Gemini, and W44, which is about 10,000 light-years away in the constellation Aquila.

"We found, for the first time, sources in the universe that accelerate protons," Funk told SPACE.com.

Supernova clues

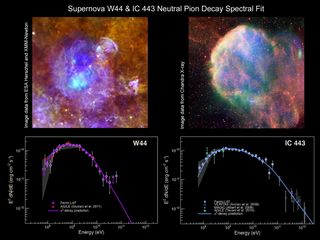

The shockwaves from supernovas can, in principle, accelerate protons to cosmic ray energies through a process known as Fermi acceleration. In this phenomenon, protons get trapped by magnetic fields in the fast-moving shock waves and accelerated to near the speed of light. Collisions among faster and slower protons can generate subatomic particles called neutral pions, which in turn quickly decay into gamma-ray photons, the most energetic form of light.

Unlike cosmic rays, gamma rays are not affected by magnetic fields, which means they zip out in straight lines and can be traced back to their sources. As such, the researchers looked for these gamma rays as direct evidence of cosmic ray creation.

The gamma rays from Fermi acceleration come in a distinctive range of energies. The data the scientists gathered from the supernova remnants matched the characteristic energy signature of neutral pion decay, clearly linking supernovas to cosmic rays.

"This is a 100-year old mystery and being able to see direct evidence of the accelerated protons felt great," Funk said.

"Until now, we had only theoretical calculations and common sense to guide us in the belief that cosmic rays were generated in supernova remnants," said astrophysicist Jerry Ostriker at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. "The direct detection of pion-decay signatures in supernova remnants closes the loop and provides dramatic observational evidence for a significant component of cosmic rays."

Although this research shows that supernovas can generate cosmic rays, it remains uncertain whether the star explosions cause most cosmic rays, or if there are other potentially more important sources for these particles, Funk said. It is also unclear how exactly supernova remnants accelerate protons, and up to what energies they can speed the particles.

"The acceleration in the shock wave is a rather slow process and happens over the lifetime of the supernova remnants," Funk said. "We would like to understand the efficiency of the acceleration in different evolutionary stages and other details of the process."

In future research, scientists could also hunt for the origins of cosmic rays of even higher energy than these protons. "To do so, one needs to use ground-based telescopes, instruments that use the interaction of gamma rays with the Earth atmosphere, such as HESS or VERITAS or the future Cherenkov Telescope Array," Funk said.

Ultra–high-energy cosmic rays, ones high both in mass and energy, "are extremely rare and therefore one needs huge detection areas," Funk added. "One such installation is the Pierre Auger Array in Argentina, and in the future people are talking about installing an instrument on the International Space Station that would look for interactions in the Earth atmosphere."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 15 issue of the journal Science, as well as at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston today (Feb. 14).

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.